![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Introduction

This page summarizes and analyzes a multi-day project which collected displaced Jewish headstones from under a single street in Lviv, a city of oblast significance and the administrative center of the Lviv oblast in western Ukraine, and transported them for safekeeping to the new Jewish cemetery in the city. The project was conducted with both formal and informal aspects by a large number of volunteers over a period of about two weeks, resulting in the recovery of 125 headstones and large fragments. Although there are concepts and plans to conserve and document the headstones and incorporate them into a memorial at the new cemetery site, this project summary focuses primarily on their recovery and return.

This page is intended as a reference for similar projects now in the planning stages in western Ukraine or beyond. Following a brief summary of the site, the material below describes the project and reviews its effectiveness together with a listing of issues encountered, approximate project costs, and ongoing risks. Related projects both in western Ukraine and elsewhere in Europe are also briefly mentioned, for comparison. At the bottom of this page are links to project documentation and to additional reference information about the burial site and related projects.

Read the overview to case studies of selected projects at Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine.

Project Summary

Two views of Barvinok Street in June 2018, after the city scraped the street surface but before the recovery project began. Photos © RJH.

Project type: Identification, recovery, and return of Jewish headstones which were taken from at least one Jewish cemetery and misused as building materials during WWII.

Location and site type: The headstones were discovered under Hanna Barvinok street in the Franko district of Lviv, about 2.5km southwest of the city center; GPS: 49.82855, 24.00335. The return point (and likely historical origin) of the headstones is the new Jewish cemetery of Lviv, Ukraine; GPS: 49.85087, 24.00214.

Description of the site: Barvinok Street is an asphalt-paved road in a primarily residential district with high apartment buildings from the Soviet-era and later, plus courtyards, a preschool, etc. The overall length of the street is about 200m; the portion excavated for the headstone recovery work is about 30m long by 6m wide, and mostly level.

Ownership and stakeholders: The street is under the authority of the city of Lviv, with local management by the Franko district administration. Stakeholders include the municipal authorities, local residents and businesses, the Jewish community of Lviv, foreign descendants of Lviv’s pre-war Jewish and other families, historians, and students of Jewish culture.

Official heritage status: None.

Activists working on/at the site: Project organization and daily management was by the Lviv Volunteer Center (LVC), a non-profit organization based in Lviv and working under the Hesed-Arieh All-Ukrainian Jewish Charitable Foundation, with overall leadership by the LVC director Sasha Nazar; contact info is available via Facebook and the Hesed website. Joining the LVC as volunteers on most work days were community leaders affiliated with St. Anthony Catholic Church in Lviv, professors and staff of Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv, Rohatyn Jewish Heritage, as well as journalists and more than a dozen other individual volunteers.

Other projects active at the site: Headstones have also been uncovered and recovered from other sites in the immediate vicinity of Barvinok Street, both before and after the project summarized here, including on the grounds of the preschool and behind an abandoned house on Konotopska Street, one block away (see below for more information). Those recovered headstones were also moved to the new Jewish cemetery in Lviv for safekeeping.

Project Analysis

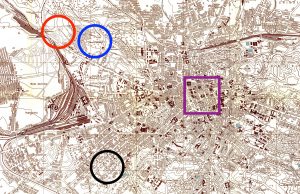

A 1941 German map of Lviv, copied from a Polish original. Highlighted are the old city center (violet square),

the new Jewish cemetery (blue circle), the future Janowska concentration camp (red circle), and Pod Stoczkiem Street (future Barvinok Street). Map image courtesy Harrie Teunissen and John Steegh via Gesher Galicia.

History of the site: According to a Wikipedia article, the street now named for Hanna Barvinok was established in Lviv’s “Nowy Świat” (New World) expansion district in the early 20th century. A Polish street map of Lwów from 1920 shows the street was still unpaved at the time even though a light rail line crossed it at one end. The “Lviv Streets” project of the Center for Urban History of East Central Europe documents the first name of the street as Pod Stoczkiem (roughly “foot of the slope” in Polish), from 1916 to 1942, and this is the name shown on a 1941 German street map of Lemberg copied from a Polish original developed as part of the Third Reich’s plans to occupy Poland. For two years during the German occupation, the street was named Fritz Weitzelgasse in honor of a Nazi party official and SS-Obergruppenführer who had died in an aerial raid on Düsseldorf in 1940. Following Germany’s retreat from Distrikt Galizien in 1944, the street name was briefly returned to Pod Stoczkiem before taking its present name in honor of Hanna Barvinok, pseudonym of the 19th-century Ukrainian writer Oleksandra Mykhailivna Bilozerska-Kulish.

