![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Introduction

Almost every Jewish cemetery project of any type begins with a preliminary assessment of the site and its features, and that assessment typically includes at least a walkover survey to see first-hand the setting and condition of the site. For some cemeteries and mass grave sites, that walkover may be the only survey needed to develop project concepts, plan, and begin work. However, many projects benefit from more precise and detailed surveys of the history, legal status, location, perimeter, and environment, as well as inventories of markers, vegetation, and other objects in the space; these and other surveys are described here with a selection of regional and foreign examples for consideration.

For some projects, especially those focused primarily on documentation and communication, one or more surveys may be the primary objective of the project itself. For other projects, surveys are typically best conducted early in the project plan, but depending on site conditions revealed in the preliminary assessment it may be best to postpone some types of surveys until an overall project concept is in development or has been completed, overgrowth is cut back and removed, and project funding is identified. Some survey types are relatively simple and inexpensive, and others have inexpensive options which can be performed by lay persons, but for some project types the necessary surveys may require trained professionals, or expensive instruments, or both.

A photogrammetric study of matzevot in the new Jewish cemetery of Rohatyn. Photo © RJH.

The potential for high cost highlights the importance of identifying the intended use of survey results before engaging in any survey. This is especially true for projects which require some form of measurement data or specific inventory as an input to plans, designs, or other documentation: identifying the necessary data formats, accuracy, and precision ahead of the measurements will determine the specific types of equipment and expertise which are suitable for the purpose. In the sections below and on a related survey tool page on this website, alternatives are given for several of the survey types to allow trade-offs to be made between cost, complexity, and data quality.

The associated references section on surveys on this website provides links to printed and online resources which describe survey methodologies and provide application examples from regional and foreign sources. In the case studies section, you can find examples of cemetery preservation projects which incorporate various surveys to create and preserve information about Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine.

Site Survey Categories

This is a long page, divided into different site survey categories, most with several survey types describing the variety of potentially useful data-gathering approaches. To help in navigating this page, the categories are listed here in the same order as they appear below:

- Historical Civil and Jewish Community Context

- Modern Civil/Legal Status

- Landscape Boundaries and 3D Surface Profile

- Fixed Objects and Features Inventory

- Subsurface Objects and Features Inventory

- Flora and Fauna

- Environment

Historical Civil and Jewish Community Context

Desk-based and archive research can be valuable to discover, define, and document the history of Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine, even without stepping foot on the sites themselves. Information about the number and locations of prewar Jewish cemeteries and wartime mass graves is available for many regional settlements on websites as well as in several historical archives in the region and beyond. Digital and physical archives are especially useful for maps and their related property registers and valuation data. Historical descriptions of the evolution of Jewish community management of prewar sites, and of the Holocaust histories which resulted in mass burials, can be found in Yizkor books and other memoirs of Jewish families and lost communities. The references section on surveys lists and links to many of these resource types, but key aids are briefly described here:

Ukrainian national and regional historical archives: The records of both civil authorities and self-managing prewar Jewish communities are preserved in western Ukrainian archives for some places, although many records were lost or destroyed in World War II. Useful text records for preservation projects may include property purchase and ownership registers, letters between Jewish community leaders and local civic administrations about the historical management of cemetery properties, property divisions and mergers, public health concerns, civil disputes, and legal actions. All Ukrainian state historical archives in the region retain such records which may be requested and inspected upon presentation of suitable credentials; the archives include the national archive in Lviv (TsDIAL) as well as the regional (oblast) archives of Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil, Chernivtsi, and Zakarpattia. No records are available for searching and viewing online; research must be conducted in person, either by project activists or hired professional researchers.

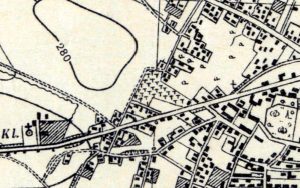

The archives of Ukraine are quite valuable as a source of detailed historical property (cadastral) maps, both for the Austrian period (to 1918) and for the interwar period (to 1939); these maps can help to establish precise prewar property boundaries for Jewish cemeteries, allowing for unrecorded expansion of cemeteries after the latest map date until the war. Such maps are available for many communities at TsDIAL and the regional archives listed above (except Ivano-Frankivsk).

Christian and Jewish cemeteries in Dobromil ca. 1852. Original map © Polish state archive in Przemyśl. Composite digital image © Gesher Galicia.

Other physical archives: In general, all archival materials related to civil and religious communities on lands now in western Ukraine are meant to be preserved in Ukrainian archives. However, there are isolated examples of community and property records (including cadastral maps) at archives in other countries. For example, an 1852 (Austrian-era) cadastral map of Dobromil (Lviv oblast), which accurately depicts the Jewish cemetery boundaries as of that survey year, is preserved at the Polish state archive in Przemyśl; searches of cadastral maps at that archive can be conducted online (search fond/zespołu 126 for freely accessible map images, or by geographic index for other records), and professional researchers can acquire higher-resolution scans of the maps for detailed planning work. Relevant materials may also be found in Polish state archives in former western Galicia such as Kraków, Rzeszów, and others.

It is possible that materials relevant to surveys, boundaries, etc. of Jewish cemeteries and mass graves in western Ukraine may also be found in archives and libraries elsewhere in Europe, and in Israel, North America, etc., including for example the large digital and physical resources at Israel’s Yad Vashem, as well as the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People (CAHJP), and the National Library of Israel – some with online access.

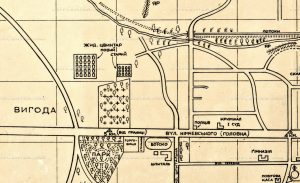

This 1939 street map of Sniatyn clearly shows the two Jewish cemeteries in the town. Image courtesy CUHECE.

