![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Introduction

The Lviv Volunteer Center and local craftsmen repair a memorial in the Jewish cemetery of Dobromyl (Lviv oblast) during Hanukkah 2019. Photos © LVC.

Since World War II the majority of Jewish cemetery preservation projects in western Ukraine have been conceived, planned, funded, and conducted as events – that is, one-time efforts. This has been true for most common project types, including boundary surveys, site cleaning and clearing, headstone conservation and documentation, remedial landscaping, perimeter fencing, sign installation, and the erection of monuments. Organizing a burial site project as an event is understandable given the typical costs and the difficulties in coordinating resources, tools, and workers, often depending on international connections and multilingual communication. It can be difficult to effectively support a project for an entire year, or even a season; project timelines typically span finite periods with definite end dates – intentional or not.

In the absence of plans and resources to continue monitoring and care, the beneficial disruptive effect of a burial site conservation or preservation event will be transient at best, dissipating or unraveling on time scales ranging from a year to a few decades. Choices made in materials and methods on current and past projects may also complicate future conservation efforts, and in some cases may actually accelerate decay or damage at the site. Several of the guide pages on this website have pointed to the importance of considering the long term as part of most cemetery projects, especially during project concept phases.

The importance of planning ahead to return regularly to maintain Jewish burial sites is discussed and illustrated on this website on the guide page to site clearing and cleaning, and we will emphasize that concern repeatedly on this page and this website as one of several strategies essential to sustaining cemeteries and mass graves as commemorative sites. While the circumstances of the Holocaust in western Ukraine and policies of the Soviet Union across Ukraine after the war were dominant factors which determined the current condition of Jewish burial sites in the region, the very visible signs of neglect which now typify these sites and inspire new action are hardly unique across different times, geographies, and religious communities. Well before the devastation in WWII, untended cemeteries “in ruins” were the subject of paintings, photographs, and essays across Europe; many of these treatments were in romantic style, but not everyone saw beauty in decay.

The overgrown Jewish cemetery of Bibrka (Lviv oblast) before 1900. Source: Polona.

In 1924 the German-born secular Jewish novelist Alfred Döblin traveled to Poland (which at that time included most of today’s western Ukraine) to see religious Judaism first-hand, and published his book-length essay “Journey to Poland” the next year. Before visiting Lwów (Lviv) and Kraków, and although his primary focus was on Jewish life, he describes his impressions of the large Jewish cemetery on Okopowa Street in Warsaw on the day before Yom Kippur, when the cemetery is heavily visited:

[W]hen I leave the row of marble graves, the boulevard of the notables, I can no longer see anything of the burial mounds. I find a large, agitated meadow… [i]t looks wild, churned up… Now and again, something emerges from the green, a back, a head, a face… The graves are all set up in one direction, overrun with thick grass… Many people walk about, seeking, pushing apart the grass that already completely shrouds the graves. (Journey to Poland; Alfred Döblin, translated by Joachim Neugroschel; Paragon House, 1991; pp.63-65)

Grass and shrubs growing freely in the Remuh cemetery of Kraków. Source: Polona.

Döblin also visited the large Jewish cemetery in Vilnius (annexed by Poland shortly after WWI), where he notes a horse path has been informally cut among the graves as a shortcut between neighboring military barracks, and other problems:

Here, we find a vast lawn with several trees and, irregularly, here and there, alone and in clusters, low stone slabs. Withered leaves lie everywhere… Shards, stone fragments, bricks lie about. Terrible neglect of this cemetery… How dilapidated everything is here… I climb over a small rise on which shattered stone plaques are strewn. When I stand on top, I see a cow grazing below. Pasturing on the graves. Its pats lie around… The grass runs wild and high. On the mounds, you keep stepping on shattered headstones. (Ibid.; pp.111-113)

