![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Introduction

No matter what type of project is being considered at a Jewish burial site in western Ukraine, the most common first step to guide concepts, planning, and implementation is a preliminary assessment of the site, its setting, and its features. Some forms of assessment can be done remotely, for example via historical records and using imagery and data produced by other individuals or organizations, but to get a clear and multidimensional sense of the place with its memorial assets and challenges, the best approach is a “walkover survey”, i.e. to slowly walk the site and its environment, observing closely the setting and condition of natural and man-made features. Even after a project progresses in development, walkovers are important to occasionally assess the fit of concepts to the site, the success (or not) of preparatory work, ongoing changes to the landscape and built features, how burial site neighbors respond to the project, and how the project endures after completion. Seeing and studying the site first-hand, ideally in more than one season, can help to prevent serious mistakes and misunderstandings early in the project cycle.

A preliminary assessment will ideally consider sampling methods and resources from all of the possible phases of a broad cemetery preservation project, even if the initial project concept is much narrower, to ensure that remote concerns and influences are not overlooked. There is no separate references page for preliminary assessment on this website, because the assessment can and should exploit information resources from all of the guide phases. In an abbreviated assessment, the references related to site surveys and landscape planning are perhaps the most valuable, as they typically consider burial sites at the broadest scale.

The initial approach of some landscape design professionals to a potential project site can be very useful at this early stage. In the April 2019 edition of Landscape Architecture Magazine, Jacky Bowring writes that “[t]he French landscape architect Bernard Lassus exhorted a slow approach to a site. He spoke of the idea of ‘floating attention,’ and during the ‘course of long visits at different hours and in different weathers, to soak it up from the ground to the sky’. Bowring also quotes Marc Treib on the Swiss landscape architect Georges Descombes: “slowness is there at the stage of engaging with the site. In an age of phone cameras and time pressure, site visits can become rapid-fire digital assaults. Descombes draws. Drawing is a way of slowing down engagement, of looking carefully.” Treib further describes Descombes’ approach as “walking again and again around the site,” looking “out for things we normally do not see, such as flowers and mice… We didn’t know in advance what would interest us.” Bowring says “this early phase of slowness is key to the strategy of ‘mining and reassembling the past.'” [Jacky Bowring; The Antidote to Excess; p.156]

The outcome of these preliminary assessments should be a grounded sense of the cemetery or mass grave site and its role as a place of memory and heritage in modern western Ukraine. The assessment process may well prompt a change in perspectives and plans for work at the site which had been conceived before the first careful visits. New understanding can then inspire new concepts for small or large preservation projects at the site, with greater probability of success.

Considerations in Preliminary Assessments

A wide variety of observations, measurements, and evaluations are listed below as possible components of preliminary assessments. Few cemetery preservation projects will incorporate all of these components in early assessments (and most mass grave sites can use a much narrower list). This broad list of considerations is intended to aid the planning of site appraisals and to expand awareness of site potential and latent concern during the assessment process. For many evaluation items, only tentative identification or measurement is possible in this initial phase.

- burial site location: GPS, address, village or municipality, raion, oblast

- site terrain: perimeter shape and length, area, slope, altitude, compass orientation

- formal/legal land ownership vs. informal/claimed ownership

- stakeholders: local civil authority, neighbors, nearest active Jewish community, descendants of former Jewish community and non-Jewish diaspora

- activists working at site: past and present

- annual climate: temperature, precipitation (rain and snow), solar irradiance, wind

- fences, walls, gates, locks: presence, location, type, materials, condition

- directional and informational signage: presence, location, materials, condition, languages

- grave markers: presence and number, location, condition (standing or toppled, intact or broken), materials, styles, orientation, epitaph languages

- ohels: presence, type, condition, access, signage

- community memorial monuments: presence, location, type, materials, condition, orientation, languages

- other man-made objects: power wires/poles, transformers, telephone wires/poles, gas piping/regulators, water piping/pumps, sewer access

- vegetation: planted and/or wild, location, type (including benign or poisonous), size, age, condition