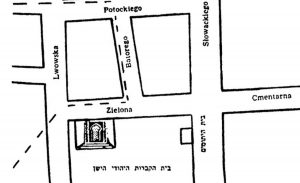

Digital map and register collections: Digitized historical maps useful to at least locate and in some cases detail Jewish cemeteries in western Ukraine can also be found in a variety of free-access web collections. For example, an important collection of historical maps is freely available online in the Urban Maps Digital project of Lviv’s Center for Urban History of East Central Europe. The project has broad geographic scope but concentrates as a priority on Lviv and other cities and towns of Ukraine. Among the valuable items is a Ukrainian-language 1939 street map of Sniatyn (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast), which schematically depicts the location and size of the town’s old and new Jewish cemeteries; the burial sites have otherwise been difficult to locate in recent years, and the old cemetery is now erased, without standing headstones.

The old Jewish cemetery of Rava Ruska on an Austrian second military survey map. Original map source: Kriegsarchiv Austria. Composite digital image courtesy Mapire.

The Mapire project presents several historical maps in stitched format plus overlays on modern street or satellite maps. Among the available maps covering western Ukraine are the second military survey of the Galician portion of the Habsburg Empire (1861-1864) and the third military survey (1869-1887), both of which show some Jewish cemeteries as depicted in the hyperlinks here for Rava Ruska (Lviv oblast) and Tovste (Ternopil oblast). In military and other official survey maps, often the Jewish cemeteries are either not depicted, or are tagged with a cross (as Christian cemeteries are), which can make interpretation difficult.

Many geographically-indexed historical maps of greater Poland (including western Ukraine, which was part of Poland several centuries ago as well as during the interwar period) are available through the digital map archive of the Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny. High-scale regional maps are presented linked to the Mapster application, including a 1934 map of Zolochiv (Złoczów, Lviv oblast), which depicts a Jewish cemetery west of the town center using “T” symbols instead of crosses. Many other types of maps are also available on the site which may aid research for some cemetery projects, such as geological overlays and map series which can help to understand the evolution of Jewish cemeteries in larger towns.

A partial collection of Austrian-era high-scale and accurate cadastral maps in stitched format for individual towns and villages in eastern Galicia is available in the Gesher Galicia Map Room, including an accurate and highly detailed 1853 property map of Khyriv (Chyrów, Lviv oblast) which clearly details the now-overbuilt old Jewish cemetery; the new Jewish cemetery of Khyriv is not depicted because it was outside the cadastral area for the town (and was probably established after the survey for this map). The online resource also presents a large number of regional maps dating from the late 18th century to the mid-20th century; elsewhere on the Gesher Galicia website, the All Galicia Database presents a searchable database of indexed historical records for the region, including property records which include entries for the Jewish communities which owned the cemeteries before WWII.

A 1944 aerial photo of the old Jewish cemetery in Rohatyn. Source: NARA, acquired by Dr. Alex Feller.

Luftwaffe WWII Aerial Photos: A cache of more than a million aerial photographic images taken by the Luftwaffe across Europe and Africa between 1939 and 1945 was recovered by Allied forces at the end of WWII and is now preserved in duplicate in US and UK national archives. Images available for western Ukraine depict cities, towns, and villages with fairly high resolution and acceptable distortion, making them quite useful for identifying and documenting Jewish cemeteries from before and during the German occupation, as well as a number of wartime Jewish and other mass graves. A 2017 example for Rohatyn (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast) is presented in overlay format with user-selectable transparency on a modern satellite image, and includes historical background information and interpretation, plus hyperlinks to the current source archives. The same image has been used to detail features of both Jewish cemeteries in Rohatyn as heritage objects.

Similarly, a pair of reports from 2020 for Jewish Heritage Europe demonstrates how a series of seven Luftwaffe images spanning 1939 to 1944 permit analysis of the Bagnówka Jewish Cemetery and the Rabbinic and Bema Cemeteries (among other Jewish built heritage) in Białystok, Poland, to support restoration and preservation efforts there.

The Stryi Yizkor Book includes a postwar memory map depicting the old Jewish cemetery.

Image courtesy NYPL.

Yizkor Books and related memoirs, genealogy societies, etc.: Further historical information and context for Jewish cemeteries and mass graves can be gleaned from a few of the published memoirs of pre-war Jewish émigrés and wartime survivors of Jewish ghettos in western Ukraine, as well as Ukrainian witnesses to wartime events either still residing in the towns or who emigrated themselves after the war. In addition to brief historical summary chapters in the Encyclopedia of the Jewish Communities of Poland (Pinkas hakehillot Polin), extended multi-author memoirs of Jewish life before, during, and after WWII were produced for many towns in western Ukraine (and across Europe and beyond) as Yizkor (Memory) books. Both the Pinkas and the Yizkor Books are available in English for many communities on resource pages presented by JewishGen, the large Jewish genealogy organization; scanned images of many original Hebrew- and Yiddish-language Yizkor books are also available on the websites of the New York Public Library and the Internet Archive. An overview of Yizkor Books and an example for one town in western Ukraine is available on the website of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage. A rare but helpful example of cemetery identification and location is the 1962 Yizkor Book of Stryi (Lviv oblast), in which a memory map of the town drawn by a survivor after WWII shows the old Jewish cemetery situated between named streets from the Polish era; the cemetery is now overbuilt with apartment buildings and unrecognizable as a burial site.