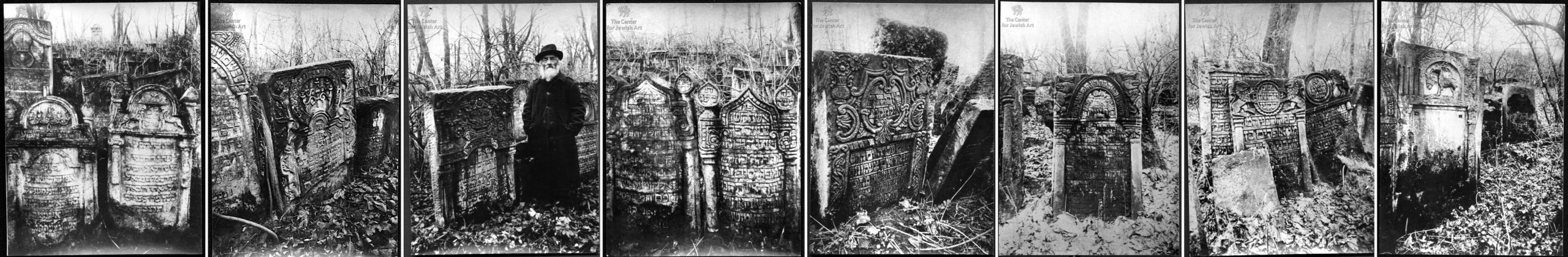

The public database of Jewish funerary art on the website of the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem includes a collection of photographs taken at the old Jewish cemetery in Lviv (erased during WWII and overbuilt in the Soviet era) which were taken by an unknown photographer in 1925. These images depict what Döblin described: beautifully carved headstones, many tangled in heavy brush and trees, with some leaning or broken. Elsewhere, a short film from 1930 of the Jewish cemetery in Kolbuszowa, Poland (only 100km from western Ukraine), now digitized and online as part of the YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, shows vines and shrubs growing under tall trees and climbing the many headstones visible as the camera pans. Similar scenes are depicted in prewar photographs of Jewish cemeteries of Kraków and of Bibrka (in the Lviv oblast of western Ukraine), on the Polona public database of the National Library of Poland. These issues are common and enduring; to address the issues, project concepts, strategies, and solutions require a long view.

Wild vegetation and disarray among the headstones in Lviv’s old Jewish cemetery ca. 1925. Source: CJA.

Sustainability has many definitions and can apply to many fields. For our purposes, we are only considering the long-term care and preservation of Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine and the individual projects which aim to achieve that preservation. Even defined this narrowly, the work involves overlapping and interconnected cultural, social, environmental, economic, political, and technological domains, with both local and international engagement and impact. Simply put, sustainability means planning for, adapting to, and managing change so that burial sites can endure and (ideally) retain their commemorative purpose beyond our own lifetimes. Several aspects of this topic are discussed in the sections below, addressing perspectives of change and time, scale, nature and culture, process, and systems.

Sustainability and Heritage Conservation: Themes and Terms

Since the 1970s, “sustainability” most often relates to balancing economic development with environmental stewardship and natural resource renewal. From about the 1990s, similar concepts began to be applied to heritage conservation (also called historic preservation), and the field of cultural sustainability began to expand. In the preface to proceedings from an ICOMOS symposium on managing change as heritage preservation practice, University of Pennsylvania conservation professor Frank Matero highlights how cultural heritage differs from resources in the building industry:

For historic tangible resources – whether cultural landscape, town, building, or work of art – the aim is notably different, as the physical resource is finite and cannot be easily regenerated. Instead, sustainability in this context means ensuring the continuing contribution of heritage to the present through the thoughtful management of change responsive to the historic environment and to the social and cultural processes that created it. By shifting the focus to perception and valuation, conservation becomes a dynamic process involving public participation, dialogue and consensus, and an understanding of the associated traditions and meanings in the creation, use, and re-creation of heritage.

The fundamental objectives of conservation concern ways of evaluating and interpreting cultural heritage for its preservation and safe guarding now and for the future. … Sustainability emphasizes the need for a long-term view. If conservation is to develop as a viable strategy, the economic dimension needs to be addressed, while at the local level community education and participation is central to sustaining conservation initiatives. … Effective heritage site management involves both knowing what is important and understanding how that importance is vulnerable to loss. … As both a means and an end, heritage conservation should provide a dynamic vehicle by which individuals and communities can explore, reinforce, interpret, and share their historical and traditional past and present, through community membership as well as through input as a professional or non-professional affiliate. (Managing Change: Sustainable Approaches to the Conservation of the Built Environment: 4th Annual US/ICOMOS International Symposium; organized by US/ICOMOS, Program in Historic Preservation of the University of Pennsylvania, and the Getty Conservation Institute; Jeanne Marie Teutonico and Frank Matero, eds.; Getty Conservation Institute Proceedings Series, 2001; pp. vii-viii. See the references on sustainability.)

The former English Heritage (Historic England) archaeologist Graham Fairclough addressed sustainability issues in cultural landscapes (both physical and conceptual) in the same ICOMOS volume:

The forest near Lysynychi (Lviv oblast), a place of modern recreation and wartime mass graves. Photo © RJH.

