![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Introduction

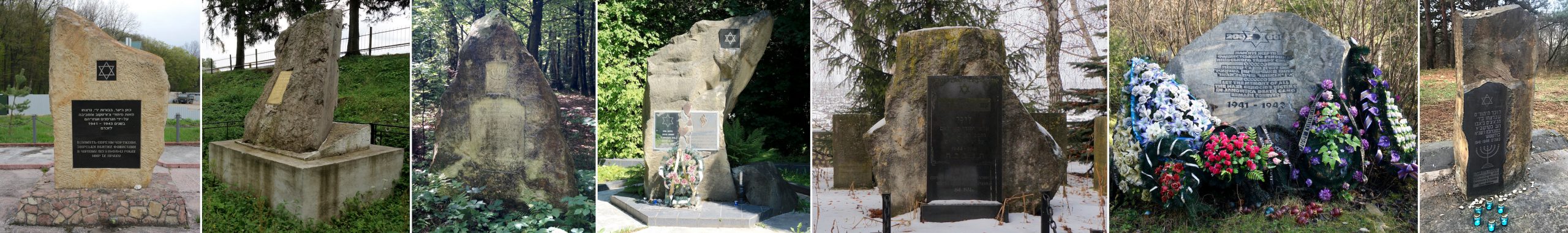

Single headstone fragments serving as memorial markers for entire Jewish cemeteries in western Ukraine:

Yavoriv old cemetery, Kamianka-Buzka old cemetery, Vybranivka. Photos © RJH.

Physical signs providing direction and site identification can indicate where Jewish burial sites are located in western Ukraine. Information signs at a site can tell some of the history of a Jewish cemetery or mass grave and the community it represents, in text and sometimes in images. Memorial monuments as discussed on this page can also locate and inform, and through their materials, forms, symbols, and inscriptions may provide alternative ways to interpret and understand a site and its meaning. New monuments typically incorporate modern materials which are assembled using current building methods commonly available in the region, so this page only briefly covers new construction and the maintenance of older post-war memorial markers. Instead, the topics here focus on the conceptual design elements available to project activists who wish to erect a monument at a cemetery or mass grave in order to commemorate an individual, a family, a Jewish community, or an event. Some activists will already have in mind the materials and art they intend to employ, the emotions they wish to evoke, and the meaning they hope to convey; the text and image galleries here may still serve as a catalog of design elements (forms and symbols) for comparison to and perhaps confirmation of the new project strategy. Additional references to support project concepts and implementation are given on the references page for monuments and a page on design tools (paper to software to physical models) on this website, and an example memorial monument project in western Ukraine is detailed with dimensions, costs, images, and more in case study 08.

Although we use the two terms memorial and monument somewhat synonymously on this page and this website, scholars note some subtle differences. Samuel D. Gruber, an expert on Jewish art and monuments, has frequently referred to extant Jewish cemeteries themselves as monuments, and observed in a recent blog post on Holocaust memorials in American synagogues:

We tend to use the terms “monument,” and “memorial” interchangeably, but the two words have different origins and shades of meaning. Every monument is some kind of memorial, but not all memorials need be monuments. “Monument” comes from the Latin verb “monere;” “to warn.” We all need warning of many dangers, from ritual impurity to fascist intolerance to genocidal annihilation. “Memorial” comes from the Latin “memoria” or memory and can have more benign and strengthening meaning.

In an important overview article on monuments and memorials in the YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, James E. Young, who wrote “The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning” and other texts on art and memory, notes:

[T]here are memorial books, memorial activities, memorial days, memorial festivals, memorial sculptures, and memorial museums. Some of these evoke mourning, some celebration. Monuments, on the other hand, refer to a subset of memorials: the material objects, sculptures, and installations used to memorialize a person, a community, or a set of events. A memorial may be a day, a conference, or a space, but it need not be a monument. A monument, on the other hand, is always a kind of memorial.

Extremes of scale: the enormous monument at the new Jewish cemetery in Kazimeierz Dolny, and memorial pebbles left by visitors at the grave of Arnošt Lustig and his family in the new Jewish cemetery in Prague. Photos © RJH.

Note also that a monument need not be “monumental” to serve its memorial purpose; massive monuments such as that installed at the new Jewish cemetery in Kazimierz Dolny, Poland are imposing and memorable themselves, but in Jewish tradition a simple pebble placed on a grave marker of any kind can signify remembrance of an individual or a community, a sign that a person, a people, and a past is not forgotten.

