![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Introduction

Any heritage preservation project at a Jewish cemetery or mass grave site in western Ukraine needs to engage at least with local authorities and residents in some form, to ensure that the project will be received well and will gain ongoing support and care after the major work is done. Projects which are initiated locally have significant advantages in this regard, but most successful projects engage and bridge between local people and Jewish descendants abroad as well as other stakeholders and interested civil society activists anywhere in the world. This guide page outlines several aspects of communication strategies and tactics to increase awareness of burial site heritage projects in planning and in progress, and presents a large number of practical suggestions and realized examples which may be adaptable to other projects, or which may spark new ideas. “Communication” as it is defined here shares many tools, methods, and characteristics with “marketing” for for-profit organizations, and some guidelines for effective marketing will also serve the communication needs of Jewish burial site projects, as they do for other non-profit organizations and projects such as museums, historical sites and parks, etc. Project leaders and volunteers will find useful ideas from studying the communication efforts of a wide variety of different enterprises.

Only one case study on project communication is fully summarized on this website; that project has deployed many of the most common communication tools and media available to inform and engage. But almost every project in western Ukraine described in the case studies and elsewhere on this website uses at least a few forms of communication to support its work, and the range of methods used for similar projects across Europe is very broad.

A local historian narrates a story of the Jewish community of Rohatyn to international news media and volunteers working in the old Jewish cemetery. Photo © RJH.

Communication considerations integrate with several other guide themes on this website, beginning with how the overall project concepts are designed, detailed, and presented for review. A burial site preliminary assessment can be documented in ways which make it useful to stimulate project support and funding. Many of the communication media described on this page are digital in some way, but physical signage and the design of memorials installed at a site can each help to increase awareness and understanding in visitors.

As described on this page, bringing together each of these pieces into a comprehensive and flexible communication strategy is important to efficient and effective use of project activists’ time and resources. Other key approaches include:

- creating a public identity for the project;

- developing and promoting narratives about the site and the work;

- speaking in more than one language;

- extending project reach through external resources; and

- establishing a presence in real and virtual geographies.

Each of these approaches is described in further detail in the sections below.

Develop a Communication Strategy to Guide the Work

Although it can be important and even essential to Jewish burial site project success, communication work supports the project indirectly and is a form of management overhead, primarily in labor because direct costs of communication are usually low. Like fundraising, communication work can be a drain on project resources, especially in the time of the lead activists who often create the content for communication programs and campaigns. Few projects can afford to spend the resources necessary to support an “everything” approach to communication. To avoid creating haphazard or conflicting messages about project priorities, plans, and progress, and to keep the messaging efficient and effective, it is important to develop a communication strategy which identifies all of the ways the project can attract attention, explain the overall project purpose and goals, inspire followers and supporters, correct and suppress misinformation, and tell a robust story about the what and why of the work.

It is rare that a project openly discusses its communication strategy, but often it is possible to see the thinking behind realized websites, publications, and other project-promoting media. Case study 16 on this website walks through the variety of communication tools and approaches used by one project which aims to attract attention to all of the Jewish history and heritage of the western Ukrainian town of Rohatyn (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast), including more than just the four burial sites there. Many more media types and methods are given as examples on this page.

We don’t intend to advise how to create a communications strategy, only that a project should have a strategy in order to coordinate ideas and messages, and to apply its time and effort in ways that are most effective for its activists, followers, and intended audience. As inspiration for projects in western Ukraine, we feature here the well-coordinated communication effort of the “Lost Shtetl” project in Šeduva, Lithuania, which includes cemetery preservation as a key component, and will highlight a number of the varied communication aspects of the project. The strategy behind this effort is visible in its effectiveness.

Components of the Lost Shtetl project communication strategy are tied together on the website of the project, providing a primary gathering point for information as well as clearly-defined identity through the project name and symbolic graphical logo. The website is bilingual with mirror subdomains in Lithuanian (for the local community) and English (for international followers). Although the primary, stable website includes no news or blog feature, every page on the site links to a social media account on Facebook where project updates can be posted, and followers can interact with the project’s leaders and staff. The web page footer also gives the project’s postal and email address plus a phone number for traditional contact methods. The primary website includes an “about” page, which outlines the project goals and includes brief biographies of the main staff, both figuratively and literally putting a face on the project.

