![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Introduction

A tzedakah (charity donation) box on a headstone in the Jewish cemetery of Storozhynets (Chernivtsi oblast). Photo © Center for Jewish Art.

Nearly every project which aims to care for a Jewish cemetery or mass grave in western Ukraine requires some form of one-time or sustained support, which may include time, effort, and/or money. The support needed to implement project concepts and plans is large compared to the available human and financial assets of most heritage activists and organizations; many project leaders struggle to locate and secure the necessary resources. This issue affects both small and large cultural heritage preservation projects of all types across Ukraine. National public policy and infrastructure problems which hinder the funding of cultural heritage projects in Ukraine were outlined in a 2019 white paper which analyzed a variety of sources and models for cultural heritage project financing, including administrative budgets, grants, credits, investments, and cooperative international programs. Comparative analysis of policies and models used in other European countries highlighted successful state-level approaches which have no parallel forms in Ukraine. With few exceptions, for the foreseeable future Jewish heritage projects in Ukraine should expect to develop their own support and funding strategies.

Institutional support opportunities, both local and international, are scarce for Jewish burial site preservation in western Ukraine. Cemetery maintenance and care is of course underfunded nearly everywhere in the world, for both civil burial grounds and cemeteries of all faiths. However, the loss of nearly every regional Jewish community during the Holocaust, the large number of Jewish mass graves created during that period of terror, the comparably large number of Jewish cemeteries which were erased or destroyed under Nazi and Soviet occupations, plus the fragile Ukrainian economy since national independence, together create a Sisyphean task in western Ukraine which causes most institutions to simply walk away, and the remainder to significantly limit their offered support. Fortunately, a large number of individual local and foreign people empathize with the plight of these commemorative sites, and seek ways to help. The challenge for projects is to connect those people and the small number of active support institutions to the work.

Attracting and securing support for a Jewish cemetery or mass grave site project requires strong communication efforts to promote a site as worthy of funding or other help, to make the required applications and manage the review process, to acknowledge the help provided, and to show the work accomplished with the provided support. In many cases the project team itself should perform these communication tasks, but contracting out specialized work such as writing and managing grant applications may better serve some projects. Either way, project leaders should be prepared to do some project phase work themselves ahead of soliciting support: preliminary assessments, site surveys and desk-based research, perhaps some site clearing and cleaning, and establishing some baseline identity and communication platforms such as a website and/or a social media account.

This page and this entire website are focused on information tools and best practices for preservation of individual Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine, but some funding and support opportunities are only available to organizations which represent collections of regional sites, cross-cultural community heritage associations, and/or collegial groups of projects with a defined theme. Although not discussed here, cemetery and mass grave project leaders should also consider these association opportunities, for example the AEPJ-supported European Routes of Jewish Heritage program of cultural travel routes featuring physical heritage sites, which currently includes no regional or thematic Jewish tourism routes in Ukraine.

Project partners, volunteers, grantors, and donors thanked on a banner during a synagogue and cemetery heritage work camp. Photo © Lviv Volunteer Center.

Project support and funding opportunities are varied and multidimensional. It is difficult to clearly organize the known opportunities on a flat webpage in a way which works for all projects, but in the sections below we try to address partnerships, volunteers, grants, donations, discounts, and more, for funding, labor, materials, and services. As the focus here is primarily on support, we do not discuss loans and exchanges (either monetary or barter), and we do not discuss financial management issues (e.g. accounting or taxes). However, in the last section here we discuss the routine complications which plague funds transfers into Ukraine from foreign sources, and some transfer methods which have been successful in the recent past.

Cemetery project support is a dynamic topic which changes faster than this page can be updated: a few new institutional opportunities open every year (both within the sources listed here and from new sources) while others close, and tools for attracting small donations change even more rapidly. After reviewing the possible support sources and approaches outlined here, use links on the resources page on project support and funding, especially the news section of the Jewish Heritage Europe web portal, to research other and newer opportunities. Please contact us if you learn of additional support opportunities which we should consider for inclusion here.

Partnerships

Partnership between ESJF and the local council of Perechyn (Zakarpattia oblast). Image source: ESJF.

Partnerships between cemetery heritage activists and other organizations are among the most beneficial support strategies a Jewish cemetery project can engage in. In addition to the positive results of shared skills, tools, and resources toward a common goal, a partnership arrangement can also reduce or eliminate some common costs and risks in heritage work such as permits and legal actions. Once burial site projects are underway, project leaders may be approached by potential partners who have a shared interest in the site or who perceive a benefit to their own work, but there may well be benefit in proactively seeking out potential partners long before physical project work begins.

