![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Introduction

This page presents answers to common questions which arise when people first consider projects to care for Jewish cemeteries and mass graves in western Ukraine (and elsewhere). Some of the questions indicate cultural concerns, for example to promote partnerships between local Ukrainians and foreign Jews to strengthen the joint civil and national responsibility for the shared heritage these Jewish burial sites represent. Other questions indicate practical concerns, mostly about how to start a project and how to support one.

This website is intended for use by activists with a variety of cultural and educational backgrounds, and with a range of physical capabilities. It is not surprising, however, that most of the questions listed here could come from any of this variety of people who are first considering how to help at one or more burial sites; everyone has similar questions at the beginning of a project. A desire to learn is a strong indicator of a willingness to reach out a real or virtual hand to others, and is also an excellent starting point.

No doubt there are other important questions which are not listed here and perhaps are not well answered elsewhere on this website. If you have other questions, please contact the authors of this site and we will attempt to provide a useful response.

Questions and Answers:

The Jewish burial site I intend to care for is not in the region which this website calls “western Ukraine”. How applicable is the information here to my planned work?

The matzevah shapes are different but the issues are the same in the Jewish cemetery of Shepetivka (Khmelnytskyi oblast). Photo © RJH.

Only the tabulated data and links to information about individual Jewish cemeteries and mass grave sites are specifically limited to the three eastern Galician oblasts which we call western Ukraine (Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil). The German wartime destruction of Jewish lives and Jewish cultural heritage was especially intense in western Ukraine, and postwar Soviet policies here contributed to further erasure of Jewish cemeteries and mass graves as they did elsewhere in the Soviet sphere, but the current fragile situation of these heritage sites in western Ukraine is not unique in central and eastern Europe.

The best practices guide section here can inform new burial site preservation projects across a broad range of Europe and potentially even in the Americas; project leaders will be able to review the guide material and select those parts which best apply to their local work and environments (cultural, economic, legal, climatic, etc.).

The same preservation tools and techniques useful in western Ukraine would help in this Jewish cemetery in Dubăsari, in Transnistria. Photo © RJH.

The large number of reference books, articles, websites, and videos presented here apply to heritage preservation projects almost anywhere, and in fact most of the reference materials were sourced globally for this website.

Although the case studies summarized here are intentionally drawn from example projects (and problems) in western Ukraine, every case study page includes examples from outside the region, including the rest of Ukraine and across Europe.

It is likely that every cemetery preservation volunteer or project leader will discover that there are few resources tailored to the regional and cultural issues specific to their site; as is seen throughout this website, adaptation is a key guiding principle.

I want to help care for a non-Jewish cemetery in east-central Europe. Is the information on this website applicable only to Jewish cemeteries?

A fallen cross-shaped grave marker in the historic Roman Catholic cemetery of Muzhylovychi

in western Ukraine, before cemetery preservation work began. Photo © RJH.

Not at all. A small number of important aspects of Jewish tradition and religious law (halakha) are uniquely applicable to the features of and practical work at Jewish burial sites; these are discussed in some detail on the guide page for surveys and in some of the references for surveys. Jewish burial and memorial traditions are also discussed at length in some of the references for preservation project concepts.

However, the majority of the information, recommendations, and advice in the guide section could apply equally to cemeteries dedicated to any faith and to municipal cemeteries as well. The heightened risk to Jewish cemeteries in western Ukraine due to the near-complete absence of Jewish communities to care for them, the same concerns and approaches described here apply as well to burial grounds of other displaced or transient communities, e.g. Boyko and Lemko cemeteries in southeastern Poland, and World War I soldiers’ cemeteries across the former Eastern Front. With small and often easy adjustments, much of the material on this website which is written for Jewish wartime mass graves can apply as well to so-called fraternal graves of victim groups killed in any 20th-century conflict in the region, including the Romani and many different resistant and nationalist groups, especially during and after World War II.

The challenges of burial site care are quite common across individual sites regardless of their associated communities; there is never enough funding to support the desired work, and many issues cannot be resolved simply by bringing funding. The guide page for surveys highlights some key points applicable to appreciating a cemetery and its environment; listed last but perhaps primary in importance is learning about the burial site in its specific setting, i.e. who are its neighbors and how do they interact with the site? The answer to this question is often the bridge to effective long-term care of the site.

Headstone repair and resetting in the Lemko cemetery of Małastów in southeastern Poland by the heritage NGO Stowarzyszenie Magurycz. Photo © RJH.

How can I find out where the Jewish burial sites are in my city, town, or village?