The cultural landscape is central to the debate about managing change. It is entirely the product of change and of the changing interplay of human and natural processes; our intellectual and spiritual responses to it are ever-changing; its components (tree cover, hedges, land cover) are semi-natural living things, changing daily and with the seasons. Change, both past and ongoing, is one of its principal attributes, fundamental to its present character. There is no question of arresting change.

Change needs to be managed, however. Conservation should not merely be change’s witness but a central part of its very process, the better to direct it sustainably. Conservation is not the “outside” activity it once was, no longer merely a fight to save fragments of the past from some body else’s bulldozer of progress.

My premise here is that conservation should seek to manage change everywhere within the historic environment, as well as to protect the “best” parts. This is a particularly necessary perspective for the cultural landscape, which is a dynamic, living set of complex systems that must have room for change if part of its character is not to be lost. But managing change should also be the objective for conserving sites and monuments. Places protected as “monuments,” set aside from everyday life and preserved for research, education, or tourism, will always be a minority. The majority of the historic environment is in every day use, and this means accepting that a consequence of continued use is continued change.

Ukrainian, American, and Polish volunteers of all ages listening to a town elder at the old Jewish cemetery in Rohatyn (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast). Photo © RJH.

This is not an argument that only economic values matter but the opposite… [t]he social, personal, environmental, emotional, or psychological benefits of caring for the historic environment are probably worth more to society than economic gains from replacing it. Nor is accepting the need for change an argument that all or any change is acceptable. For the historic environment, sustainability means controlling change and choosing directions that capitalize most effectively on the inheritance from the past. In any decision about change and about the impact of the future on the remains of the past, therefore, we should be conscious of two separate questions: (1) how to reconcile minimizing loss with the needs of the present and (2) how to ensure that the balance we strike does not reduce too greatly our successors’ options for under standing and enjoying their inheritance. What is enough to keep for our purposes? How much might the future need?

Conservation is therefore about passing on options. We cannot know what the future will want to keep, but we can seek to pass on enough to allow future generations to make their own decisions, and to not close too many doors for them. As always, however, “enough” is hard to calculate, especially in relation to the historic environment, which is all-embracing, our whole habitat, the source of our identity. Can there ever be enough? (Cultural Landscape, Sustainability, and Living with Change?; Graham Fairclough; Ibid., pp.23-46.)

An electric power transformer and utility pole on the Jewish cemetery of Yazlovets (Ternopil oblast). Photo © RJH.

In the introductory chapter of her text surveying experiments in alternative approaches to cultural heritage conservation, cultural geography professor Caitlin DeSilvey introduces the idea of collaborating with the natural processes of decay rather than attempting to oppose or reverse them:

We live in a world dense with things left behind by those who came before us, but we only single out some of these things for our attention and care. We ask certain buildings, objects, and landscapes to function as mnemonic devices, to remember the pasts that produced them, and to make these pasts available for our contemplation and concern. The language that we use when an object or structure is recognized for its potential contribution to cultural memory work immediately presumes a threat, a risk of loss. We speak of vulnerable places and things needing protection, conservation, and preservation. Action is required to restore or maintain the physical integrity of the threatened object and ensure its survival. Intervention and treatment aim to protect things from outright destruction or neglect as well as more indirect processes of erosion, weathering, decay, and decomposition. But what happens if we choose not to intervene? Can we uncouple the work of memory from the burden of material stasis? What possibilities emerge when change is embraced rather than resisted? (Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving; Caitlin DeSilvey; University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis, 2017; pp.3-4. See the references on concepts.)

Sustainability themes often complement each other, and occasionally contradict each other. In his article in the ICOMOS volume, Fairclough listed several principles important to achieving sustainable management of heritage landscapes, including increased awareness of the whole of the historic environment (beyond a single site) and of different scales (of time and place), the need for a long-term view of actions, recognizing that where possible change should be reversible, and that decisions should be informed (a precautionary approach). (Fairclough, p.27.)

In 1867, the future British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli helped grind a theme of progress into a cliché: “Change is constant.” A hundred years later, another Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, the self-declared “greatest master of clichés in the British House of Commons” extended Disraeli’s view: “He who rejects change is the architect of decay. The only human institution which rejects progress is the cemetery.” Our perspective is different, by necessity.

The impact of only three years of unchecked wild vegetation growth in the Jewish cemetery of Shchyrets (Lviv oblast): December 2016 (left) vs. December 2019 (right).

Sources: Vanished World and Rohatyn Jewish Heritage.