An image from the 1943 Katzmann Report describing Jewish headstones in Lviv

as road-building materials. Image via IPN.

Local residents interviewed while the headstone recovery project progressed stated that during the German occupation of Lviv there was a military radio station as well as the residences of several high-ranking German officials in the neighborhood, which may have justified the reinforcement of the street foundation with the stone slabs of Jewish cemetery markers at that time. A local historian speculated based on similar actions elsewhere that the labor to uproot the headstones from the cemetery and transport them to this street location was likely forced upon Jewish inmates of the Yanovska concentration camp located a few hundred meters from the new Jewish cemetery, northwest of central Lviv. Based on the epitaph dates of the recovered headstones and the recorded closure of Lviv’s large old Jewish cemetery in the 19th century, all of the recovered headstones were almost certainly stripped from the new Jewish cemetery, about 2.5km north of Barvinok street. The removal of headstones from Jewish cemeteries in Lviv was documented by the German occupying force itself, for example in the infamous Katzmann Report of 1943, as was the use of forced Jewish labor for roadworks.

Current features of/at the site: Several long-term residents of Barvinok Street reported sightings of Jewish headstones under the street surface when the city and/or utility companies excavated portions to access underground piping, wiring, etc. According to these witnesses, in some cases the headstones were replaced under the street when the repairs were completed, and in other cases the headstones were recognized as inappropriate building material and were left at the side of the road. In 2008, a small number of Jewish headstones were extracted, but their fate is unknown now; others found in 2010 were taken to the new Jewish cemetery. In the summer of 2017, new underground repairs uncovered about a dozen large Jewish headstones and fragments, which were set to the side of the street when the excavation holes were filled; these stones were collected by the Lviv Volunteer Center and taken to the new Jewish cemetery, but the site was also marked by the LVC for future research.

Details of the project: Surface scraping for new asphalting by the city began on Barvinok Street in mid-June of 2018, exposing but not extracting dozens of Jewish headstones close to the excavation point from 2017; local residents notified the Lviv Volunteer Center about the discovery. This time, the LVC organized to bring volunteers and attempt to recover some of the embedded headstones, with flat shovels, large pry bars, and other hand tools.

Only a handful of stones could be removed on the first day, so the LVC made a call via Facebook and telephones to a wider group of volunteers, and many more showed up over the next days. Intermittent rain and exhaustion forced a staggered work schedule, but on each work day more tools and more hands arrived, as well as additional support from residents of the street, holding the city’s road work at bay while the recovery continued.

On the last day of work, donations requested through a spontaneous social media campaign allowed the LVC to hire a large road-working machine to accelerate the excavation and moving of the heavy stones to the sidewalk of the street, and then replacement of gravel and other road materials into the large shallow pit left from the extraction, smoothing the surface to make it navigable until the city’s road works could be completed.

Some days later, a large flatbed truck with hydraulic lift was hired to move the numerous pallets of recovered headstones to the new Jewish cemetery. A subsequent volunteer work camp organized by the LVC the following year sorted and cleaned the recovered headstones to prepare them for long-term storage at the cemetery until a new monument can be constructed using the headstones as memorial elements.

In all, 125 Jewish headstones and large fragments were counted as recovered from under Barvinok Street in 2018, most of them intact at least on the front (epitaph) face.

Issues encountered in the project: Although the city did not interfere with the volunteer work, it did not support it either, and much of the hard work was thus performed by hand, including lifting and moving the heavy stones (some of which weighed more than 300kg). Intermittent rain and the slow work meant that the street was torn open for more days than had been hoped, creating an inconvenience to drivers in the neighborhood, some of whom became angry with the project leaders, though other neighbors offered to help in small ways, including providing an electricity connection for a jackhammer and a storage place overnight for tools. A few of the volunteers suffered scrapes and cuts to hands, arms, and legs during the work, though none were serious, and nearly every volunteer suffered strains and sore muscles from moving heavy materials around during the project.

Also slowing the work was the care the volunteers gave each headstone, working to protect the faces and edges of the stones as much as possible while prying them out of the ground. Some stones were fractured into hundreds of pieces and could not be saved intact. Others appeared to have lost their inset plaques even before they were installed under the road surface during the war. Several handfuls of epitaph fragments were found, each with only one or two letters or numbers. Every one of the volunteers celebrated when a large stone was turned over to find that the carved epitaph was complete.

A wide variety of hand tools were passed from volunteer to volunteer to keep the work in constant progress. Photo © RJH.