In many cases, partnerships need not be formal. Whether in Ukraine or outside the region, often a handshake is enough to cement an agreement on shared intent and action (if the stakes are high or the proposed actions are irreversible, of course it makes sense to solicit legal advice). Burial site project work may be outside of the official scope of some institutions, precluding formal partnerships, but even in these situations there are often ways to bridge to an informal partnership through person-to-person relations.

Some possible partners for Jewish cemetery and mass grave projects in western Ukraine include:

The village council of Zaliztsi (Ternopil oblast) partners with the local history museum and others to recover Jewish headstones and return them to the cemetery. Photo © Zaliztsi village council.

Municipalities and regional authorities: Although there are Ukrainian national laws regarding the protection of burial sites, as a practical matter the legal responsibility for care and preservation of Jewish cemeteries and heritage sites typically lies with one or more local and regional government administrative bodies. These authorities often welcome involvement and action by their citizens and interested foreigners, and some provide supplemental skilled labor to others’ projects or initiate Jewish cemetery and memorial projects on their own. Frequently the local authorities are also the best contact point for partnerships with local history and culture museums as well as tourism boards and offices, and for developing relations with cemetery neighbors and the local community, schools, journalists, and more. These local links can be critical to the long-term sustaining of burial sites. Formal and informal cooperative associations with local and regional civic authorities have already been successful in supporting Jewish burial site work at many places in western Ukraine, including Bolekhiv, Dobromyl, Kalush, Kremenets, Lviv, Nadvirna, Rohatyn, Staryi Sambir, Zalishchyky, Zaliztsi, Zbarazh, and Zolochiv. Ordinary internet searches and Wikipedia are useful to identify appropriate administration contacts for specific locations.

The research results page on execution sites in Hrymailiv (Ternopil oblast) by Yahad – In Unum.

NGOs and other civil society organizations: Several NGOs currently working with Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine and across Europe invite participation from history and heritage activists to support their work in research, preservation, and education at these sites. Key project-focused examples include Yahad – In Unum (primarily for mass graves identification and protection) and ESJF European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative (primarily for cemeteries documentation, fencing, and clearing); others with significant experience in the region include HFPJC (Avoyseinu), Geder Avos Jewish Heritage Group, Oholei Tzadikim, the Lviv Volunteer Center (LVC, a JDC-supported project of Hesed-Arieh), Jewish Galicia and Bukovina (JGB), and the Faina Petryakova Center for Judaica and Jewish Art. Cost-sharing with activist groups enables some of these NGOs to expand their work at a site or extend their work to more sites, and to accelerate protection projects.

Other civil society research and education organizations may do no physical work at burial sites, but help to promote the preservation of heritage sites and associated cultural memory through their work with databases, professional and academic researchers, and educators. Prominent examples of these organizations include Centropa and their Ukraine/Moldova project Trans.History, the Center for Urban History of East Central Europe, and the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Student work in progress in the stone conservation laboratory at Lviv Polytechnic University. Photo © RJH.

Universities, high schools, and other educational institutions: Regional universities and local schools in western Ukraine are a resource not only for knowledge, advice, and skills, but in some cases also for joint project work where the materials and issues provide educational training opportunities for their students. At the university level, classroom and field work in some specializations already include hands-on projects in site surveying, urban development and revitalization planning, landscape design, computer-aided design, stone conservation, and other studies for which a cemetery or mass grave could be an ideal subject. High schools and vocational schools need projects which teach local history and enable training in practical skills such as metalwork and horticulture. For Jewish burial site projects, Ukrainian schools at all levels welcome foreign guest lecturers speaking in their native languages as important practice for students of those languages, and often invite the speakers to choose their own topics – providing an opportunity to engage the students in cultural themes beyond language.

Beyond Ukraine, universities in Israel, the US, and especially elsewhere in Europe have already partnered with organizations in western Ukraine to further their research and hands-on work at Jewish burial sites; comparing project goals to the specific focus of university programs around the world can identify candidate partner institutions with significant skills and knowledge resources available for joint projects.

Jewish descendants of Nadvirna (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast) at the cemetery during dedication of a new memorial monument. Photo © John Capelli for the NSRG.