Individual personal memoirs and witness accounts may also contain information relevant to cemetery and mass grave identification and documentation. Very few Jews were eyewitnesses to large-scale wartime killing events in what is now western Ukraine, but some survivors visited the sites after the German retreat, and small numbers of local Ukrainians were witnesses to some events. Some video testimonies of elderly Jewish and Ukrainian witnesses recorded by the USC Shoah Foundation and Yahad – In Unum can be used to identify Jewish cemeteries and mass graves in the region. However, both formal and informal memory books as well as personal testimonies often contain information which conflicts with other sources and with established historical records; as for any non-academic resource, the data gathered from these personal histories should be verified before being relied upon for projects at burial sites.

Modern Civil/Legal Status

Preliminary assessment of a burial site and the historical research described above will both inform a survey of the current legal, religious, and civil status of the site, which is important to nearly all project plans, even for informal projects. Each of the topics below bears on a different aspect of burial site status and the laws, traditions, or social norms which may apply to sites and projects.

Civil law and heritage registration: Several laws of the state of Ukraine are applicable to the inventory, preservation, and protection of cultural heritage and historic sites within its borders, including historical and architectural monuments, cemeteries, and other places of burial. In addition, Ukraine is a signatory party to certain international conventions which apply to the recognition and protection of cultural and national heritage. These laws and agreements are described in a white paper prepared for Rohatyn Jewish Heritage by Law Craft LLC and linked to the survey references page on this website. Evaluation of this information and its application to a specific Jewish burial site in western Ukraine should be made by an attorney licensed in Ukraine, but an informal summary of the key issues and data as they apply to regional Jewish burial sites and monuments is given here.

The Verkhovna Rada (Supreme Council) of Ukraine enacts and amends regulations governing historic sites, and created the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance (UINR) under the direction of the national cabinet of ministers through the Minister of Culture as the central executive body which implements state policy for restoration and preservation of national memory of the Ukrainian people. The responsibilities of the UINR have evolved significantly since 2014, and continue to do so. Much of UINR policy and data focuses on the development of the Ukrainian state, but aspects relevant to Jewish history and sites in Ukraine include accounting and preservation of the places of burial of victims of the wars, construction of monuments and memorial signs, research and preservation places of graves of war participants and political repressions, and research on historical heritage aimed toward integration of national minorities into Ukrainian society. Recent increased emphasis in Ukraine on the perpetuation of memory about the victory over Nazism in WWII includes recognition, memorials, and monuments to the (military) participants and to victims; the legal text specifically includes wartime fraternal (mass) grave sites.

An excerpt from the state register of heritage objects for Ternopil oblast, showing the Jewish cemetery and mass grave of Lanivtsi.

The Ukrainian national law on the protection of cultural heritage defines cultural heritage objects (which may include burial sites) and monuments as those heritage features which are entered in the State Register of Immovable Monuments of Ukraine. Entry of heritage objects in the State Register is by decision of the state cabinet of ministers (for objects of national value) or by the Ministry of Culture (for objects of local importance). At present the combined State Register includes more than 130,000 fixed historical and cultural objects, but few of these are Jewish burials sites and monuments. Any central government body, local council, Ukrainian citizen, or recognized organization may initiate an application for inclusion of an object in the State Register. Documentation requirements to support the application are defined and must include a brief historical survey, a summary of the object’s technical and physical condition, and photographs of the object in its current state. Recent meetings with Ukrainian legal advisors working in this field, and their experience to date, suggests that registration at the national level should be preceded by registration at local and oblast levels, and that registration of wartime mass graves requires archaeological excavation (which conflicts with Jewish religious law; see below). The existing registration of historical and cultural objects in a given raion may be learned by contacting district and oblast administrations directly, including those in Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil, Zakarpattia, and Chernivtsi. Note as an example that while the online State Register lists only two heritage objects in the Rohatyn raion (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast), and none in the town of Rohatyn, the list maintained by the oblast administration lists more than 60 objects in the raion, including four mass graves (Austro-Hungarian, Jewish, Soviet Army, and UPA).

An aerial view of the new Jewish cemetery of Zbarazh, which sees regular vegetation clearing by city workers. Photo © ESJF.

Another article of the law on the protection of cultural heritage assigns responsibility for the protection and maintenance of cemeteries, mass graves, individual graves, and all places of burial to the executive body of the village or settlement, or the city council, at the expense of the local budget, whether or not the burial sites are in the State Register. It is prohibited to demolish, change, replace, or relocate any memorial monuments installed at heritage sites, and the owner of these monuments (usually the local civic administration) is obliged to keep the monument in proper condition. Criminal charges and penalties may be brought against anyone found damaging a registered heritage object. A separate national law on burials and funerals assigns criminal charges and penalties (both fines and jail time) for the desecration of graves and the disturbance of human remains at sites of burial of any type.

Although Jewish heritage sites do not appear among Ukraine’s UNESCO-listed World Heritage Sites or sites in application for listed status, and likely never will be, Ukraine ratified the UNESCO Convention concerning the Protection of the World’s Cultural and Natural Heritage while under Soviet Rule and since independence still refers to the agreement (for example, in the text of the national law on the protection of cultural heritage). The Convention obliges Ukraine to ensure the identification, protection, conservation, presentation and transmission to future generations of cultural and natural heritage, according to conditions relevant in the country. Ordinary burial sites would not normally be included as having “outstanding universal value from the historical, aesthetic, ethnological or anthropological point of view” as defined in the Convention, but some recognition may be possible for a few well-preserved Jewish cemeteries in western Ukraine.