Project costs, one-time and sustaining: All of the labor in uncovering and extracting the headstones from under the street, moving them to the side and stacking them on pallets, as well as sorting them and re-stacking them at the cemetery, was provided by unpaid volunteers, totalling more than 600 person-hours of labor by dozens of individuals. Most of the volunteers were resident Ukrainians from the Lviv region, but some came to help from around Ukraine, and there were several international volunteers resident in or passing through Lviv, as well as visitors from Poland and other countries who heard about the effort and came to lend a hand.

Many of the announcements and calls for help were raised on social media platforms and on an informal communication network within the Lviv Volunteer Center. Likewise, requests for donations to cover both the small costs of tools and supplies, as well as the major costs of the heavy machinery used to accelerate the work on the last day of recovery plus the transport and unloading of the headstones, were spread through large and loosely-organized social network groups, especially on Facebook. Many volunteers brought their own gloves and shared water, coffee, and cookies with others.

The LVC brought hand tools for extracting the stones (square-blade shovels, brooms, a pick, several large pry bars, an electric jackhammer, etc.) and both steel hooks and woven-nylon straps for lifting the stones; other groups including Rohatyn Jewish Heritage and the Catholic organizations brought additional tools of most of these types plus buckets and lifting hooks, so no new tool purchases were needed except for gloves, trash bags, etc. Electricity to power the jackhammer was provided for US$4 per day during two days. Wooden pallets and sticks for stacking and separating the headstones were provided by the LVC from existing stock at the Vuhilna Street (Jakob Glanzer) synagogue and additional pallets were gathered on the work days; car rental to deliver the pallets to the work site was US$26. For additional information about tools used in this and similar projects, see the review of tools for recovering and transporting displaced headstones on this website.

The hydraulic machinery and truck costs were approximately as follows: about US$18 per hour over 10 hours spanning 2 days, including transport to the site, for the backhoe to extract and move headstones; about US$20 per hour over 15 hours spanning two days for one truck-mounted hydraulic lift for gathering and moving the loaded pallets to the new cemetery, and then unloading them; about US$88 for one day use of a small manipulator to gather the residual blank headstone fragments at the roadside and transport those to the cemetery as well. All out-of-pocket costs (not counting volunteer time) totaled just over US$600.

Current risks to preservation: To date only about 20% of Barvinok Street has been excavated to recover Jewish headstones serving as structural roadbed. When the project which is summarized here had ended and before the street was closed again, additional headstones were visible at the edge of the adjacent section of the street, and some local residents believe the entire street may be built on Jewish headstones. Other recoveries in the neighborhood suggest that surplus headstones from the original wartime theft and road-building, or stones encountered in occasional postwar roadwork, may continue to be found in the courtyards, gardens, and service buildings in the area.

Many of the headstones extracted during this project were originally carved from pink sandstone; the long-term bending stress of vehicles passing over them caused the stones to split along sedimentary planes, so that the stones fell into multiple sheets as they were lifted by hand or machine. In most cases the faces of these headstones could be preserved intact, but the thin stone sheets are especially fragile in handling and transport.

The new Jewish cemetery in Lviv continued to suffer damage after WWII, during the Soviet period, and some lesser security threats may still be present. The recovered headstones will be at some risk of further damage until they and future recovered stones can be incorporated into a permanent memorial at the site.

Three views from a street intersection after the extraction work stopped: looking back at the work section, down the intersecting Kvitneva Street, and forward at the undisturbed portion of Barvinok. Photos © RJH.

International volunteers recover Jewish headstones from behind a house on Konotopska Street in Lviv. Photos © RJH.

Related projects in western Ukraine: Two other Jewish headstone recovery projects in western Ukraine are summarized in case study 07 (around Rohatyn in Ivano-Frankivsk oblast) and case study 11 (from two sites in the village center in Zaliztsi in Ternopil oblast) on this website. In the city of Lviv, the LVC has also organized the recovery of Jewish headstones from a stairway in a city center building courtyard, and from a retaining wall behind an abandoned building on a street parallel to Barvinok Street and only one block away. In both cases, the extraction and transfer work was done entirely by hand. Both of the other case studies linked include additional examples of regional headstone recovery and return projects.

Related projects outside western Ukraine: Extending the history of the damaged Užupis Jewish cemetery in Vilnius, Lithuania described in case study 07, additional headstone fragments were recovered from a hospital site in the city and returned to the cemetery in 2016, and from the stairway to a church in 2019. In 2020, multiple reports were filed about the recovery of over a hundred Jewish headstones extracted from under the large market square in Leżajsk, Poland. Ongoing news developments about Jewish headstone recoveries can be found by searching the news section of the Jewish Heritage Europe web portal with keywords such as “headstone recovery”, “fragments”, etc.