Jewish descendants’ groups: Heritage projects which originate locally in western Ukraine have information and contacts resources which can be hard for foreign-origin projects to acquire, but projects born in Ukraine often initially lack one of the most motivated partners – the loosely-organized groups of descendants of Jewish families who lived in the place or the area before World War II, and whose family members are buried in the cemeteries and/or local mass graves. These groups are usually formed around common interests in their family histories and a desire to recover or reconstruct memories of life before the war. Since Ukraine’s independence and its opening to tourism, many Jewish descendants have traveled to see their ancestors’ home towns and to walk the streets where Jews once lived and worked. Some have joined efforts to rehabilitate former Jewish buildings and distressed cemeteries, or to erect memorials at wartime ghettos and mass graves. The visitors also connect to other Jews from the same places, and together can create formal or informal associations for the exchange of information, funding, and volunteer labor to support projects in the region.

There are several ways to interact with Jewish descendants of specific places in western Ukraine. The largest is via a free membership account on JewishGen, a worldwide genealogy organization, and their town-focused KehilaLinks pages, their Family Finder database (which can be searched by town), and their ongoing discussion groups (more than 20,000 past messages on Galicia alone can be searched). More region-specific information and contacts can be found on Gesher Galicia, a Jewish genealogy organization with focus on western Ukraine and southeastern Poland; Gesher Galicia has its own Family Finder database which can be sorted by town, and accessed with a small annual membership fee. In addition to identifying family-interest groups and individuals, both of these organizations give free access to considerable historical and contemporary town data for many places in western Ukraine.

Volunteers for Community, Social, and Skills Service

Volunteers and leaders tour the Jewish cemetery of Chernivtsi before beginning work on an ASF-sponsored exchange project. Photo © RJH.

Jewish burial site preservation projects are nearly always led by volunteer activists working in a variety of unpaid roles while donating their time, energy, and often money. For many projects, the bulk of the skilled and unskilled labor force is also made up of frequent or occasional workers freely giving themselves in service. The “volunteer spirit” is strong around the world; people respond to calls for help in many ways. Volunteers may contribute their time and skills for a day or a year, for a finite project or to meet an ongoing need which will outlive them. Volunteering is a tremendous potential resource for Jewish cemetery and mass grave projects in western Ukraine, but one which must be developed with care to protect and nurture the heritage, the local communities, regional and national cross-cultural relations, and most importantly, the volunteers themselves.

The engagement of volunteers with Jewish cemetery projects creates impacts and benefits which extend well beyond the heritage site itself. The experience of volunteers from the local community broadens awareness of the diverse heritage and the multicultural history of the area, creating opportunities for future cooperation on long-term site care. Visiting volunteers from abroad gain from their shared effort with the local community and take home with them a deeper understanding of the unique history and future hopes of the region – information and experience they can sow further abroad.

Volunteers may join a project through organized programs or in informal walk-on roles. Examples of routes through which volunteers may join projects include:

Local citizens join foreign volunteers working in the new Jewish cemetery of Rohatyn (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast). Photo © RJH.

Local community service: Most local communities in western Ukraine provide many different opportunities for voluntary service in the area, for a wide variety of purposes. Many of the formal and informal volunteer roles are intended to improve the health and welfare of children, the elderly, and disadvantaged citizens, but beautification and care for local heritage is also a common beneficiary of community action. Often these service events are coordinated and/or sanctioned by local leaders of administrative councils, churches, schools, and the Ukrainian national “Plast” (scouting) organization. Benefits to the organizations include the development of volunteerism and leadership in the local community, civic pride and concern for public monuments and memorial spaces, and increased social cohesion and tolerance. In appreciation of shared responsibility for local heritage, Jewish cemetery project leaders and their volunteers should be prepared to join preservation work at other (non-Jewish) community sites, and work hand-in-hand with the local non-Jewish groups who have helped them to reinforce the understanding of common goals.

Local students in a youth leadership program talk with a neighbor at the old Jewish cemetery of Rohatyn (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast). Photo © RJH.

National and international youth development programs: Within Ukraine and under the oversight of the Ministry of Youth and Sports, organizations and programs focused on youth development, leadership, and mobility operate both independently and through collectives such as the National Youth Council of Ukraine (NYCUkraine), which also coordinates participation in the Eurodesk Ukraine database of service opportunities, part of an EU-managed pan-European service network. Youth development programs may include a component of volunteer service within a structure of skills training in entrepreneurship, management, and professions, and within defined network guidelines and safeguards. NGOs may join the network and propose opportunities typically for Ukrainian teenagers and under-30 adults, or they may support groups of Ukrainian young people in their application for grants and projects offered on the network by other NGOs. Browsing the database of currently-available opportunities is perhaps the best way to understand the network and how to engage with it.