The Lost Shtetl website menu includes links to information about the major aspects of the project, including a history of the Šeduva Jewish community, photographs and documentation of the Jewish cemetery including translated headstone epitaphs and images of the ongoing preservation project, plus photographs and GPS coordinates of memorial monuments at three Holocaust mass graves as well as a database of victims’ names. Information about projects related to the Šeduva cemetery is also provided, including the development of a museum to be built nearby the cemetery.

The project has also packaged its information to interest journalists and news aggregators, in order to spread its story and progress wider than the basic reach of its own website and social media account. In the local Lithuanian press, an article about project-sponsored directional signage was presented in a specialist religious culture forum, with a link back to the Lost Shtetl website. Frequent mention of the project since 2015 in the news section of the Jewish Heritage Europe (JHE) web portal results from a cooperative information relationship between the JHE coordinator and the Lost Shtetl project manager. The project and its components also feature on several of the information and resources pages on Jewish Heritage Europe as well, including on heritage sites in Lithuania. A summary page of external media coverage of the Lost Shtetl project is included on its website to provide ready links to these sources; to date there are more than two dozen individual third-party Lithuanian, Israeli, European, and North American articles and videos.

Other media formats support the project as well. On the website’s publications page, a printable large-format 8-page booklet provides a pictorial summary of the larger project including cemetery restoration, and two accompanying maps show the Jewish burial sites on a broad topographic image as well as a high-scale street map of Šeduva featuring nearly two dozen numbered sites of Jewish history plus current and future heritage in the town. A birds-eye (aerial drone) video of the Šeduva Jewish cemetery on YouTube complements the ground-level photographs of the cemetery and the preservation project status on the website; the video appears in several of the international news articles linked on the website and in a Jewish Heritage Europe news article as well.

The cemetery is not pinned on either Google Maps or Bing Maps, but it is clearly labeled on OpenStreetMap and featured with color and symbols to indicate a Jewish site. The burial site is also discoverable via the website of Lithuania Travel, the national tourism development agency, in a pdf and web publication on Jewish cultural heritage of the country (in English only, to date). Additional tourism interest for Jewish heritage in Šeduva may be developed in the future via an application for smart phones and tablets (supported by the EEA Grants program) called Discover Jewish Lithuania; to date the app incorporates maps and information for only eight cities and towns in the country, but the data already assembled by the Lost Shtetl project would integrate well with this new program. The project bibliography alone could be very helpful for other Jewish heritage projects in development in Lithuania.

The communication strategy of the Lost Shtetl project for Jewish burial sites and other heritage in Šeduva, Lithuania incorporates features of each of the topics discussed in the sections below. The project benefits from a large and active staff and significant funding, though it is important to note that communication likely accounts for only a small fraction of project resources, as the restoration, design, and construction work at several physical sites must consume the majority of the project’s time and funding. Smaller cemetery and mass grave projects in western Ukraine need not try to exploit all elements of the communication methods and media described here, but our advice is to consider each of the elements before selecting which will most effectively and efficiently serve the project needs.

Establish and Maintain a Public Identity

It is easy to demonstrate the importance of creating and solidifying a public identity for a Jewish burial site project: if you have heard about a project anywhere in western Ukraine, it’s probably because either the project leaders have established an active public presence in person and online, or the site project has presented itself publicly. It is of course possible to do good and lasting work in Jewish heritage simply through personal contact and dialogue – an approach which works best when the project leaders come from the residential community where the burial site is located. However, to gather larger resources and support, to attract expert advice, and to bridge between descendants and the modern local community, projects benefit from a name and a persistent, discoverable presence within the site’s region and well beyond.

To establish and cultivate an effective public identity, projects can:

Adopt a clear and unique project name: A project title which simply and intuitively associates with the project focus helps others recall the name and recognize it when seen and heard, and find the project in internet browser searches even without search engine optimization and other “marketing” strategies. In some cases a name which evokes a specific story or local history may be effective for a wide audience; the Lost Shtetl project described above is one which calls to mind a past world and way of life now gone but remembered. Usually it is best to incorporate references to the locality (the place name in past or present form), the type of project (e.g. cemetery, memorial, or a broader heritage scope), and some reference to the Jewish aspect of the work, though none of these elements is essential and other possibilities can serve. It is also important to think ahead about how the project title translates into other languages.