Jewish religious law and tradition: Jewish religious law, or Halakha, governs the behavior of observant Jews in their religious practices and in their ordinary relations with each other and with non-Jews. An elastic collection of biblical commandments plus rabbinical case law, augmented by centuries-old customs and traditions, decisions made under Halakha normally require rabbinic interpretation, although many lay Jews make their own working decisions about how laws and customs apply to new situations.

Only a small portion of the body of Halakha and traditions addresses issues at Jewish burial sites. One very important perspective is that any burial site or grave, of even one Jew, is considered a cemetery and requires the same consideration as a regular community cemetery; wartime mass graves are also cemeteries in this Jewish tradition. Another essential religious rule is the prohibition against disturbing a grave, including the earth above the body; in general, soil and other materials may be placed over the grave, but neither a body nor the soil above may be removed except under extreme circumstances. An explanation of the religious law regarding exhumation and some rare circumstances when it may be permitted was given by Michael Schudrich, Chief Rabbi of Poland, at the IHRA-sponsored conference in 2014 on (Jewish) Killing sites – Research and Remembrance, and will not be discussed further here. As practical guidance for Jewish burial site projects in western Ukraine, the key messages are to treat every burial site with respect for the dead, and to avoid any form of digging within the burial site boundaries without rabbinic supervision.

Beyond these hard principles, there are many other Jewish rules and traditions which address the practices and behaviors appropriate for visiting and caring for cemeteries and mass graves. Most of these rules are created by Jews for Jews, i.e. they do not (necessarily) apply to non-Jewish (Gentile) visitors, caretakers, etc.; hand-washing, and head covering for men, for example, are not applied across faiths (though any Gentile may choose to follow the Jewish traditions out of respect). There is no single comprehensive list of cemetery-related Halakha and tradition. One knowledge base details the laws and customs of Jewish mourning in two printed volumes; the chapter on laws applicable to visiting a cemetery runs to many pages with nearly 500 footnotes to religious source texts. This resource is written explicitly to guide Jews wishing to visit the graves of their ancestors or tsadikim, but covers a great number of related concerns, including for Jews visiting the graves of Gentiles. However, very few practical questions which arise in the planning and development of cemetery preservation projects are addressed; for these questions, the advice of a regional rabbi, as well as common sense and courtesy, are the only reliable authorities. It is wise to remember, for example, that in western Ukraine nearly all historical cemeteries (regardless of community type) are owned by the administration of the local village or town, which gives that organization both authority and responsibility for its security and care; a cemetery may be “Jewish” but it is legally Ukrainian, and project work at a burial site normally requires permission from the local village or town council.

Other religious and civil society norms: Jews and local authorities are not the only stakeholders with a spiritual and/or tangible interest in Jewish burial sites in the region. For example, western Ukraine has a very strong Christian religious tradition, and church leaders watch over their entire parish area, including the people and heritage outside of their own faith. Respect for burial sites and honoring the dead are widespread in the region, and there have been numerous instances of priests and other religious leaders initiating or joining Jewish memorial ceremonies, calling for the recovery of displaced Jewish headstones, and re-burying Jewish mortal remains in Jewish cemeteries, with education and tolerance teaching as motives for engagement. Because of their influence and guidance in nearly all communities of western Ukraine, it should benefit most Jewish burial site preservation projects to open an ongoing two-way discussion with local leaders of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Churches, Roman Catholic Churches, Eastern Orthodox Churches, and others which may have followers in an given locale.

Respect for beliefs should also include observance of the relevant sabbaths and religious holidays. As Saturdays and Jewish religious holidays are normally days of rest and prayer with no physical work permitted, in western Ukraine the larger Churches observe Sundays as their sabbath, and follow the Julian calendar (Old Style dating) for observance of their Great Feasts, which normally also prohibit physical work. In May and a few other months of the year, scheduling extensive project work requires strategy and planning.

Ukrainian students and other volunteers clearing brush from the Jewish cemetery of Kalush. Photo © RJH.

In addition to religious teachings, civil society norms increasingly influence the relationship of local citizens to the heritage of their towns and villages in western Ukraine. Volunteers in many places organize clean-up and repair days of cemeteries and other shared heritage sites, often with local council leadership and participation. Joining cross-cultural volunteer efforts in these places makes possible the inclusion of Jewish burial sites in future events, and promotes a sense of responsibility in local people for all of the heritage sites where they reside; the clearing and cleaning of an overgrown Jewish cemetery in Kalush (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast), for example, was successful through the skillful blending by the project leader of resources from the local schools, city workers and other community members, plus Ukrainian and international civil society volunteers. At the national level, Ukraine’s efforts to more deeply engage with the European Union and western societies in general prompts government participation in international professional and policy-development organizations, such as the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), can prompt national and local support for and participation in heritage projects.

Other stakeholders: Many, perhaps most, of the Jewish burial site projects conducted in western Ukraine are started either by local Ukrainian heritage activists or by Jewish descendants of families who lived in the area before and/or during WWII. Project leaders who fit one of these two categories benefit from seeking out people who fit the other category, for partnership and task sharing. Usually the success of preservation projects depends on a variety of skills, knowledge, and other assets which are not broadly distributed in either group, but blend well through cooperation. See the guide page on communication and its related references page on this website for more information about searching for and connecting with cross-cultural partners.

Landscape Boundaries and 3D Surface Profile

New technologies to address long-running issues: UAV survey tools in Ukraine. Photo © ESJF.