The national programs for Ukrainian youth are part of a much larger network available for the development of young people across Europe, including programs for EU citizens in short- and long-term service in Ukraine. The recently-concluded Erasmus+ program is focused primarily on education, employment, and mobility, and inherited features of the earlier Youth In Action program and the European Voluntary Service (EVS) online opportunities database. Erasmus+UA has managed the program in Ukraine. A public presentation on the Erasmus+ and EVS programs in Ukraine provides a quick summary of the network and exchanges, and how they have benefited individuals and organizations which have participated. Volunteers have aided Jewish cemetery projects in western Ukraine in the past; renewal of the programs is uncertain now, but past successes suggest a similar program will be funded again.

Ukrainian, German, American, and Polish volunteers join the LVC sorting and cleaning recovered Jewish headstones at the new Jewish cemetery in Lviv. Photo © RJH.

Local, national, and foreign volunteer service programs: Other volunteer organizations sponsored by charities and foreign governments have already been effective in Jewish burial site preservation in western Ukraine, and these resources will likely continue to serve. Working primarily in the city of Lviv and in the surrounding Lviv oblast, the Lviv Volunteer Center (LVC) organizes planned events and flash-mob-style rescue actions with a variety of objectives, but always with a goal of building volunteerism in the region. In addition to health and welfare projects to support young and elderly members of the local Jewish community, each year the LVC gathers regional and foreign volunteers to work at Jewish heritage sites, including damaged or ruined synagogues, cemeteries, and mass graves, as well as city streets and buildings for the recovery of displaced Jewish headstones. In addition to large annual work camps lasting several days to a week, smaller events of a day or more are conducted several times per year to cut vegetation, clean and repair, or install signage at historic Jewish sites. The LVC trains and deploys Jewish and non-Jewish volunteers of all ages, with particular emphasis on young people, and often includes regional Jewish cultural outings in its programs.

As described below, the German Federal Foreign Office is one of several foreign government organizations which has funded volunteer work in Ukraine, including to repair, clean, and preserve Jewish cemeteries and mass grave sites. With long-term support of the Evangelical Church in Germany, the private peace organization Action Reconciliation Service for Peace (Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste e.V., ASF-eV) organizes annual two-week volunteer summer camps which send European young people to work in countries which suffered under Nazi actions in World War II, including Ukraine. Work at memorial sites is one of the core efforts of the program, and several summer camps in western Ukraine featuring volunteer work, cross-cultural exchange and education, plus music, art, and social action have already been held.

Outside of Europe, the long-term Peace Corps volunteer program of the US Department of State maintains a strong presence in Ukraine, typically with one or more volunteers serving for about two years in each oblast of western Ukraine. Although there are no formal projects to support Jewish heritage, the active volunteers in Ukraine have repeatedly demonstrated their commitment to education, community development, and cross-cultural exchange by joining work events organized by Jewish burial site project leaders and generously contributing ideas, solutions, logistical support, and hard physical labor, again and again. Trained and experienced to self-manage and to engage local people in dialogue, volunteers in the Peace Corps can be a very valuable asset to heritage projects.

Grants

A grant is a funding award typically given by a government agency or a foundation to an entity (organization or individual) without a requirement for repayment. A grant is a gift, but usually with strings attached. Individual grant funds are normally larger than those from donations (see the next section below), and are awarded after review and selection of a grant proposal or application from the recipient. Many grants for projects related to heritage require that the applicant be a legally-registered non-profit entity, but sometimes the applicant may be an educational institution (a school or museum) or a recognized individual scholar or activist. After the award, most grants also require formal funds management by the recipient in the form of regular tracking and reporting on project status and completion.

It is important to emphasize that in any year there are very few grant opportunities which could directly support Jewish cemetery or mass grave projects in western Ukraine – the number zero is most common in the recent past. Grants for the preservation and promotion of intangible cultural heritage are somewhat more available, as are opportunities for youth development, education and museum projects, NGO capacity building, and other social support functions, so it may be possible for leaders of burial site projects to advance some aspects of their work through partnerships and creative adaptation. However, project leaders should be careful to avoid seeking grants for work outside the scope of their mission, which is likely to fail in the application process and even more so if a grant is awarded.