Cultural Changes

Jewish headstone recovery work by the Lviv Volunteer Center in summer 2020; the stones were returned

to the new cemetery in Lviv. Photos © LVC.

A cemetery rehabilitation or preservation project is by definition an effort to sustain culture. Jewish cemetery projects in western Ukraine not only promote individual sites of heritage, but also raise awareness of Jewish heritage and history across the region through association and comparison with other Jewish burial sites. Signage, maps, and other markers can restore visual evidence of and appreciation for the multicultural past which typifies western Ukraine in any town with Jewish cemeteries and those of other faiths as well as municipal burial sites and international soldier’s cemeteries.

In the overview to exploratory essays in a Getty Conservation Institute research report on heritage conservation values, the editors observe that all contributors to the report had acknowledged that:

Activists and locals search for displaced Jewish headstones in Putiatyntsi (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast). Photos © RJH.

cultural change (and changefulness) on a global level is a reality and that the current generation is dealing with a somewhat novel set of social processes and problems. These changes are spurred by economic globalization, the spread of market ideology into ever more areas of life, demographic shifts, technological change, and identity politics — all of which call for a rethinking of the relationships among past, present, and future. … [T]here is a great deal to suggest (anecdotally, empirically, and theoretically) that in contemporary society material heritage plays an ever-greater role. (Values and Heritage Conservation: Research Report; Erica Avrami, Randall Mason, and Marta de la Torre, eds.; Getty Conservation Institute, 2000; p.14. See the references on sustainability.)

A local cultural activist clears ice from a headstone

in the Jewish cemetery of Burshtyn (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast). Photo © Victoria Matskevych.

Within this context, specific difficulties arise in western Ukraine because of traumatic wartime, postwar, and post-Soviet cultural disruptions. In the same research report, one essay focuses on:

the challenge of preserving historic centers in societies experiencing fast-paced change. This situation is commonly encountered in newly independent states, countries undergoing economic restructuring, and nations in difficult political transition. (Preserving the Historic Urban Fabric in a Context of Fast-Paced Change; Mona Serageld; Ibid.; pp.51-58.)

As noted elsewhere on this page, while Western Ukraine continues its rapid evolution since national independence, significant efforts (with limited resources) are being applied to urban development, in smaller towns as well as larger cities. A guide by the Agenda 21 for Culture program outlines myths which create conceptual challenges to strengthening the place of local cultures in sustainable development and re-humanizing settlements, and operational issues which can limit, complicate, or impede practical progress, but the text also proposes and recommends specific policies and strategies with numerous examples of successes around the world. The guide encourages further work by noting:

culture has historically been a driving force of urban development, that a variety of innovative practices to integrate cultural assets into urban development strategies are now observed throughout the world, and that “culture is now firmly recognized by the international community as a key component of strategic urban planning” […] [C]ities and towns are hubs of innovation in the economic, cultural, and social realms. (Why must culture be at the heart of sustainable urban development?; Nancy Duxbury, Jyoti Hosagrahar, and Jordi Pascual; Agenda 21 for Culture – Committee on culture of United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG); 2016. See the references on sustainability.)

Political and Social Changes

A round table in Lviv of Jewish heritage activists, city and regional political staff, religious and civil society leaders, historians, and journalists. Photo © 2017.

Political and social changes are tightly interconnected with economic and political changes in western Ukraine and beyond, and share many of the same drivers, in both long-term trends and abrupt shifts, e.g. due to WWII and the Holocaust as well as the collapse of the Soviet Union. Traditional Ukrainian society has endured repeated political changes, especially in western Ukraine’s rural villages and small towns where many Jewish burial sites are found. With the development of self-government since independence, however, younger Ukrainians especially have embraced themes of global citizenship, shared history and heritage, and responsibility, which integrate well with a rise in local volunteerism and traditional pride in place. Greater awareness of the multicultural past of a place has already prompted local residents to aid cemetery projects with the recovery of displaced Jewish headstones, and increasing social cohesion can help to diminish acts of vandalism such as graffiti at burial sites which see few visitors.

These trends appear to amplify both opportunities and expectations for cooperative projects which involve local residents and foreign Jewish descendants, sometimes with guidance and support of civil society NGOs. School teachers, local history museum directors, and small tourism leaders across the region express a desire to better connect their towns to the rest of the world, especially to people with specific links to the place. As noted, this interest comes with an expectation of ongoing, i.e. sustainable connections and two-way exchanges of communication and practical work. Not every person in every town is interested in the Jewish past of their place, of course, but travel across the region never fails to find old and young people who are curious and more. Cemetery project leaders can significantly strengthen the long-term preservation of their sites by finding and engaging these potential local stewards, and learning about their own interests and heritage for mutual benefit. See the guide page on project support for more details on this topic.