References

-

Rozwiązanie kwestii żydowskiej w Dystrykcie Galicja (“Lösung der Judenfrage im Distrikt Galizien”, or “Solving the Jewish Question in the Galicia District”) – Instytut Pamieci Narodowej (IPN); prepared by Andrzej Żbikowski; Warszawa, 2001.

- East of Lviv Through Galicia – a photo and text essay from 2017 covering headstones uncovered on Barvinok Street as well as Jewish heritage at sites northeast of Lviv, from Christian Herrmann’s Vanished World blog site

- Facebook post dated 18Jun2018 – on the start of the new headstone recovery project, posted by the Lviv Volunteer Center – ВЄБФ “Хесед-Ар’є”

- Facebook post 21Jun2018 – on the project in progress, posted by the Lviv Volunteer Center – ВЄБФ “Хесед-Ар’є”

- Facebook post 21Jun2018 – on the project in progress, posted by Marla Raucher Osborn of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage

- Facebook post 25Jun2018 – on the project in progress, posted by the Lviv Volunteer Center – ВЄБФ “Хесед-Ар’є”

- Facebook post 25Jun2018 – on the project in progress, posted by Marla Raucher Osborn of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage

-

Facebook post 26Jun2018 – a call to volunteer action, posted by Marla Raucher Osborn of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage

- Facebook post 28Jun2018 – on the project in progress, posted by Marla Raucher Osborn of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage

- Facebook post 28Jun2018 – 3-minute video of volunteers extracting and moving a headstone from the street, posted by documentary filmmaker Sashko Balabai

- Facebook post 02Jul2018 – on the arrangement for heavy machinery to help accelerate the project progress, posted by the Lviv Volunteer Center – ВЄБФ “Хесед-Ар’є”

- Facebook post 02Jul2018 – on the project in progress, posted by Marla Raucher Osborn of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage

- Facebook post 17Jul2018 – on the collection and transfer of the recovered headstones to the new Jewish cemetery in Lviv, posted by the Lviv Volunteer Center – ВЄБФ “Хесед-Ар’є”

-

Facebook post 17Jul2018 – on the collection and transfer of the recovered headstones to the new Jewish cemetery in Lviv, posted by Marla Raucher Osborn of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage

- Facebook post 27Mar2019 – on the collection of residual broken and unmarked fragments of headstones from Barvinok Street and their delivery to the new Jewish cemetery in Lviv, posted by the Lviv Volunteer Center – ВЄБФ “Хесед-Ар’є”

- Facebook post 16Aug2019 – on the sorting, cleaning, and storing of the recovered Barvinok Street headstones at the new Jewish cemetery in Lviv as part of a large volunteer work camp, posted by the Lviv Volunteer Center – ВЄБФ “Хесед-Ар’є”

- Gator som bär sår (“The streets bear their wounds”) – an essay in five parts (see also Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and the concluding Part 5) by headstone recovery volunteer Sonia Engström for her viewpoint-east.org blog

- У Львові під час ремонту дороги знайшли єврейські надгробки (“Jewish tombstones found in Lviv during road repairs”) – news video coverage of the headstone recovery work on Barvinok Street in progress on 25 June 2020, by Ukrainian news Channel 5

- Ukraine: Dozens of matzevot rescued from under L’viv street; had been used as paving – a summary on 26 June 2018 of real-time Facebook reports by Sasha Nazar and Marla Raucher Osborn in the news portal of Jewish Heritage Europe

-

Volunteers rescue Jewish headstones used to pave street in western Ukraine – news coverage of the recovery effort reported on 28 June 2018 by JTA (Jewish Telegraph Agency)

- Врятувати мацеви (“Saving Matzevot”) – news coverage of the recovery effort reported on 03 July 2018 by Yulia Lishchenko for Високий Замок

- «І нацисти, і радянська влада не церемонилися з єврейською історією…» (“Both the Nazis and the Soviet authorities did not respect Jewish history …”) – news coverage of the recovery effort reported on 12 July 2018 by Yulia Lishchenko for Високий Замок

- Lemberg (Lwów) General Street Map 1920 – a detailed general plan of the city from a survey during the interwar era, showing the as-yet unpaved street, from a scan databased by Repozytorium Cyfrowe Instytutów Naukowych (RCIN) and presented by Gesher Galicia

- Lemberg (Lwów) General Street Map 1941 – a detailed general plan of the city from an original Polish survey during the interwar era, then copied with German annotations by the Nazi government, from the map collection on European Jewish presence of Harrie Teunissen and John Steegh and presented by Gesher Galicia