A snapshot of the Jewish burial sites map. Click on the image to navigate to the sites table overview (and an interactive version of the map).

For places in the region defined here as western Ukraine, all Jewish cemeteries and mass graves which are publicly documented and geo-located are tabulated with GPS coordinates, map links, and more in the Cemeteries section of this website; there is a separate table for each of the provincial regions: Lviv oblast, Ivano-Frankivsk oblast, and Ternopil oblast. If you know the approximate geographic location of your town or village, you can use the interactive map near the bottom of the cemeteries overview page to browse all cemeteries and known mass graves near that location, use the color coding to identify the relevant oblast, and then refer to the specific oblast page for more information.

Note that to facilitate map searches as well as partnerships with local civil administrations, volunteers, and activists, the cemetery tables identify towns and villages using the Ukrainian national English transliteration rules for the modern legal Ukrainian place names. Thus, the capital city of the Lviv oblast is listed as Lviv (not L’viv, Lvov, Lwów, Lemberg, or Lemberik). To learn the modern Ukrainian version of a historical place name which may come from another language or from family lore, Wikipedia is quite useful as a search engine, and the “town finders” on family history websites such as Gesher Galicia and JewishGen can serve as intermediaries.

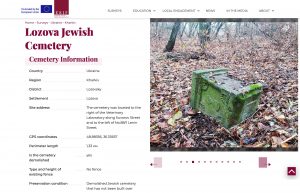

The ESJF database page for the remote and erased Jewish cemetery of Lozova (Kharkiv oblast).

Images @ ESJF.

Outside of these three oblasts referred to here as western Ukraine, two resources described on the cemeteries overview page are particularly helpful. For cemeteries, the ESJF European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative is well underway to surveying more than 3000 Jewish cemeteries in nine European countries, and its database is searchable by country, administrative division, and place name; surveyed cemeteries are represented by descriptions, GPS coordinates, and photographs. For WWII Jewish mass grave sites, Yahad – In Unum has documented and mapped locations in seven former Soviet states from historical research, site visits, and witness interviews; where public information is limited, Yahad can be contacted for more detailed data from their research.

Increasingly, the crowd-sourced media database Wikimedia Commons is collecting images licensed under Creative Commons into searchable categories including by type (e.g. Jewish cemetery) and by place (e.g. Buchach in the Ternopil oblast); either path can lead to a collection of images of the Jewish cemetery in Buchach or the less well-known mass grave sites in Rohatyn (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast). Identifying precise geographical locations from Commons media can often be difficult, but sometimes image descriptions, metadata, or links will include GPS info, and if not the images can be used to query local people based on visual context.

Additional information is sometimes available from the local or regional civic administrations (mayors and governors) relevant to the places of interest. Local history museum staffs have gathered information from documents, memoirs, local historians, and elders in their area, and may also be able to help.

I don’t know anything about this kind of work. I would like to help, even just with money, but I don’t understand the issues and the technical aspects. How can I study some, to better appreciate what can or should be done?

People come to these topics with widely varying backgrounds and motivations, but few people initially come well-prepared for the complex reality of Jewish heritage in 21st-century Ukraine. Effective site engagement requires exposure, study, and experience, plus asking lot of questions. This website includes nearly 1000 images to help illustrate the breadth of issues and approaches relevant to preserving Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine, so simply browsing the website is one way to gain some understanding of the work. Specific sections and pages of the website can help to bring focus on aspects of the work which may resonate with new activists and volunteers:

-

The tables and maps of Jewish cemeteries and mass graves in the region, which include links to external data and images published by partner organizations, can quickly provide an overview of the scope of the subject overall plus hundreds of examples of unique individual sites with their challenges and progress. For some new activists, a personal connection with a site or with a specific type of challenge may create the “hook” to spur further study and engagement.

- The “self-evaluation” section of the guide page to project concepts on this website may encourage a process of reflection to better understand personal motivations for getting involved in heritage work, and perhaps provide context for assessing the needs of individual Jewish cemeteries and mass grave sites. Overall the guide page introduces many of the questions and concerns associated with Jewish heritage preservation in a region devastated by the Holocaust and post-war Soviet policies, as well as ways to conceptualize new or sustaining projects and to identify partners and resources to support the work.

-

An image from case study 06 on a project to seasonally clear vegetation at the Jewish cemetery

and the forest mass grave monument of Bolekhiv. Photo © RJH.The case studies of past and current example projects each provide a brief but full summary of how one organization or group of volunteers approached a Jewish burial site concern, what issues they encountered, and the details of their work (including costs in many cases). Reading one or several of these examples can quickly give a close view of real heritage project work not only in western Ukraine but also elsewhere in Europe, to see how theory is put into practice in response to a variety of challenges.