Although much of the information presented here could apply as well to monuments in town squares, synagogues, and other spaces even far away from burial sites, and to tangible and intangible memorials in general, our focus is on the preservation of Jewish cemeteries and mass graves in western Ukraine and thus on the physical markers which are added to these spaces to extend memory toward permanence and to enhance understanding. The sections which follow discuss how monuments influence and reinforce communal or collective memory of people and events, then briefly describe the state of existing Jewish burial site monuments in western Ukraine, before illustrating the variety of monument styles and symbols found in the region (and elsewhere in Europe) in descriptive and image formats. The page ends with a review of considerations in developing texts for inscriptions on physical monuments, and with brief information about monument construction and maintenance plus the need to consider sustainability in design for enduring memory.

The biblical commandment “Zakhor” (remember) on a monument at the Jewish cemetery and mass grave of Mostyska/Rudnyky. Photo © RJH.

The topics of memory and memorials are complex, and continue to be studied and discussed by academics and by both religious and civic leaders. Throughout this page we lean heavily on the writings of others for perspectives, analysis, and examples. We have already mentioned the YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe as a source of excellent introductory articles on these topics tailored to the region in which our own focus dwells, as well as the art and monuments blog site of Samuel D. Gruber, who covers these topics with a global scope but who has particular expertise in eastern Europe. On this website’s About page we have quoted several times from a 2005 Jewish heritage sites report for Ukraine published by the US Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad (USCPAHA), a pioneering research effort directed by Dr. Gruber to document Jewish cemeteries, mass graves, and synagogues in the country (and others); he continues to contribute to this effort on a broader scale through the International Survey of Jewish Monuments. You will see further links to his writings and photos as important resources on the references page for this topic and in many of the sections below.

On Memory, Monuments, and Meaning

A memorial at the common grave of 12 unknown Jews whose remains were found beneath a church in 2012 and interred in the new Jewish cemetery in Rohatyn (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast) in 2014. Photo © RJH.

Unlike the rest of this website, this guide page is less about preserving existing physical heritage than about preserving memory, the underlying motivation for much of the heritage project work discussed elsewhere on this site. Memory, in the form of “memory studies“, is a growing multidisciplinary research field, already large and mature enough now as a developed study vein that a history of the subject could be written in 2011. Yet, even the terminology still creates difficulties, especially at the interface between academics and lay people, including most preservation project leaders and volunteers. As an academic pursuit, the study of memory generates research, curricula, papers, books, journals, and theses for advanced degrees, and has become the focus of professional associations, societies, and centers. Memory and monuments are particularly “hot” topics now in western Ukraine and in all neighboring regions which suffered through Nazi and Soviet terrors.

Symbolic matzevot at the new Jewish cemetery in Lublin, Poland for family members whose graves were destroyed and other family who were murdered in World War II. Photo © RJH.

It is not possible to distill onto this page the large volume of prior thinking and writing on the meaning and messaging of monuments; see the references page on this website for selections from a very wide array of resources including articles, books, and websites. A majority of the available references specifically analyze Holocaust memorials at camps and major killing sites, but much of the material can be readily adapted to Jewish monuments at burial sites, and to remembering the local communities which thrived before the Holocaust. As James E. Young highlights, at the end of the 20th century museums and memorials in Israel, far more than their counterparts in Europe, “locate[d] events in a historical continuum that includes Jewish life before and after the destruction”. For a brief introduction to the complexities of these topics, monument designers and project leaders may wish to consult the web essays by Drs. Gruber and Young noted in the Introduction to this page, or Dr. Gruber’s essay on evolving perspectives of monument concepts in America, or Dr. Young’s “The Texture of Memory” (1994), or his essay “Memory and Counter-Memory” in Harvard Design Magazine (1999), or this 1994 review of the original exhibition on “The Art of Memory“; these texts are all linked on the references page.

An unmarked site in Broshniv-Osada (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast), locally named “Hell” – which could be a Jewish mass grave. Photo © RJH.

For every heritage project leader, it is crucial to think about the issues and ideas raised in these references, because the installation of a memorial monument, even a simple pillar without inscriptions or symbols, is a stimulus and makes a statement. A stimulus also usually generates some response – compassionate, indifferent, or antagonistic, and sometimes all at once – so messaging and meaning are important.

Any monument asserts something, which at a community burial site might first be “we are here” (in Jewish tradition, a burial site is past, present, and future together) or “this place is our place forever”, much like planting a flag. In the case of mass graves, which in western Ukraine frequently give no visible clue to their presence, a monument may provide the only locating sign for visitors and locals alike. Many local people in Broshniv-Osada in Ivano-Frankivsk oblast know the Jewish mass grave site there by its familiar name of “Hell” but there is no agreement about where this “Hell” actually is.

A pile of broken headstones serves as a community memorial in the Chortkiv new Jewish cemetery. Photo © RJH.