Create and use consistent symbolism: The guide section on memorials on this website outlines a variety of potent graphical symbol elements to spark quick understanding of a project’s focus; in communication away from the burial site, the same tools can be incorporated into logos and other project “branding”. It may be sufficient, especially as projects are getting organized, to simply use the project title as the logo, with a consistent and clear font and color scheme. Some Jewish heritage project logos shown here incorporate symbolic images such as a broken menorah and flame (for the Lost Shtetl project described above), a matzevah and Star of David (for the US/Polish cemetery project of The Matzevah Foundation), a hand supporting a Star of David (for the Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland), a deer head and Star of David (for Rohatyn Jewish Heritage; the deer is Rohatyn’s city emblem and also a carved symbol on one of the project’s recovered headstones), and an “OK” check mark to represent volunteerism in the Lviv Volunteer Center. Each of these logos is presented in consistent colors, including for the project title text.

Simple graphical logos for five Jewish heritage organizations active in Ukraine, Poland, and Lithuania.

A portion of the project page on the website of the Bolechow Jewish Heritage Society (BJHS),

activists working in Bolekhiv (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast).

Invest in a standalone website: Creating a public website for the project is a low-cost, fairly easy way to establish identity, communicate project plans and status, present permanent but updatable information, post news reports and calls for support, and more. The costs and complexity of launching and maintaining a website diminish every year; typical costs with large web-hosting companies currently range between US$50 and US$100 per year for the website including management support (software updates, security, and backups), and a domain name (the URL of the website) can be leased for US$20 or less per year. Most web-hosting services steeply discount the costs for the first year, so it’s possible to trial the process and its benefits before making a significant investment. The costs are recurring, so projects need to set aside the money each year, but a website is typically one of the least expensive elements of project management yet can give significant benefits.

Most burial site project leaders have little experience building websites, but choosing a web hosting option which includes a content management system (CMS) such as WordPress (which powers more than a third of website on the internet, and is typically free with managed hosting services) greatly simplifies website and webpage building with templates and editing tools. Formatting webpages with a CMS is comparable to a very basic word processor, mostly using preset layouts and inserting text and media. Although the page formatting options are limited, there are thousands of free and low-cost “themes” to style a website (many of which are compatible with laptop, tablet, and mobile phone screens) and other useful layout and functional features can be added through free or low-cost plug-ins. This website, its appearance, interactivity, media management, and data tables are an example of a very low-cost managed WordPress hosting package built slowly over time.

It may be tempting to start a web publishing account on a free blogging site (e.g. Blogger, Wix, WordPress.com); typically these accounts appear as subdomains on the blogging site (e.g. username.wixsite.com/siteaddress), so visitors do not see a standalone domain name, and some include advertisements on hosted pages, among other limitations. In some cases free accounts can be migrated to standard websites with unique domain names by paying a premium account fee. Unless the communication strategy for a burial site project foresees only news/blogging posts for project updates and information, it’s likely most projects will benefit from starting and continuing with a standard web hosting service.

Different tactics to bring visitors to a website are discussed in a section further down on this page, but there are also methods to enhance discoverability of the website which can be implemented on the site itself. There is a significant internet industry for search engine optimization (SEO) which generally aims to increase web traffic to commercial websites, but some of the same tools can be employed for non-profit heritage purposes as well. Some tools may be available from the project website’s hosting service, while others can be manually applied. Free evaluation of a website’s visibility is often a first step offered by fee-based SEO companies; one example is Alexa website traffic ranking by Amazon. Non-profit heritage projects are not well understood by these automated tools, so some seeding of the rankings and comparisons are necessary, and project leaders and volunteers should pay less attention to calculated ranking than to the tools proposed to expand website reach.

Photographing and note-taking for social media and blog posts about the Jewish headstone recovery project in Radekhiv (Lviv oblast). Photo © RJH.