- animals: presence, location, type (including benign or dangerous), nests/hives/burrows

- fungi: presence, location, type (including benign or dangerous)

- non-traditional burial site use and misuse: recreation, grazing, gardening/crops, paving, overbuilding, digging, looting

Examples of Simple Assessments

Two recent examples may serve to illustrate several components of simple assessments made as part of the broad survey of Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine conducted for this website. Both examples are at sites with few or no clear signs of their original and enduring Jewish community purpose, as is the most common situation in the region, but in both cases other researchers have worked to reveal and document evidence, and neighboring residents retain and speak of the history of the site.

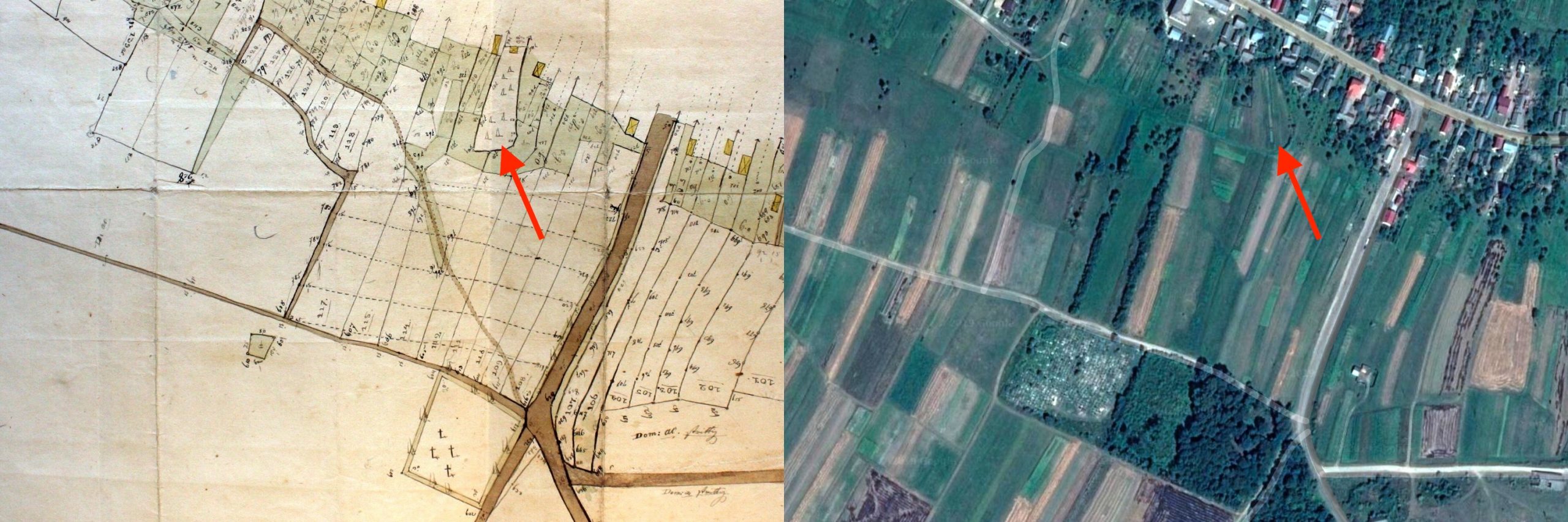

The first example is the old Jewish cemetery in Svirzh (Lviv oblast), one of two Jewish cemeteries recorded in the village on several databases including ESJF European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative, the IAJGS International Jewish Cemetery Project, and the now-idle Lo Tishkach European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative. At the time of the first site assessment for this project, one of the databases gave inadequate geographic information to determine the actual location, and surprisingly the other two databases misidentified an abandoned historic Roman Catholic cemetery as the old Jewish cemetery, probably due to mistaken information from local people. An 1845 (Austrian-era) property sketch for the village preserved at the Ukrainian State Historical Archive in Lviv shows both Jewish cemeteries at rough scale, but more than adequate to determine the location, shape, and approximate size of the old cemetery. Modern satellite views (Google, Bing, HereWeGo) of the location confirm that visual evidence of the cemetery perimeter persists today.