Economic Changes

The erased Jewish cemetery of Zboriv (Ternopil oblast) overbuilt with garages. See case study 19. Photo © RJH.

The “economics” of burial grounds are not calculable in the same way that values and exchanges can be determined around other parcels of land, and the “utility” and “economic opportunity” of cemeteries and mass grave sites must also be considered differently. These issues are further complicated by changes in the western Ukrainian regional economy before and after World War II, and since Ukraine’s independence. From one perspective, cemetery preservation project leaders should consider how their projects may improve or diminish the economic prospects of future generations. From another perspective, neglected burial sites without legal protections may be at risk of future official or informal expropriation and/or misuse intended to increase local incomes.

In most cases, the positive or negative economic impact of cemetery preservation projects is negligible. Clearing and landscaping a burial site in a residential area may enhance the aesthetics of the neighborhood and to a limited extent the property values. Erecting a fence or wall around the perimeter of a cemetery may close off walking paths or vehicle roads established after WWII, forcing local people to use longer paths around the site. Asserting the presence of a cemetery or mass grave through project signage, fencing, and other markers (see case study 15 on this website) may change the local perception of the site and then how the site is informally used. Communication about the presence and history of the site via digital and paper maps, websites, local history exhibitions, etc. may increase local tourism and expenditures by visitors. In reverse, an increase in tourism and visitors may place additional burdens on the site and the local community for maintenance, cleaning, information resources, etc.

The old Jewish cemetery of Chortkiv (Ternopil oblast), a site of ongoing dispute.

Bing satellite image © Microsoft and Maxar.

In the years since WWII, many prewar Jewish cemeteries have been used to anchor utility poles (for power and communications), and some have had water or sewer access points installed; most of these official municipal or regional administrative changes are physically small, if invasive, unsightly, and rather permanent. Jewish cemeteries have been informally expropriated for animal grazing and penning, for kitchen gardens, for shallow-root agricultural crops, and for planting and harvesting fruit trees. Most of this informal economic exploitation ceases when cemeteries are regularly cared for, and most of the changes are easily reversed, although the former users then either lose the supplemental income or must find alternative land.

Serious risk to cemetery preservation comes when a burial site is situated in or near a developing commercial or industrial area, and the grounds gain potential value as a building site. Surveys of Jewish cemeteries in western Ukraine display a significant percentage which were overbuilt during the Soviet era (along with some Christian cemeteries in the region). As the Ukrainian national and regional economies gradually improve, more land is considered valuable and viable for building and other transformative uses, and the pressure on “disused” land increases. Cemeteries are legally protected by Ukrainian national law, but few historic Jewish cemeteries are legally registered, so current protections are based on local religious and social traditions and on the actions of municipalities, which are also compelled to plan and promote urban renewal and local businesses. The value of burial sites as both local cultural heritage and environmental “green spaces” can be used to promote the relatively small economic value of a preserved cemetery while the surrounding area develops in other ways. The complicated legal process of registering a cemetery is the best sustainable preservation action a project can take against economic pressures; see the guide page on site surveys for more information.

Environmental Changes

Managing invasive (and poisonous) giant hogweed near a mass grave in Rohatyn (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast). Photo © RJH.

Impacts in the environmental dimension include relatively steady influences (e.g. the composition of the regional atmosphere, including pollutants), plus cyclic daily and seasonal variations (solar irradiance, wind, rainfall, vegetation growth and decay, snowfall, ice formation), plus longer-trend impacts such as the regional effects of climate change. Wild (and some domestic) animals are present at every Jewish cemetery and mass grave in western Ukraine, especially as insects, but rarely do these creatures significantly influence burial site management, even over the long term. Variations to both low and high extremes of these measures matter to site management, e.g. a lack of seasonal rainfall can be as important to site changes as an excess of it.

The most visibly significant short-term effect of the environment on cemeteries and mass graves in the region is the wild growth of native and invasive vegetation. Images of seasonal and annual grass, shrub, vine, and tree growth on this page illustrate the effect with associated time scales. Elsewhere on this website, guidance, references and tool information, plus case studies discuss managing wild vegetation in detail.

The references page on sustainability planning also provides articles on heritage at risk from climate change, and a video about preparing historic cemeteries to withstand disasters, including extreme weather events.