The grant application/proposal process is usually complicated, with a number of strict requirements for content and formatting plus hard deadlines. Many project leaders and small organizations lack the skills and experience to successfully apply, or lack the time needed to complete the application and management process for long-shot funding opportunities. As a first step in considering grant opportunities, the references page for project support and funding on this website links to a free guidebook outlining the process (“The Grants Guide: A Workbook for Civic Activists“) which was written by experienced fundraisers for civil society organizations who both served as community development volunteers for the Peace Corps in western Ukraine. The references page also links to a small number of professional service organizations which can aid project leaders in locating grant announcements, assembling applications/proposals, and managing the grant through stewardship and evaluation. Internet searches and word of mouth can undoubtedly identify other professionals to help with this specialized process.

Grant opportunities come and go, and often the window of opportunity (the time between the announcement and the application deadline) is brief. For cemetery projects which can afford to invest time and/or money in grant applications, frequent searches for opportunities are recommended (see the references page for search resources), especially for smaller and one-time grants. Some established occasional grant sources include:

Ukrainian government-funded grant programs: Small grants are sometimes available from regional (oblast-level) administration budgets to support preservation of heritage. Often the departments responsible for burial sites address “questions of culture, nationality, and religion”; Jewish cemeteries and mass graves fit all three of those categories. Specific opportunities vary, and typically an application must be made to propose consideration for inclusion in future years’ budgets, as there is seldom an announced formal grant program. See the references page for some links, and/or use internet searches to locate contacts to appropriate departments.

German government-funded grant programs: The German Federal Foreign Office (Auswärtiges Amt), through laws and policies, supports diverse projects aimed at recovering and repairing what was lost or damaged by German actions in World War II. Broader support from the Foreign Office in Ukraine is also provided via capacity building and civil society priorities in the Ukraine Action Plan, such as the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), and the Foreign Office also maintains a mission in Lviv with administrative scope for all of western Ukraine (sharing responsibility for Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil, and Chernivtsi oblasts with the mission in Chernivtsi).

Some Foreign Office grants are made available to support youth development and volunteer organizations (see above). With other partners the German Federal Foreign office also financially supports a number of short-and long-term projects to recover, protect, and commemorate damaged Jewish burial sites in Ukraine resulting from Nazi killing and destruction actions. A key example is the “Protecting Memory” program (renewed in 2021 as “Connecting Memory”) now funded by the Foreign Office and jointly administered by the Foundation Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (Berlin) with the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies (Kyiv). In its pilot phase, this program provided resources and expertise to research and survey more than a dozen Jewish mass grave sites in Ukraine (including one in western Ukraine), then constructed permanent protective memorials at the sites and developed educational programs for local teachers, journalists, and museums; the next phase runs from 2021 through 2023.

Apart from large programs, the Foreign Office also sometimes provides financial support to smaller projects, such as the recovery of Jewish headstones buried under a street in Lviv in 2018.

American government-funded grant programs: Through its Public Affairs Section, the US Embassy in Ukraine (Kyiv) offers several types of grants for work in Ukraine (or between the US and Ukraine), both with and without application deadlines. The type and size of the grants varies seasonally; checking the website often is important. Embassy grant opportunities directly relevant to burial site projects are very rare, but announcements in recent years have included small grants (up to US$5000~8000 for individuals, US$15,000~25,000 for organizations) in public diplomacy (targeting media and lectures) and democracy (including civil society development and minority rights), as well as a recurring small and large grant program (US$10,000 to US$1,000,000) supported by the US Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation. In addition to the complex application process, payment through any of these grants requires registration with the US government’s System for Award Management (SAM), a difficult separate three-part process which must be frequently renewed; registration may be best left to experienced grant managers.

As noted above, the Public Affairs Section also oversees the Fulbright Program in Ukraine, a potential source of research grants which may be relevant to Jewish burial site work (including the research which led to this website). Scholarship grants are available for US citizens to work in Ukraine, and for Ukrainian citizens to work in the US, in annual competitions.

Although burial site project support would be indirect, another potential grant option is through the US Agency for International Development (USAID), which maintains a strong presence in Ukraine. Programs in civil society development and youth may offer opportunities to support local governments and citizens in their efforts to preserve community heritage of all types.

In addition to identifying and reporting on Jewish burial sites in Ukraine (and other countries), the US Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad has also funded a limited number of memorial projects at cemeteries and mass graves, including at Brody (Lviv oblast) and Berehove (Zakarpattia oblast). Projects in Ukraine are infrequent, and fundraising is often led directly by individual Commission members in their personal capacity, but the process is open to suggestions from US citizens, foreign governments, and NGOs.