There are many tools and methods to survey through measurements and analysis the boundaries and terrain (surface profile) of Jewish cemeteries and mass graves. A good introduction to land surveying techniques is available in English on Wikipedia, and there are other good references available in both English and Ukrainian as well. As described in a page on this website which details many of the tool types used in survey work, the range of capability and cost of this equipment is very broad, from simple and inexpensive measuring devices costing around US$10 to sophisticated optoelectronic devices costing many thousands of dollars. Similarly, some of the measurement methods are intuitive or can be learned by novices in a few minutes, while others are best left to hired experts who have the appropriate training and experience. This is a reminder of the caution given in the introduction to this page, that identifying the intended use of survey results, and the necessary accuracy and data format for that purpose, should determine the specific survey tools and methods to be used for any preservation project. It is also important to consider what is already known about the cemetery landscape from preliminary assessment and from maps, records, and other documentation that can be explored as part of desk-based research. Some features of burial sites (e.g. right-angle boundary corners or sharply-defined permanent landmarks) can simplify the survey process. It can be effective and efficient to also consider possible project extensions or related work during the planning stage for a landscape survey, and in particular to consider how the data formats may be used in communication about the project with local authorities and the general public. In general, all of the survey methods described here are feasible in western Ukraine, and availability of equipment and experts should not limit the selection for a particular project.

The Balamutivka Jewish cemetery documented through historical research, boundary mapping, and low-altitude UAV survey. All images © ESJF.

Simple identification of burial site location, plus boundary definition: Ongoing research by organizations such as ESJF European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative, Yahad – In Unum, and others has already located nearly every prewar Jewish cemetery in western Ukraine and a large portion of the known or reported wartime mass graves, as tabulated in the identified cemeteries section of this website. For many preservation projects, the available online data posted by these organizations may already be sufficient for project planning and cost estimation; see for example the compiled research, mapping, and survey data for the Jewish cemetery of Balamutivka (Chernivtsi oblast) in the ESJF online database. Each of these organizations can make their larger data sets and more detailed documentation available to serious prospective project activists to support site protection and preservation.

However, some projects may require more or different data for design work, or to coordinate project aspects managed by various activists. In the guide section for preliminary assessments, we described the “walkover survey” as a useful baseline evaluation of cemetery boundaries and terrain. Starting with this most basic survey, various methods are described here in generally increasing complexity and cost, with remarks about how the resulting data may be used in project planning and design. The specific tools and instruments are mentioned only briefly here; refer to the tools page for more details.

Estimating the dimensions of the Jewish cemetery of Katerynivka using Google Maps. Source data shown in the image.

Internet mapping websites as described on the guide page for preliminary assessments or the historical maps and aerial photos described above on this page can in many cases provide initial estimates of cemetery boundary shape and length, if such information is not already available from ESJF. The “measure distance” tool on the satellite view of Google Maps, for example, can easily calculate a boundary length and an enclosed area on many devices, if the cemetery is visually distinct from the surrounding landscape in aerial views; the estimates for the Jewish cemetery of Katerynivka (Ternopil oblast)shown here demonstrate the simplicity of this approach. Paper and digitized paper maps which depict Jewish cemeteries can similarly be scaled and measured using simple graphical tools on computers. Note that most digitized maps and aerial/satellite views are limited in precision by their resolution and in accuracy by distortions in scanning, camera lenses, and seamless stitching for online presentation.

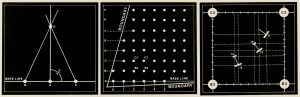

On the ground at the site, pacing (calibrated by practice with a tape measure) may provide sufficient boundary accuracy for initial or even final design and costing of fences and gates, especially if the terrain is mostly free of obstructing vegetation and steep slopes. Directly measuring the entire boundary with a tape measure significantly improves accuracy; tape measures of 30m length or more are available in western Ukraine for US$10 to US$20, to measure larger cemeteries. Combining two or more tape measures allows a quick measurement of corner angles for cemeteries with irregular shape, using the law of cosines from simple geometry, which can provide greater accuracy than sighting along a protractor. A precision survey compass with an integral optical sight can also be used for this purpose; precision compasses are often sold as sporting equipment (for orienteering) or as military surplus/copy, for US$10 to US$40.

These methods all benefit from the use of ordinary survey stakes pressed into the ground to temporarily identify start and end points in a measurement chain, as well as geometric construction lines for calculating angles.

A Soviet topographic map showing the Rohatyn old Jewish cemetery. Image courtesy Routes to Roots Foundation.

Simple measures of boundary and terrain slope: Coarse indications of absolute or relative elevation around and within some cemeteries for planning purposes are available on topographic maps and in some free web applications. Although little available topographic data is mapped at high enough scale to give useful guidance for cemetery projects, Soviet surveys of western Ukraine from the 1980s mapped at 1:5000 scale are sufficiently detailed for basic planning, as in an example for Rohatyn (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast). Archives and government research may reveal additional sources for historical and recent high-scale topographic maps.

An internet search for free web applications providing altitude data gives several examples, including Google Earth (for Chrome), which displays approximate altitude (to the nearest meter) at the cursor location, and a simple tool which accesses global elevation data, merging it with a clickable OpenStreetMap view (for any browser). Experience with a number of Jewish cemeteries in western Ukraine demonstrates that the underlying data in these tools is typically interpolated across a coarse grid and is often not sufficiently fine to represent actual slopes in and around burial sites.

On the ground at the site, improved relative elevation measurements (including slope or grade) can be made at discrete locations using an inclinometer (also called a gradiometer or slope gauge). Simple forms can be made from a protractor and a plumb bob or line level, all simple and low-cost tools widely available at large hardware and construction equipment shops in western Ukraine. Measurements of slope, when combined with distance measurements between survey points, provide a measure of relative elevation in chain format useful for plotting the site topography.