- The overview to the guide section divides the broad range of preservation projects into a typical set of sub-projects which tackle one or more common concerns and goals, from surveying a site, to clearing wild vegetation, constructing fences or memorial monuments, and erecting signs, as well as intangible aspects such as planning for long-term care and maintenance of a site, to attracting volunteers and funding, and the importance of communicating about the site and the project to local and international audiences. Each of these topics is covered in depth on individual guide pages which are heavily illustrated with examples of problems and possible solutions.

-

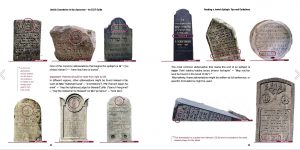

Illustrated text on tips for reading a Jewish epitaph from the ESJF classroom guide to Jewish cemeteries. Images © ESJF.

Each of the pages on print and digital references includes one or more key books, articles, or websites which can provide an expert overview to a specific topic in a few pages, or a few hundred. Although Jewish heritage preservation in western Ukraine presents some particular challenges, nearly every element of the work has already been addressed in related projects somewhere in the world. (Much of the reference material has been published in English, which presents a challenge for local heritage and civil society activists in Ukraine, but generally these activists are resourceful when it comes to using foreign-sourced materials.) For example, the references page on project concepts includes three useful introductions to this type of work: ESJF’s “Jewish Cemeteries in the Classroom“, which provides educators (and students) with strategies for creating and strengthening cultural connections with Jewish cemeteries, including researching history and documenting headstones; Lynette Strangstad’s “A Graveyard Preservation Primer“, which has a North America focus but provides very practical advice for overall cemetery care including stone conservation; and Caitlin DeSilvey’s “Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving“, which encourages taking a step back and a broad perspective view before committing to a heritage preservation plan which will require a heavy ongoing commitment of time and resources to maintain.

-

There is useful work for a wide range of skills and knowledge, and much can be learned on the job. Photos © RJH.

Joining a project as a local or remote volunteer is one of the best ways to gain exposure and experience, to learn about issues, methods, and tools, to train eyes and hands in practical work, and to better appreciate the cultural dimensions of both Jewish burial sites and local environments. The authors of this website joined a dozen different one-day and multi-day projects at Jewish and Christian cemeteries in Poland on site clean-up, headstone resetting and repair, fence maintenance, plus communication and funding, before and after they began organizing their own projects in western Ukraine; they continue to join cemetery and mass grave projects based in Lviv and other western Ukraine towns in a self-guided informal learning process. Hands-on learning at burial sites isn’t possible for everyone; contacting project leaders will usually create opportunities for alternate ways to help and learn.

I am a resident of a town which has a Jewish cemetery (or mass grave), and the site is in bad condition. How can I find resources to do something to help?

A city official collaborating with a Jewish religious representative to recover and reset headstones in the Jewish cemetery of Zaliztsi. Photo © Vasyl Ilchyshyn.

Jewish cemeteries and mass graves are shared heritage; the responsibilities and the cultural benefits of preserving and enhancing these sites belong both to the local resident civil community and to the descendants of the Jewish families who are buried there. Long-term partnerships between municipal authorities, regional civil society organizations, regional Jewish communities (where they exist), and foreign descendants of Jews from the place, are important to ensure a sustainable approach to managing the sites; both formal and informal (e.g. social media) connections are valuable. As a local resident, the first contacts should be with the municipal authorities (the town or village council) and with local civic project organizations – those who organize volunteer events to care for other public sites in the area (which may include civil groundskeeping services, the Plast or other scouting groups, etc.). With some local civic commitment to try to care for the site, then the guide page to project support and funding on this website outlines a number of other opportunities to find and secure resources to enable joint efforts, including volunteers, grants, and donations. A key resource will likely be Jewish descendants, who normally have a personal and family stake in the care of these places, and for some, a religious responsibility as well. A careful and complete review of the guide page should enable a comprehensive strategy to address the local concern.

I have seen photos of the Jewish cemetery (or mass grave) where my family is buried, and the site is in bad condition. How can I find resources to do something to help?

Part of a volunteer clearing crew – Jewish, Ukrainian, other European, and American – in the Jewish cemetery of Rohatyn. Photo © RJH.