Other national and international government-funded grant programs: We are currently unaware of other grant programs sponsored either through national governments (e.g. from Israel or other countries with large Jewish populations) or through international associations such as the European Union and the United Nations. In some cases there are government-sponsored and -run organizations which monitor cultural sites and fund research into best practices, but do not directly fund projects (e.g. UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites program). Ukraine’s standing outside of international unions and associations means sites in Ukraine are typically ineligible for cultural heritage and civil society funds such administered by the EEA and Norway Grants programs (and many others).

Jewish cultural foundations (and others): A foundation is an organization or trust (nonprofit, corporate, community, or private) which provides funding and/or other support to other organizations or individuals working in charitable endeavors. There are many foundations around the world organized to preserve and strengthen Jewish cultural life and heritage, though very few with the interest and capacity to support Jewish burial site preservation work in western Ukraine. Some foundations which formerly provided grants to advance a wide variety of material heritage projects now only support narrowly-defined educational projects, e.g. for Jewish museums, libraries, and archives. Others fund projects to document Jewish cemeteries (creating catalogs of matzevot) but not the physical preservation of those stones or the cemeteries in which they stand. Many charities and foundations exclusively support living Jewish communities and their physical, spiritual, and educational needs. Unfortunately, there is no known information clearinghouse for foundation grant opportunities which is searchable with unique keywords to filter for Jewish burial site project support, although searching the Jewish Heritage Europe web portal with the keyword “grant” shows a variety of past opportunities which can be researched for updates plus examples of grant-funded projects around Europe (mostly outside of Ukraine).

Despite the limitations noted above, it may still be worthwhile for some projects to review grant opportunities of known foundations with a Jewish culture focus, especially if those projects intend to do more than typical preservation work. For example, cemetery projects which are registered as nonprofits and conceived as open-air museums with plans for long-term public outreach and exchange may consider investigating one or more of several types of museum grants offered annually by the Rothschild Foundation Hanadiv Europe. Other foundations, while not directly supporting heritage projects, may provide funding to educators and academics who work on some aspects of cemetery projects.

Lists of large private and corporate foundations without a specific Jewish focus can be researched for grant opportunities which align with Jewish burial site project goals. There is no known history of an award from any of these grant sources, so the investment of time may not be worth the small chance of funding and support.

Donations

Compared to grants, donations are usually smaller, more personalized gifts and may come in the form of money, services, materials, equipment, tools, or other items of value to a Jewish burial site project. Qualification for donations is almost always less formal than for grants, though stewardship and responsiveness of the project leaders to the donors is still an important aspect of the process. Even though there are no formal application or tracking requirements, developing and implementing a fruitful donation campaign still takes time, skills, and other resources which can take project leaders away from the core work of the heritage project. For many small projects, donations will make up most or all of the unilateral contributions toward the work, though this category of support overlaps with volunteers (see above) and discounted materials and services (see the section below).

Although donations of money are often the primary support method for both donors and projects, direct in-kind donations of needed tools, building materials, etc. are sometimes more valuable, and can be a way to reduce finance-related fees, avoid perceived risks of corruption, and enhance donor satisfaction.

Sources and methods of donations are extremely varied, and some forms evolve quickly. See the references page on project support and funding for some well-known donations sources. Several of the most common sources are briefly described here, but every project should consider as wide a range of sources as possible, and renew their investigations often:

In-person: It is not uncommon for visitors to Jewish cemeteries and mass graves in western Ukraine to respond to the visible need for help by giving something of value to support ongoing work. Donors of this type may be heritage tourists, cemetery neighbors or local business owners, work camp volunteers, NGO leaders, and others. Typical donations include small amounts of cash, hand tools, decorative plants, and food and cold water for volunteer workers. Sometimes the donation may amount to the collection of waste materials, or free disposal of waste on private land. Other opportunities for in-person donations of money include speaking engagements and informal group meetings where heritage preservation concerns are discussed. These donations may not aggregate to large monetary value, but direct contact with the donors produces intangible benefits which amplify the gifts.

Jewish descendants: Groups organized of foreign Jewish descendants to discuss interlinking family histories in a particular village, town, or city in western Ukraine can be valuable partners to cemetery and mass grave preservation projects, as discussed above. Within these groups, and independent of any partnerships, individual descendants are also potential sources of donations to burial site projects of all types, as are individuals within the much larger population without direct connections to the project site. Engaging with descendants usually requires that project leaders make a reasonable case for sustained preservation work, demonstrate the capacity to successfully undertake the work, and serve as intermediaries between descendants and the workers at the site, whether contract or volunteer. The same tools useful for identifying Jewish descendants’ groups which are outlined in the partnerships section above are useful for communicating with individuals within those groups. JewishGen and other family history organizations generally do not allow their email forums to be used for soliciting funds, but sometimes make exceptions for one-time community appeals.