Precise measurements of boundary and slope: Specialized instrumentation can provide much more precise distance, angle, position, and elevation data than the simple methods, for those Jewish burial site preservation projects and plans which require refined data. Traditional survey instruments such as the optical level accurately measure distance in a horizontal plane and relative height with respect to that plane, plus rough measurement of angles between identified points or objects; practical single distance measurements can be made to 0.05% (about 1cm error in 20m span). The more sophisticated optoelectronic total station theodolite can simultaneously measure long distances at even higher accuracy plus precise horizontal and vertical angles between points, using laser and computer technology to eliminate human errors and point placement variation. Few cemetery projects require the millimeter accuracy of a total station measurement, but the instrument can significantly speed measurement times so that a detailed survey with many more points can be made in a day’s time. The cost of the equipment and training is high, but instruments can be rented in western Ukraine, and survey services can be hired. In late 2019, a 50-point, 1-hectare Jewish cemetery survey in the Ivano-Frankivsk oblast was quoted at US$350 plus travel costs; data output was to be in the form of a spreadsheet plus DXF interchangeable CAD file.

A GNSS receiver in use as a control point for a GPR survey at the south mass grave in Rohatyn. Photo © RJH.

Specialized survey measurements: Cemetery preservation projects rarely require the measurement of true geographic point position, as it is usually more useful to know where boundaries and objects are located relative to other nearby physical features, independent of their position on the globe. However, for some mapping applications to communicate project plans and status, or to establish reference points for land survey work, sometimes it is helpful or necessary to identify the location of points within a geographic coordinate system.

While most modern smartphones include or allow for simple GNSS (GPS) applications, the basic resolution and accuracy of those tools is currently low, e.g. within a range of a few to several meters. Advances in the European Union’s Galileo satellite navigation system, which overlaps western Ukraine, may soon improve that accuracy to one meter, which should be sufficient for many types of cemetery projects. For better accuracy, dedicated GNSS receivers which incorporate a satellite-based augmentation system (SBAS) such as the European Geostationary Navigation Overlay Service (EGNOS) can significantly improve location accuracy, to about 60cm in real-time and 2cm with post-processing, although that capability is not yet available with Galileo.

To further evaluate and measure burial site 3D surface profiles, and in some cases to analyze the landscape to detect and define the location of hidden mass graves, image-based and range-based techniques such as low-altitude aerial photogrammetry and lidar may be used, as in a non-invasive forensic research example in Cyprus. The methods are data- and computationally-intense, producing output which is both quantitative and graphical, each format serving specific purposes. Most of the cemetery surveys conducted by ESJF in western Ukraine are driven by large photograph datasets taken by cameras on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, or drones) and then post-processed into composite images, point clouds, boundary models, and rough digital elevation models. Scanning with lidar equipment has the advantage of filtering out vegetation from the point cloud, allowing remote surveys of tree-covered burial sites. The purchase cost of the equipment and software is high, but can be spread over multiple projects (as in ESJF’s work) or contracted as a service. A quotation in 2020 for a 1-hour aerial (drone) survey of a 1-hectare Jewish cemetery in the Ivano-Frankivsk oblast was US$450 plus travel, with output as a DXF file, point cloud, and video and photo set.

Fixed Objects and Features Inventory

Some of the techniques employed in defining burial site boundaries and landscape surface profiles are also useful for locating and mapping fixed objects within the boundaries, from traditional matzevot (grave stones) and postwar memorial monuments, to important trees and other key vegetation areas, to unrelated man-made objects such as utility poles, electric power transformers, and postwar buildings. In addition to measuring and recording the locations of these objects, for the special case of grave stones some additional assessment, interpretation, and documentation guides are referenced below, to aid in assembling a current “inventory” of the cemetery contents.

Using tape measures to record the location of a headstone stump in the

old Jewish cemetery of Rohatyn. Photos © RJH.

Recording the location of fixed objects: The position of objects within cemeteries, whether relative to known fixed reference points or in absolute geographical space, can be measured and recorded using the same tools and methods described above. The simplest approach for many projects is just to use tape measures referenced to cemetery fences (especially corners, where they are defined) or other permanent cemetery or boundary features. While true geographic position data is helpful for simply creating digital object maps, it is not actually necessary and may not be helpful for the planning and design stages of a landscaping or monument project, which typically rely instead on 2D or 3D layouts.

If there are more than a few objects to record in a cemetery, it can be helpful to set up a simple measurement grid within which to document the objects. A very helpful introductory article in the Journal of the Association for Gravestone Studies (“Recording cemetery data”; Markers, Vol. 1, 1980; page 99 – see the survey references page on this website) describes and illustrates many methods for documenting cemeteries, including creating a cemetery diagram or map, with advice about using geometric principles to construct perpendicular grid lines (even in cemeteries with irregular boundaries) and to rapidly measure or estimate object locations. Other methods described above, including with specialized instrumentation, may also be used, but for many small- and medium-sized burial sites the simple layout approach plus tape measures can be more than adequate.

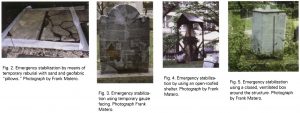

Grave marker stabilization methods in a reference article by Frank Matero and Judy Peters. Image © UPenn.