Build a social media presence: Anyone who already uses social networking services (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and many others) to share personal observations and life events with friends knows that interacting on even just one of the various platforms can consume a significant amount of time. When tended regularly, however, the platforms can inform and engage more quickly, broadly, and powerfully than a static website, and are demonstrably useful “marketing” tools. Sharing posts from the project page into several or many groups on the network can dramatically extend the reach of individual news releases, and is one of the most important benefits of these platforms; many social groups have been organized for purposes which are oblique to the focus of the heritage project, but may be open to and even interested in overlapping concerns. Social media features are especially well-tuned to dynamic and interactive communication, which can significantly benefit several aspects of projects: event announcements, calls for volunteers and donations, status updates, and more. Brief text notes with photos and/or video are particularly effective on the larger social media platforms. When combined with hyperlinks to a stable website for context and more information, the transience of social media posts can work to stimulate and sustain interest without overloading followers, and the messaging tools which accompany most social networks allow followers to ask questions and share information of their own. Crafting compelling posts on the different platforms takes practice, but again the fluid nature of social media communication allows for considerable trial and error. Social media accounts can be effective even without a companion standalone website, so some projects (especially those with a short planned timeline) may choose to begin with only the more transient tools, and add a website if/when a more stable web presence appears important. Web platforms for posting self-made videos about the project, such as YouTube and Vimeo, are very effective means to capture interest, extend communication reach, even raise funding; individual videos are easily linked to social media accounts and to other tools for mass communication. Jewish cemetery and mass grave preservation projects in western Ukraine are unlikely to encounter or create social media controversy, but project leaders and volunteers should be aware of potential communication pitfalls.

Create distinct and persistent contact points: Just as for a small business, heritage projects need multiple contact points for different people and organizations to communicate with them. In addition to a web URL and one or more social media accounts, there should be long-term project contact info for at least email and phone/SMS messaging. For projects which create and maintain a website, email addresses which use that website domain name are valuable for strengthening project identity, and are often included free with the web hosting account. Some alternative talk and messaging accounts are advisable as well for potential contacts who may prefer to use them; examples include Skype, WhatsApp, Viber, Zoom, and variants integrated with other social media services such as Facebook Messenger.

Other ways to reinforce project identity: Project names, logos, web addresses, and contact info can be incorporated into a so-called business card (or carte de visite), a simple and inexpensive physical way to support project identity and communication. Cards can be designed on computers or online and printed anywhere in the world. Project names and logos can of course be printed on other objects as well (e.g. t-shirts, coffee cups, coasters, and calendars; the list is almost infinite), using widely-available tools in western Ukraine and elsewhere for small business marketing.

Create Narratives (and Control Them)

Once a project has established communication channels, strategic thinking should then turn toward ways to use these channels to further the project goals. For some projects, the website, social media accounts, and other communication tools may be used simply to present expository texts, images, and/or videos which explain and promote the work. Other projects may choose to develop one or more narratives to set the project in a thematic context, and perhaps to provide an alternate perspective to a conflicted history. Narratives which can be useful in telling a story about the project may present facets of:

-

Multiple types of history and a theme of loss create a useful narrative to give context to the projects

of the Bolechow Jewish Heritage Society (BJHS) in Bolekhiv.academic history, with references to published chronologies and research documented by the project and others;

- community history, including memoirs and shared experiences about prewar and wartime civil and religious organizations, schools, businesses, resistance movements, etc.;

- personal history, e.g. names and families, as well as the motivations for some volunteers (Jewish and non-Jewish) to become involved with the project;

- obscured history, especially information and connections rediscovered after the fall of the Soviet Union;

- geographical scale, i.e. spanning local, regional, and international history and connections;

- cultural themes, including unique Jewish cultural traditions as well as shared culture with other communities such as language, foods, dress, music, and other arts;

- educational themes, for example about Jewish funerary art and symbolism, the structure and poetry of headstone epitaphs, etc.; and

- imaginative or affective motifs associated with the absence of the Jewish community, such as themes of obscurity, loss, ruin, and finality.

The “Lost Shtetl” project described above prominently employs two of these motifs in its title, and others throughout its website.

All media formats are potential means for organizing and presenting these themes, including text, photographs, other graphics, video, music/songs, device applications, and formats which integrated several of these media. Narratives function beneficially in other spaces as well, for example in traditional physical museums such as local history museums. Chronological histories of Jewish communities have been used to provide context for surviving Jewish heritage on a small scale in the Rohatyn Opillya local history museum (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast) and on a large scale in the POLIN museum of the history of Polish Jews in Warsaw, Poland. Now, narrative museums need not be physical: virtual exhibitions can attract and hold attention online, such as the visual history of the local Jewish community presented by the Jewish Museum of Oświęcim on the Google Arts & Culture platform as a way to remember the people who had lived for centuries near to the place which became the Auschwitz concentration camp; the exhibition features the oldest known matzevah in the community cemetery among other artifacts and images from before, during, and after WWII.