Technological Changes

Wikimedia Commons file data page for a photo of the Jewish cemetery of Berezhany (Ternopil oblast).

Evolution and revolution in technology may seem an unlikely opportunity or risk for the preservation of cemeteries, but recent technological changes in communication, design, instrumentation, materials, and databases have already had significant effects (mostly positive) on public awareness of Jewish burial sites, the ability of project volunteers to engage local and international civic leaders and elevate project funding, and practical efforts to rehabilitate and commemorate cemeteries and mass graves.

The guide page for communication on this website outlines some of the many ways that the explosion in popular communication media has created opportunities for cemetery project leaders, and represents perhaps the single most important current impact of technological change (see also case study 16 for a specific project example). Coupled with advances in cloud-based data and website archiving, such as the free Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, which extend the availability of information even when the originators cease to exist, burial site research and documentation efforts are now sustainable beyond initial publication. However, a cautionary note on how the advances in technology can be used both to support and undermine communication about history and heritage appears in an essay by the director of the USHMM, where she reminds that “Hitler was eager to use the latest technologies – most crucially radio, perhaps the smartphone of its day — to advance his message.” (The Lessons of History and Social Media; Sara J. Bloomfield; US Holocaust Memorial Museum; Medium; web page, 2020.)

Headstones repaired and reset by HFPJC (Avoyseinu) in the Jewish cemetery of Rozdil (Lviv oblast). Photo © RJH.

Changes in technology are continuously improving a variety of burial site survey methods on the ground, from the air, and (through instrumentation) below ground as well. Mobile and web technologies are now being used to attract visitors to Jewish burial sites and to enhance the experience of physical and virtual tourists. Research and development in allied heritage fields have produced new materials to aid and prolong conservation efforts for stone and other historic features, but may likewise introduce new environmental challenges through site contamination and other effects. Expanding academic, government, and crowd-sourced databases bring curated knowledge of local native and introduced plants and animals, headstone epitaphs and symbolism, and other relevant information directly to cemetery project researchers. Tool development enables more cemetery clearing work to be done by fewer volunteers, but string wear in modern brushcutters can create microplastic pollution at the site (unlike traditional scythes). Computing advances and cost reductions give volunteers on “shoestring” projects access to powerful design tools and image processing to create models for signs, memorials, fences and walls, and more.

Given past and current trends, it is reasonable and even likely that technological change will continue to accelerate in coming years, and that activists both in western Ukraine and abroad will be able to take advantage of new and enhanced technologies to better preserve and promote Jewish burial sites.

The Long-Term Impact of Preservation Projects: Thinking of the Project as a Dynamic Process

The Jewish cemetery of Zolotyi Potik (Ternopil oblast), site of several formal and informal projects in recent decades. Photo © RJH.

An essential sustainability consideration for heritage activists is the long-term impact of cemetery preservation projects on the burial site itself but even more so on all of the communities which depend on the site as an element of their identity and environment: local, religious, family, etc. Recognizing that project work, the site, and the interrelationships between the site and its communities and neighborhoods are not static, project concepts should evaluate not only the positive effects of proposed interventions over years and decades, but negative effects as well, and include the perspectives of all stakeholders – especially those of local citizens who will likely be future stewards of the site even if they are not currently engaged. Every cemetery project uses materials and creates waste, changes the dynamic of local ecosystems and social systems, and alters how cemetery neighbors and visitors view the site and each other. Projects are conceived and conducted to produce these changes, intended for broad benefit but sometimes having unintended adverse impacts also. The theme of this web page is meant to extend consideration of those changes and impacts well into the future.

Many Jewish cemeteries in western Ukraine were established centuries ago and were cared for by generations of local Jewish communities, then were damaged and neglected, and some now have new and small but diverse communities of caretakers. We hope this means that these cemeteries can continue to play a dynamic role in creating identity and a sense of place for people for centuries more.

Culture is best framed as a process, not as a set of objects; heritage and other cultural expressions are not static artifacts, … but are created and continually recreated by social relationships, processes, and negotiations involving actors from all parts of a society (not just conservation professionals). (Values and Heritage Conservation: Research Report; Ibid.; p.14.)

Ongoing project work at the large Jewish cemetery in Kremenets (Ternopil oblast): a view before project work in 2016 (left, via Bagnówka);

during fencing and clearing work in 2017 (center, via ESJF); follow-up clearing work by Kremenets city maintenance staff in 2020 (right, via ESJF).