Crowdfunding and crowdsourcing: The expansion of internet reach and tools, and especially social networking, have significantly boosted the capability of heritage projects to raise money (via crowdfunding) and attract donations of labor, services, materials, etc. (via crowdsourcing) from their peers, i.e. individuals and small organizations. Links to several applications and forums for crowdfunding and crowdsourcing are given on the project support references page on this website, but this mode of donating is by far the most dynamic, with new applications and programs introduced each year.

A basic method for attracting donations is via simple appeals on personal or project accounts on social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and many others (these platforms are also popular in Ukraine at similar rates to the rest of the world). Facebook also has a special fundraising program with several categories applicable to Jewish cemetery projects in western Ukraine; fees are low for personal projects and zero for registered nonprofit organizations. Banking-style donation aggregators such as PayPal Money Pools and PayPal.Me are useful for time-limited or event-targeted small donation collection of any size. Some popular dedicated crowdfunding platforms are geared toward projects and charitable causes, including Indiegogo and GoFundMe as just two examples (there are dozens of smaller sites); independent versions exist as well, and larger projects may be able to organize a crowdfunding campaign on their own website. Note that many crowdfunding platforms are intended for projects to support startup businesses, cryptocurrencies, and video game development, but some platforms which are nominally geared toward developing arts projects (such as Kickstarter) have already served to support creative communication about Jewish memorial spaces.

Even the methods which do not originate on social media platforms are often best promoted there after the basic background and goals information, images and video have been set up elsewhere. Except for direct payments via free bank (or equivalent, e.g. PayPal) transfers in some countries, nearly all of these donation methods incur fees for the donor or recipient or both, especially if credit cards are involved; some of the fees are substantial, and rules can be restrictive, so project leaders should read all platform documentation carefully.

Sponsorships and corporate donations: Beyond the grant possibilities discussed in the section above, corporations sometimes make donations of new or reconditioned equipment or materials which can be used in cemetery preservation projects. In other cases, corporations may sponsor a heritage organization, agreeing to carry the cost of some portion of the project, or protective work clothing, etc. To attract sponsorship or corporate donations, project leaders must identify personal connections (through an employee or manager of the corporation) or public relations value in the work which could benefit the company. We are not aware of any examples of these kinds of donations applied to Jewish cemetery projects in western Ukraine, but potential opportunities can be identified with the manufacturers and distributors of vegetation clearing tools, building materials, and signs, as well as professional services from law firms, printers, and landscape designers.

Discounted Tools, Materials, and Services

Discounts which cover most but not all of the cost of essential project equipment or services can sometimes make an important difference in the speed and/or quality of burial site preservation work. In some cases, an institutional donor may want the recipient to pay a portion of the market price of materials, tools, software, etc. to partially offset the production and distribution costs or to demonstrate good-faith intent on the part of the project. Discounts based on fabrication costs vary significantly; software discounts (with very low production costs) tend to be very steep, while discounts for physical tools and materials are often much smaller, except when the items are returns or are older and/or discontinued models.

Many corporate discount programs require that the recipient be a registered charity or other non-profit organization in their home country; major discount opportunities exist in Ukraine, in the US, across Europe, and elsewhere. Most large computer hardware and software companies have some form of charitable giving program, but often do not directly manage these activities, instead donating the items to dedicated service companies which review applications and distribute the items on their behalf. Project leaders in need of office equipment and software suites, professional design and analysis software, and other items, should first research the software and hardware company websites to understand their program requirements, then follow the instructions to apply.

In the US and elsewhere outside Ukraine, these examples may suggest a wide variety of discount options for further research: Creation Engine; Microsoft for Nonprofits; Autodesk Technology Impact Program.

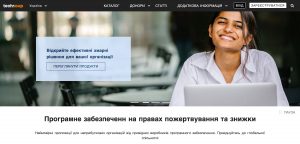

In Ukraine, TechSoup (which also has programs in the US and elsewhere on the globe) provides heavily-discounted products or licenses from Microsoft (Windows, Office suite, SQL Server, Exchange Server), Autodesk (AutoCAD plus specialty design and integration collections), Amazon Web Services, the Adobe Creative Cloud suite, and Zoom for businesses, many at only 10% of normal cost. Trimble Navigation’s competing SketchUp CAD system, which may be scaled better to small heritage projects, is available through Trimble’s non-profit discount program via partners in the US and abroad; a full-featured annual license in Ukraine costs less than US$40. Internet research can identify many other discount opportunities in Ukraine and elsewhere for specific tools and services. Opportunities for discounts from other software vendors are possible through a program at SoftProm, as well.