Inventory and assessment of headstone condition: The survey references page also includes a number of important books, articles, web pages, and videos which may aid the inspection and documentation of many types of grave marker materials and their condition – and may indicate that emergency stabilization of some grave markers is warranted before other phases of a project begin. These topics are especially well covered by references from the Association for Gravestone Studies (as above), the US National Center for Preservation Technology and Training, the University of Pennsylvania, the Getty Conservation Institute, and Lviv Polytechnic National University; see also the resources on the stone conservation references page on this website. Note that the photogrammetry and laser scanning techniques described above for entire cemeteries can also be used on the much smaller scale of individual headstones, for documenting the inscriptions and carvings as well as recording a snapshot of the current state of decay; in the absence of active physical preservation plans for the stones, these 3D images and models can be important records of the heritage.

Documentation of headstone design and carvings: Photographing, recording and interpretation of matzevah inscriptions and symbolic carvings specific to Jewish headstones typical of the region of western Ukraine are also described in many other resources on the survey references page. The topic is sufficiently large and specialized that we don’t attempt to summarize it here, but instead highlight key articles and examples by Philip Trauring, Michael Nosonovsky, Ivan Yurchenko, and Khrystyna Boyko among the articles, reports and web sites on the page. See also case study 04 on this website for book-length examples of cemetery documentation in western Ukraine and beyond, and case study 02 for digital database versions.

Subsurface Objects and Features Inventory

Jewish cemeteries in western Ukraine suffered significant damage by occupying regimes during and after World War II; very few cemeteries in the region are intact, and most are devastated with scarce signs of their original purpose, design, and use. During the decades since the war, many Jewish burial sites have been in repose and decay, accumulating wild vegetation and the natural decomposition which accompanies it. In some cemeteries, there may be fallen headstones or the lower portion of broken headstones just under the visible surface of the site. Especially at mass killing and burial sites, the actual location of the physical grave or graves may not be known. As noted above in the section on legal issues, Jewish religious law (Halakha) prohibits disturbing the earth above Jewish graves, in particular excavation, but there are methods available to assess the location of mass graves and what other objects may lie just under the surface.

A mechanical probe used to locate a hidden headstone stump in the old Jewish cemetery of Rohatyn. Photo © RJH.

Mechanical probes: As shown in the page on tool types used in survey work on this website, a common tool used in the management and maintenance of cemeteries in the US and Europe can be adapted to search for buried headstones and headstone stumps in Jewish cemeteries: the T-handled probe. Regardless of what type is used, the depth of soil penetration should be mechanically limited to avoid disturbing buried human remains; normally this means setting stops on the probe tip to 25cm or less. Probing for buried stones can be conducted at suspected locations from other observations or in a gridded survey system. If an unknown stone is struck while probing, limited excavation to a shallow depth to expose part of the stone should be sufficient to determine whether the object is actually part of a headstone or is an ordinary rock or another hard object (bottle, brick, etc.). In case of concerns about the probing process or exposing buried matzevot, rabbinical guidance on the specific issues is recommended.

Geophysical instrumentation: In her text “Holocaust Archaeologies” (see the survey references page on this website), Dr. Caroline Sturdy Colls details several methods for performing non-invasive scientific surveys of mass graves and other sites of Holocaust violence, without disturbing human remains or the earth above them. In addition to walkover surveys, maps and other historical research, plus lidar and photogrammetry studies, Dr. Sturdy Colls describes geophysical surveys using methods of ground-penetrating radar (GPR), resistance probes, and magnetometry, among others, based on her experience researching numerous sites of violence and wartime camps at locations in Poland, Serbia, and the British Channel Islands. All of these methods are in use in Ukraine by both Ukrainian and foreign archaeologists. The selection of method(s) depends on the strategy to address local conditions; for example, clay layers in soils at some locations in western Ukraine can cause excessive reflection in GPR measurements, making data analysis very difficult, and other methods (e.g. metal detection and gravitational survey or sonar) will only succeed with specific types of subsurface objects or formations. In her text, Dr. Sturdy Colls provides guidance on the selection of survey equipment and methods, and on managing expectations about the data and interpretation.

Flora and Fauna

The guide page on landscape planning, development, and care on this website discusses the relationship between existing and planned vegetation in cemetery projects, and the management of landscape ecosystems including insects, birds, and other animals. More information about surveying wild and planted trees, shrubs, grasses etc. is included on that guide page and on the corresponding landscape references page. These resources cover not only benign plants and animals but also perceived pests and poisonous organisms commonly found in open spaces in western Ukraine. Survey methods for plant and animal species at Jewish burial sites are simple, typically conducted through walkover surveys, photography, and limited sampling for further research, so no additional guidance is presented here, only the reminder to include a survey of the life in the cemetery along with other observations, measures, and documentation.

Environment

Finally, it is important to observe and document what lies outside of cemeteries and mass graves in addition to recording what is inside, as the environment (and for urban sites, the neighborhood) and the burial site can each affect the other in many ways, impacting preservation projects planning, progress, and success. Assessing and documenting the environment can usually be accomplished through walkover surveys of the neighboring landscape, but studying maps and online data as well as municipal records (property ownership, past legal action, etc.) may also be warranted. Some of the environmental factors can be evaluated on a single site visit, while others are best studied at several times of day (and night) and at least sampled in all seasons. Among the factors to consider are:

Solar irradiation: Awareness of the daily and seasonal sunlight which illuminates burial places can help with project planning, including not only landscaping but also the placement and orientation of monuments and signage. The rising popularity and affordability of solar energy conversion systems around the world has made a number of tools available for simple research using simple internet searches for solar resource and photovoltaic power potential data. For example, the Global Solar Atlas, a project of the World Bank, features a searchable map showing basic solar data across the Earth. Searching the tool for sites in Ukraine is best done using the Ukrainian spelling for place names, or with GPS coordinates. Irradiation data at the Jewish cemetery of Kremenets (Ternopil oblast) is shown here in several formats geared toward solar panel installation, but still useful for preservation project planning. As the Krements example well demonstrates, it is important to factor in the actual terrain slope at the site in any calculations and plans using solar data.