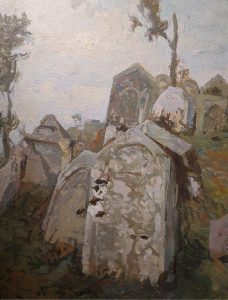

A western Ukrainian Jewish cemetery painted in the 1920s by Ivan Trush.

Image courtesy the Ivan Trush Art-Memorial Museum.

Several news articles on the Jewish Heritage Europe web portal and other sources feature interesting ways that cemeteries and burial sites in general can be brought to the attention of potential supporters and activists. One example is an artist-in-residence program at a large historic cemetery in New York City which highlights how burial grounds have inspired contemplation and original artwork for over a century. The same article features unusual narrative projects which focus on European Jewish cemeteries, including dramatic audio performances about Jewish heritage in southwest England, a multimedia project on a Sephardic cemetery in London, and visual biographies of people buried at another London Jewish cemetery. To enhance interest in the places, the projects often use terms of mystery and rediscovery.

Themes of shared culture are especially valuable in project communication as a means of connecting local non-Jewish historians, civil society activists, and residents living around Jewish burial sites to foreign Jewish descendants and heritage activists; scholars from each of these communities can help to promote common interests and share knowledge to rebuild appreciation for the area’s multicultural past. For example, the renowned Ukrainian impressionist painter Ivan Trush, much respected and beloved for his landscapes and his portraits of prominent Ukrainian leaders spanning the 19th and 20th centuries, also made a series of paintings of Jewish cemeteries from before WWI and into the 1920s, featuring sites in Berezhany, Brody, Buchach, Kosiv, and Lviv, plus unnamed others. These paintings could form the basis for a comparative exhibition with artistic photographs of the same sites today, but the possibilities are much broader.

For many projects, theirs will be the only “voice” communicating about the cemetery or mass grave, at least with any continuity and persistence. This is a small burden, but also a significant opportunity to control the narrative about the site and the lost Jewish community it represents. This means that the project may be in a position to encourage social bridge-building between the current and past communities for the benefit of the site and long-term relations between families descended from earlier neighbors, e.g. to adjust or correct stereotypes and false narratives about the communities, people, traditions, histories, and relations. Having a voice in any of the forums described here means also becoming visible and open to criticism there; as part of a communication strategy, the project should plan ahead for how to manage aggressive criticism and manipulation (“trolling”) from anyone – Jews included.

Embrace Languages

Jewish communities in what is now western Ukraine were always ethnic minorities in places of larger other nations, except in a handful of small towns and villages. Until the 20th century, most regional Jews spoke Yiddish and some Hebrew, but in order to coexist and do business with the larger neighbor populations many Jews became functional or fluent in the dominant local languages. Multilingualism is even more important today for Jewish heritage projects in the region. While fluency is not required, project leaders and volunteers must be prepared to bridge across the languages of the key stakeholders in the primary communication about the project, either through study or by engaging volunteer or hired interpreters and translators. Jewish cemeteries and mass graves in western Ukraine are shared heritage and responsibility; clear communication is essential, so language management is a key aspect of the project strategy.

The two largest stakeholder communities for projects in the region are local resident Ukrainians and foreign descendant Jews. Prioritizing languages for communication about cemetery projects would thus likely favor Ukrainian first (as defined by the state government, i.e. without local Galician dialects), and English second (both for the large Jewish descendant population in North America, Australia, and the UK, as well as for the modern use of English as a common global second language or lingua franca, e.g. in Israel). Candidates for additional languages in project communication include Russian (the mother tongue of a majority of the Jews resident in western Ukraine today and the primary language of large Jewish institutions in and around Kyiv, Dnipro, etc.) and modern Hebrew (the mother tongue of a significant portion of Jewish descendants of families once resident in western Ukraine). Specific characteristics of the project location or type may reorder these priorities or suggest additional languages. Ukrainian is essential for heritage work in the area, for communication with local residents and businesses as well as local and regional administrations, and to engage young people born since independence as the next generation of heritage activists.

As for all projects in spaces of shared heritage, the bridging across languages should be done with care. Even weak interpretation between languages can work well when speaking in person at the burial site, with the help of gestures and facial expressions. Photographs and drawings can often inform and explain without needing language at all. In writing, however, modern machine translation such as is available via Google Translate and other online tools still lacks nuance, and often even intelligibility; human translation by native speakers of the target language is best, especially if the translator is sensitive to the cultural concerns on both sides of the language gap.