Many Jewish descendants of families who once lived in what is now western Ukraine have made significant progress in caring for their families’ burial sites by creating or joining groups with others whose families originated in the same place (or nearby). Jewish genealogy organizations such as JewishGen and Gesher Galicia promote online connections to virtual “kehilas” or “shtetl” groups for discussion about shared family history, which can be extended in many cases to the care of shared family material heritage. Organizing as a group can amplify communication of status and data, generate ideas and project concepts, and increase the strength of commitments of materials, tools, and funding for site work. As a group with defined leadership and contact info, it is also easier to form long-term partnerships with municipal authorities for identified projects and routine maintenance at burial sites. The guide page to project support and funding on this website outlines not only the variety of partnership opportunities but also many other ways to identify and secure support for proposed projects. Communication cannot be over-emphasized, both via traditional media and by less-formal social media.

Where in western Ukraine have projects similar to what I am considering been completed, or started?

Vegetation clearing at the dilapidated mass grave memorial near Rudky. Photos © RJH.

The known projects page on this website tabulates more than 150 cemeteries and mass graves in the region which have had or currently have active projects managed by one or many people and organizations. Nine categories of projects are marked in the tables with symbols to indicate current/completed status vs. projects in planning stages; many of the sites have or have had more than one different project category, and a few have had four or more different projects at the same location.

Not many cemetery preservation projects in western Ukraine have had or still have webpages or websites which document the work, but for most of the tabulated sites on the known projects page, at least an image or some other public evidence of the project is linked to the table row. In some cases the originator (an individual or an organization) of the information is still active in documentation or preservation work, and may be contacted for additional images or information.

How can I see examples of current or recent projects like what I am considering?

A completed full perimeter fence and gate project at the Jewish cemetery of Busk. Photo © ESJF.

Summaries of twenty example projects in western Ukraine are available in the case studies section of this website listed by intangible (documentation or communication only) vs. tangible (physical projects); some people may prefer a more matrixed listing of the projects. Each individual case study page is illustrated with photos of the project, sometimes including the work in progress as well as the result. The format of the case studies pages includes a description of the site with its GPS coordinates, site ownership (where known) plus stakeholders, and a list of other projects at the same site. Analysis of each project includes a history of the site and a summary of its current features, followed by details of the project, a review of issues encountered, an outline of the project costs, and known residual risks to the site preservation. A handful of similar projects are then listed and linked for further study, including both projects in western Ukraine and some outside the regional scope of this website. The project summaries conclude with a linked list of external references which further describe the site and the project.

News about current cemetery clearing projects on the Jewish Heritage Europe website and in their Facebook group.

Beyond the project examples illustrated and linked here, browsing or searching news articles on the Jewish Heritage Europe web portal can give a much broader range of burial site project information covering all of Europe. Project data and other info can also be searched by country, and there is also a dedicated cemeteries section on the website with a projects and preservation subsection listing international and country-specific organizations active in burial site heritage work.

Less formally but often more dynamically, heritage-focused social media pages and groups can also provide news and information about cemetery projects and the activists involved. These sources are somewhat transient, but currently-useful examples include the Facebook entities JHE – The Jewish Heritage Europe Group (associated with the web portal described above), International Survey of Jewish Monuments (ISJM), more general groups such as Cemetery Preservation and Restoration, as well as the social media pages of any of the regional and international expert organizations listed on this website as well as the pages of this website’s contributors.

How can I support regional civil society and heritage activists, and local city and school authorities, in their efforts to rehabilitate Jewish heritage in the area where my family is from?

The Lviv Volunteer Center (LVC) leads other volunteers and civil society activists in a major Jewish headstone recovery project on an urban street in Lviv. Photo © RJH.

There are a few key ways to support local and regional activity in the care and preservation of Jewish cemeteries and mass graves. One important method is public promotion of the work in a variety of local and international media, from newspapers to social media, through sponsored television and other video coverage, in presentations to Jewish cultural and genealogy organizations, on dedicated static websites for projects, etc.; including contact information for project leaders and the other methods described in the guide page to communication strategies on this website can make the work discoverable to others who want to help. Another approach is through direct funding for materials, expert services, labor, and machinery; often it is difficult to transfer money into Ukraine to support individual leaders and small organizations, so a review of the options and issues on the guide page for support and funding is advised. Another option, which is financially inefficient for the project but can be very valuable in creating long-term partnerships, is to travel to the area to join a locally-managed volunteer event; anyone considering this option should bear all of their own travel planning and expenses, and should carefully minimize their need for language translation and other handling while onsite, but the presence of a Jewish descendant working hand-in-hand with others can have a powerful effect on cultural relations and practical work during and after the event. Contact the activists and authorities to ask them what they most need to support their work, and how best you can help from afar or onsite.