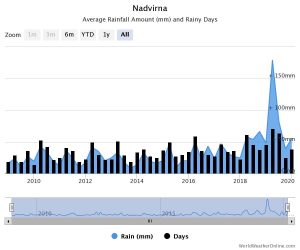

Climate and rainfall: Current and historical climate measures of many places in western Ukraine is also relatively easy to search online, in order to inform project plans at burial sites. The largest towns in the region are easiest to find on many free websites; where data for smaller towns and villages is not available, good estimates can be made by interpolating data from nearby places with more complete online records. Some sites present data for high and low temperature, relative humidity, rainfall and snowfall, and hours of daylight. Most measures are lumped into monthly averages, which is normally adequate for cemetery preservation projects. Examples of available data include the annual climate averages for Ternopil (Ternopil oblast) on Weather Atlas, and a very useful 10-year graphical presentation of data for Nadvirna (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast) on World Weather Online, which shows the unusually high snowfall and rainfall experienced regionally in winter and spring of 2019.

Creeks and rivers: Surface and groundwater flow can have both beneficial and harmful impacts on burial sites and on preservation projects. Some project plans require temporary water sources for construction, others need long-term sources to support plantings and permanent vegetation. At a minimum, it is important to observe normal rainfall drainage paths and patterns in and around the burial site, to prevent erosion within the burial grounds and for disaster planning. For example, drainage issues and standing water in the Jewish cemeteries of Berehove and Sasovo (Zakarpattia oblast) would require correction or mitigation before other projects can successfully proceed, and any preservation project at the Jewish cemetery of Skole (Lviv oblast) would need to consider the natural and man-made drainage channels adjacent to the cemetery which route rainfall from the mountains above the site.

Roads running around and through the Jewish cemetery of Mizhhiria (Zakarpattia oblast). Image © HERE WeGo.

Roads, paths, and accessibility: Some Jewish cemeteries in western Ukraine are not near to paved or unpaved roads, but most are, and the proximity of roads affects both the accessibility of the sites for visitors and preservation project work and the risks of inappropriate development. Some information about nearby roads and paths is usually visible in online satellite images, but a walking survey is normally needed to understand not only the feasibility of vehicle passage on the roadways but also the normal local patterns of traffic. Across western Ukraine and especially in more rural areas, horse-drawn wagons are commonly used by farmers and others; these vehicles can and do navigate barely-visible roads to move goods and people, collect firewood, etc. Some of these unpaved roads cross Jewish cemeteries since WWII, especially where there are no longer signs of the cemetery’s original purpose.

Footpaths also commonly cross Jewish cemeteries in the region, and particularly when the cemeteries are located in residential areas those footpaths may be important communication paths for local people to travel from their homes to the town or village center, churches, etc. These issues will need consideration in any project plans for fencing or other obstructions; see for example project case study 12 on this website. Similarly, accessibility options for visitors to the burial site should be incorporated into concepts and plans for a site, so that elderly and disabled visitors may find suitable ways to enter and exit the site.

Utilities: In general, projects at Jewish cemeteries and mass graves in western Ukraine should plan for sustainable maintenance and security without access to local utility services (water, sewer, electricity, etc.), although temporary access may be useful during the project preparation and implementation phases. However, a survey of utility service connections in the vicinity of the burial site (as well as within the boundaries of the site, see above) may identify both opportunities and risks for future projects.

Waste materials and garbage: Open land (as many Jewish burial sites in the region appear to be) often accumulate garbage, waste building materials, and other objects in towns and villages of western Ukraine. Spaces which can be used for gatherings and recreation (barbecues, drinking, etc.) often accumulate bottles and other trash. Although these materials are deposited within the burial site boundaries, it can be useful to understand how they arrived at the site: thrown over the fence, dropped while passing through on foot, or left behind after a picnic or other gathering. Collection and disposal of garbage and construction waste from in and around burial sites is an ongoing project sustaining requirement. Learning about the accumulation process can support discussions with local authorities, schools, etc. to promote reducing, if not eliminating, the chronic problem.

Neighboring residents and businesses: Long-term residential and commercial neighbors of Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine often view themselves as stakeholders of the sites, for preserving the local history and for how the sites are viewed and cared for by themselves and others. Recent neighbors may have less knowledge about and weaker connections to cemeteries and mass graves, but it is very common to visit and spend time at a Jewish burial site in the region and then be approached by a neighbor, who may have information to share.

Many smaller towns and villages have one or more resident local historians who have monitored and taught about the area’s burial sites for decades, and both they and site neighbors sometimes take a further interest in the site, doing small maintenance tasks and leaving commemorative candles or flowers as they do at their own cemeteries and memorialized spaces.

Some neighbors may take an income interest in the sites, especially at cemeteries, by using them for informal grazing (e.g. chickens and some larger animals), gardening, or for storage of materials or vehicles. On the other hand, both residential and business neighbors often keep watch on Jewish burial sites as an aspect of local security, which can be a significant long-term benefit to site preservation and project longevity. Meeting cemetery and mass grave neighbors while conducting walkover surveys and investigating the surroundings is an important way to gauge the relationship between local people and the site, and to avoid unknowingly disturbing or offending the same people who may be willing to help. Exchanging contact information can help keep a connection remotely over time, so that neighbors can alert project leaders about unseen issues, and project leads can arrange meetings in the area with interested local people.