The old Jewish cemetery of Svirzh (red arrows) on an 1845 cadastral map and on a modern satellite image. Map courtesy of TsDIAL and Gesher Galicia; satellite imagery © CNES/Airbus, Maxar Technologies, and Google.

Examination of the cemetery both in satellite views and on a first evaluation confirmed that the burial ground is currently used for animal grazing and for light agricultural crops, as are all of the surrounding land parcels behind a row of houses which front on the road; no buildings appear to be present on the cemetery itself. Pacing the site and digital tools on satellite images estimate the perimeter of the cemetery at approximately 220m length, incorporating roughly 0.30 hectare of area. Interestingly, the old Jewish cemetery is much closer to the former village center than any of the much larger Christian cemeteries about 250m down a slope from the main road, but all of the cemeteries are at some distance from the historical castle at the edge of the village.

Like many Jewish cemeteries in the region, the old Jewish cemetery of Svirzh lacks even a single matzevah or any other marker, fence, sign, etc.; erasure of burial sites such as this was generally complete during the Nazi and Soviet periods in western Ukraine. However, memory of the site and the former Jewish community remains in Svirzh, especially near the old cemetery: interviews with neighbors confirmed the cemetery location, and older residents also knew the locations of a prewar synagogue and a school not far away; residents born in Svirzh before the war were eager to tell what they knew. During this first assessment, no evidence of any active heritage project at the cemetery was visible. These observations were recorded in notes, photographs, and screenshots. (Note: this cemetery is also the subject of a preservation project case study on this website.)

A panorama of the old Jewish cemetery in Svirzh as viewed from the south, from a visit in 2017. Photo © RJH.

The second example is the Jewish cemetery of Hvizdets (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast), a large village better known for its 17th-century timber-frame synagogue (now destroyed, but its painted ceiling and roof were recreated for the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw). The cemetery was well documented in 2019 through historical records and maps research and an aerial survey by ESJF, giving via text and images the location, shape, and size of the cemetery, roughly 380m in perimeter length and incorporating approximately 0.65 hectare. ESJF’s survey team also noted that the cemetery, although cleared of headstones and other visible indications of its original purpose, was not built over, but needed clearing (of wild vegetation) and fencing. ESJF also reported seeing two stone fragments resembling gravestone remnants, and that locals had said there is an unmarked mass grave at the site at an unknown location.

A subsequent walkover survey for this website confirmed the information ESJF recorded, and added a few additional details from observations and an interview with a cemetery neighbor whose family has lived adjacent to the site since before the German occupation. The cemetery terrain is significantly sloped at the center, and is bordered on two sides by a creek which has likely run there for centuries. Most of the wild vegetation consisted of tough grasses (dried and matted at the time of the visit), but several large shrubs and medium-sized trees, some perhaps originally planted for fruit, also dotted the landscape. A very large electrical power transformer is installed on the cemetery adjacent to a road, and connected to related structures (wires, poles, anchors, and stays) also on the cemetery land. Portions of the landscape also appeared to have been recently used as a dumping ground for rocky soil removed from a building project. Walking paths crossed the site, and wooden planks were set to bridge the creek at the paths.

From the cemetery neighbor, we learned that he grew up next to the site, the history of which he had learned from his parents, and he had played among some number of remaining Jewish headstones as a child before those were also taken for unknown building projects. Despite the overgrown grasses and a layer of soil, the neighbor was able to locate and uncover a medium-sized headstone fragment with a visible Hebrew inscription; he said there were a few others elsewhere on the ground, difficult to find now under the grass. He also advised that one stone which appeared to be the stump of a matzevah was actually the remains of an old footbridge foundation, and had no inscription. After discussing the cemetery, he pointed to the location near the center of the cemetery where he was told Jews were buried in a mass grave after a killing event during the war. These observations were recorded in notes and photographs during the visit.