Leverage Journalists, Aggregators, and Influencers

As is apparent from resource and news links on this page (and many other pages on this website), one of the best ways to amplify project communication and broaden reach is to leverage existing web portals, forums, projects, and platforms of traditional journalists and news aggregators as well as newer influential information resources. Websites plus searchable hosting services and online repositories which significantly overlap in focus with the burial site project plans and activities are obvious candidates for sharing project updates, images, videos, and links, but even general-purpose resources can be helpful over the long term if project information and data are categorized and searchable. A partial list of likely useful communication amplifiers includes:

- Jewish Heritage Europe – mentioned and linked numerous times here, this website is valuable to projects both for its news reporting/aggregating and for its organized information resources

- JewishGen – a two-way resource for region-specific reporting and outreach via email forums of Jewish descendants and family history researchers, as well as study to inform burial site project plans and surveys

- KehilaLinks Ukraine – a project of JewishGen, with opportunities to post cemetery and mass grave information and images as well as links to project websites for individual towns

-

Jewish Galicia and Bukovina (JGB) – western Ukrainian Jewish cemeteries are presented as part of JGB’s “Great Heritage” resource; information on the site is curated by the NGO’s staff, but the organization is open to collaborative data work

- Shtetl Routes – spanning a region which includes western Ukraine, individual towns with a historical Jewish presence are documented with histories and geographies, and an emphasis on narratives and surviving heritage, including cemeteries

- Virtual Shtetl – a documentation project of the POLIN museum in Warsaw, the geographic scope of towns encompasses greater historical Poland, including western Ukraine; coverage of places in Ukraine is weaker than in modern Poland, but the site managers welcome data, images, and other verifiable information where the database is currently empty

- other Jewish organizations with heritage interest – these can also be discovered by browsing the Jewish Heritage Europe sections on Ukraine and on cemeteries

-

Wikipedia – this resource is extensively used by individual researchers and the curious in many languages all over the world, yet is under-utilized by heritage projects: most of the encyclopedia pages on individual towns with Jewish history in western Ukraine make no mention of Jewish sites even if the pages sometimes mention prewar and wartime events affecting the Jewish community; for example, the page on Kremenets (Ternopil oblast) in English includes an extensive history of the Jewish community but neither mentions nor illustrates the vast Jewish cemetery preserved there, while the version in Ukrainian mentions but does not show a Jewish mass grave in the town and also ignores the Jewish cemetery, and the version in Hebrew likewise makes no mention of the cemetery

- Wikimedia Commons – even where no text pages describe Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine on Wikipedia, this companion resource often has searchable categories of images and other media relevant to heritage projects, and if not, the project can upload images for public discovery and reuse; for the Kremenets example above, there is a Commons category for the town, as well as one for Judaism in Kremenets, and another for the Jewish cemetery (which illustrates the burial site very well), and these categories and images appear high in internet browser searches with appropriate keywords

- other image-sharing websites – apart from Wikimedia Commons, some other popular photo- and image-sharing web services without formal cultural objectives are searchable and may bring a burial site project to the attention of different audiences; among these, Flickr is especially significant

- local journalists and bloggers – surveying the local area to learn what traditional and online news media exists can open opportunities for mutually-beneficial reporting on paper, the internet, and television

-

An interview about activism and Jewish heritage for a series on memory projects in practice, in openDemocracy, an online media site.

international journalists and bloggers – numerous foreign news organizations and individual bloggers are interested in Jewish heritage projects in places which are “off the beaten track”; research on internet news publications with focus on history and culture will surface many which may welcome unique stories for their readers/viewers

Generating interest on automated services without significant human editing and/or curating requires careful writing of object titles and descriptions plus selection of keywords to drive project information into search results. Working with active journalists, editors, and site curators requires more effort, but cooperative relationships can be formed to benefit both the news outlets/resources and cemetery and mass grave projects. This is especially true for Jewish Heritage Europe, which is the primary news and information resource supporting Jewish heritage preservation in Ukraine and across Europe, and which employs very active coordinators and editors. But it is also very true for journalists who work in the town and region where the burial site project is located, as their impact is very targeted to the people and administrations which most matter to project success.

Help Others Find Your Project (in Real and Virtual Worlds)

Directional signage to the Holocaust memorial in the Bakhiv forest (Volyn oblast) in Ukraine. Photo © Oksana Sushchuk.