Transferring Project Funds into Ukraine

Carved symbol of a tzedakah box on a broken headstone in the Jewish cemetery in Karczew, Poland.

Image CC-BY-SA Nikodem Nijaki.

As anyone knows who has attempted to work on heritage projects in Ukraine and seek monetary support from foreign sources, it can be quite difficult to transfer funds across the border to Ukrainian banks and individuals. Many of the difficulties are directly or indirectly a result of significant corruption in government and banking processes in the years following Ukraine’s independence from the Soviet Union, and the national government’s ongoing efforts in recent years to impose strict transparent controls against money laundering and foreign influence. Changes in policies and processes are frequent (currently more than once per year), causing confusion among bank staffs and disrupting online transactions. However, overall the controls appear to be moving in the right direction, and for larger projects the constraints are a reasonable trade-off for increased financial security.

For Ukrainian NGOs with accounts at Ukrainian banks: International wire transfers are permitted and practical for registered NGOs holding accounts at Ukrainian banks. Ukrainian banks are converting to IBAN account numbering and SWIFT network registration; this simplifies transfers from other European countries but remains a complication for some smaller US banks. To comply with bank and government controls, wire transfers from foreign bank accounts currently must be accompanied by a signed letter from the donor which:

- identifies the donor as a private citizen or an institution, and if an institution, the purpose of the institution and the role of the letter’s author in that institution

- indicates the amount of the transfer in the currency of receipt and the receiving account number

- states the purpose of the transfer as a donation to the (named) recipient NGO

- states that the transferred funds are intended only for the non-profit activities of the NGO, according to the NGO’s statutes

- identifies the origin of the transferred funds, including both the originating foreign bank and the ultimate source (e.g. collected personal donations)

- provides contact information for the letter’s author

The NGO’s accountant or legal counsel can provide up-to-date information about current requirements. Wire transfers may also be used to directly pay registered building contractors and other materials and service companies instead of through an NGO if the recipients are known and trusted.

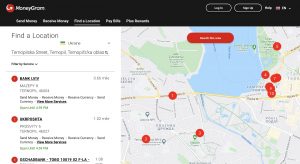

For individual project leaders and informal associations: Wire transfers incur expenses which make them inefficient for smaller donations and payments, but wires (as described above) can be used to fund local (Ukrainian) bank accounts when those costs are justified. Otherwise, low-cost interbank transfers (between “card accounts”) which are common within Ukraine do not work across the national borders, so what remains viable are cash and cash-like transfers. Examples include:

- hand-carrying cash into Ukraine to deliver to project leads or others: As of this writing, Ukraine limits cash of any currency brought into the country by citizens and visitors to a total amount equal to EU€10,000, which must be reported orally at customs entry. Amounts over EU€10,000 are possible with a written customs declaration and proof of origin from the source bank. Foreign countries also have limits and declaration rules for carrying cash out; for example, the US has no limits on outbound cash, but amounts over US$10,000 must be declared.

- cash withdrawals at Ukrainian banks using foreign bank cards: For foreigners visiting western Ukraine to support burial site preservation projects, it is possible to withdraw small amounts of cash from ATMs/cashpoints at banks in towns and cities; even with the low withdrawal limits typical of Ukrainian banks, several withdrawals can add up to a sizable donation. Generally it is better to use machines served by western European banking networks (e.g. Raiffeisen Bankengruppe) as they more commonly connect to banks in many countries and often have machine interfaces in a variety of languages. Using any of these machines normally incurs both foreign transaction fees and currency exchange fees, which can sum to 5% or more of individual withdrawals.

- person-to-person money transfer: The global financial services companies Western Union and MoneyGram both operate widely in western Ukraine, and provide simple online methods for sending donations or payments in cash almost instantly to anyone with a photo ID. Limits on cash transfers and the fees applied to each transfer are variable, but can be researched in advance. Funding these transfers via a donor’s credit card can trigger surprisingly high fees from the credit card companies, so usually it is best to fund via bank transfer or debit card. Most banks in western Ukraine are networked to one or both services, making pick-up easy for the recipient.