Leveraging journalists and influencers as described above is an important way to strengthen the “push” of communication out from a burial site project. It is equally important to boost the discoverability of the project by people who seek or “pull” information from various platforms – in particular, people who do not already know about the cemetery or mass grave and the heritage preservation project there. Likewise, it can be as valuable to help people find the physical site in the real world, whether searching for that specific type of site (as heritage tourists, for example) or simply curious what features are nearby when visiting a locale, as it is to help people find information and representations of the place and project in the virtual world, e.g. on the internet.

Physical discovery aids can include directional and identification signage, and once at the burial site, information signage can explain the background to and details about the preservation project; see the guide page to signage on this website for more about this topic. GPS coordinates featured on the project website can lead travelers to the physical site using satellite navigation devices on mobile phones and in cars. Project websites can also feature embedded user-created maps built on web mapping services such as Google My Maps, either assembled by the heritage project (one example is for Rohatyn in Ivano-Frankivsk oblast) or by a third-party heritage project (for example, via a country-wide organization such as Jewish Heritage Lithuania). Another example created by the Tachov Archives and Museum Society (TAMUS) organization is embedded below to demonstrate how this can work on external websites.

To support fortuitous discovery of the burial site by passers-by, cemeteries and mass graves can be added to internet mapping databases for presentation on associated mapping services. The best known of these is Google Maps, however the Google database for Ukraine and several nearby countries is currently locked against edits due to sustained data vandalism in the recent past; the current Google Maps database is effectively “frozen” until Google can implement a secure and effective workaround. Fortunately, there are good alternate web mapping databases and services; one of the most useful is OpenStreetMap (OSM), which is free to use and edit and supplies the source data for many popular navigation applications and services.

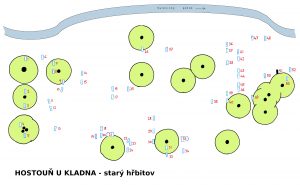

A grave map of the old Jewish cemetery in Hostouň u Kladna in the Czech Republic on the TAMUS website.

Mapping can guide visitors within a cemetery as well as direct them to it. in addition to tourism web pages and mobile applications which may provide context and deeper information than can be presented on physical signs at the burial site, detailed maps of matzevot can be drafted with links to grave data such as photographs and transliterated/translated epitaphs, as in numerous examples from cemeteries in the Czech Republic on the TAMUS website (see the map of the Písek cemetery as one example). Jewish Galicia and Bukovina (JGB) is progressing cemetery mapping work in a similar manner in western Ukraine; see case study 02 on this website for a detailed summary of their project work.

Hybrid documentation, including online digital versions of pictorial monographs on Jewish cemeteries, can capture attention and inform as well as printed versions, but with much wider audiences. One very good example is the “Neatpažinti – Neužmiršti” (Not Recognized – Not Forgotten) treatise on the Jewish cemetery in Alytus, Lithuania, with photographs, maps, bilingual text, and trilingual epitaph inscriptions of every known headstone at the site, produced through a cooperative effort of a local school, local ethnographic museum, the municipality, and the MACEVA Lithuanian Jewish Cemetery project; see a news article on Jewish Heritage Europe about the book effort published on the Issuu electronic publishing platform.

Projects with sufficient funding and/or skill can also support the development of tailored tourism applications for internet-connected tablets and smartphones; implementation may be simply the inclusion of Jewish burial sites in a local or regional heritage tourism app, or may be an app specifically to enhance tourism at one or many Jewish sites. These applications may be dedicated to mobile devices, but alternatively they can instead be written as mobile-ready websites, such as an audio walk series for Chernivtsi created by Centropa’s Trans.History project. Traditional tourism information brochures and maps still work very well, if there is sufficient local infrastructure for the development and distribution of paper maps and guides. Clever but inexpensive heritage site and project promotion can help, as in a souvenir Euro note featuring the Neolog synagogue in Lučenec, Slovakia using the design elements and colors of real Euro bank notes.

Finally, one other standard method for expanding the reach of project communication in the real world should be mentioned here: in-person presentations and lectures about the heritage and the project work often attract people who are interested to learn but may have no prior knowledge of the site and its history. Presentations with images and video by project leaders and volunteers can be especially useful at libraries, museums, high schools, and other education institutions in the town and region where the burial site is located, and can also be tailored to the interests of foreign Jewish cultural and genealogical societies, heritage preservation forums and conferences, and more.