Jews are hardly unique among national and ethnoreligious groups in their cultural emphasis on memory and monuments. In an essay on post-Soviet public memory work in east-central Europe, Susan C. Pearce writes, “As memory studies researchers emphasize, it is through repeated rituals, historic objects, and story-telling about the past that a community creates its ongoing collective life and transmits the meaning of that life to the next generations.” These themes have been important in Jewish history and religious practice for more than 2500 years. As a people repeatedly compelled to displacement and itinerancy, Jewish religious readings and practices often recall that national history, focusing on exodus and arrival, and marking geographical and temporal transitions with significant and indicative monuments. In chapter 4 of the biblical Book of Joshua, following their exile and slavery in Egypt, the Israelites at last crossed the River Jordan into the Promised Land and were then commanded by Yahweh to mark the spot with 12 stones, so that “this will be a sign among you, when your children ask you in the future, ‘What are these stones to you?'” and “these stones shall be for a memorial unto the children of Israel for ever.” The passage ends with “And Joshua set up twelve stones in the middle of the Jordan… and they are there to this day.” [Joshua 4:6-9, Wikisource edition] Historians and archaeologists note that the place where the memorial was built was known as Gilgal, and that if the story is not a myth, the stone monument has likely not survived forever – perhaps a lesson for modern designers.

Separate family, community, and individual monuments in the old Jewish cemetery of Rohatyn.

Photo © RJH.

If the breadth and depth of resources on these topics is intimidating, a review of the image galleries of extant memorial monuments presented on this page may inform and refine the project objectives and specific messaging. When considering these designs and the particular elements of a new design, it may help to recognize that memory has multiple dimensions and directions; both the project team and later burial site visitors may locate themselves at different points along several axes of thought simultaneously:

- memory is personal, familial, communal, and national

- memory is local, regional, transregional, and global

- memory is political, shared, and partisan

- memory is historical and mythical

- memory is total and selective

- memory is constant and mutable

- memory is passive and productive

- memory is self-generated and borrowed

- memory is cooperative, competitive, and negotiated

One of several large sculpted concrete covers protecting common Jewish burial pits at the Drohobych forest killing site and mass grave complex, and a family memorial commemorating named individuals. Photos © RJH.

In a final chapter of his “Writing and Rewriting the Holocaust: Narrative and the Consequences of Interpretation” (1998), James E. Young examines “the activity itself of Holocaust memorialization: the simultaneous preservation and limiting of memory, the types of meaning and knowledge of events that are generated, the evolution of these meanings in time, the manner in which viewers respond to memorial reifications of memory, and the possible social and political consequences of Holocaust memorials. […] For what is remembered here necessarily depends on how it is remembered; and how these events are remembered depends in turn on the shape memorial icons now lend them. […] [As] his material forces the monument-maker away from pure representation, it also forces his vision into particular shapes and sizes – all of which determine the texture of memory.”

A monument at the north mass grave in Rohatyn serves as a focal point for commemoration of the

destroyed Jewish community there. Photo © RJH.

Decades after the Holocaust, and especially as the last survivors diminish in strength and numbers, the often-repeated phrases “Never Again” and “Never Forget” have become a spur to memorialize the victims as well as the actions and the circumstances which led to genocide in some “permanent” way. In Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi’s “Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory“, he worries that “the real danger is not so much that what happened in the past will be forgotten, as the more crucial aspect of how it happened… [I]n the world in which we live it is no longer merely a question of the decay of collective memory and the declining consciousness of the past, but of the aggressive rape of whatever memory remains, the deliberate distortion of the historical record, the invention of mythological pasts in the service of the powers of darkness”. This concern leads him to consider another perspective: “Is it possible that the antonym for ‘forgetting’ is not ‘remembering,’ but ‘justice?'”

A History of Jewish Burial Site Monuments in Western Ukraine

A lapidary pyramid of broken headstones erected in the Jewish cemetery of Łuków, Poland as a memorial in 1948, and the same monument during a visit by Israeli students in 2018. Sources: Yad Vashem and magazin.org.il.

The YIVO encyclopedia article on monuments and memorials briefly summarizes the breaks in history which permanently altered east-central Europe’s cultural complexity. Dr. Young includes cemeteries and synagogues in the range of impacted Jewish monuments, and centers the chronology on interwar Poland (which included western Ukraine) in his review of the history of Jewish monuments:

By the end of the war, it became clear that the genocide of Europe’s Jews included the near total destruction of existing monuments to Jewish life and death in Eastern Europe: both a people and its sites of memory had been destroyed.

As became tragically apparent after World War II, the German annihilation of East European Jewry during the Holocaust fundamentally turned what had been the center of flourishing Jewish European civilization into a landscape of monuments and memorials. Most signs of Jewish life were now replaced by markers of destruction, and without significant Jewish communities left in Poland and formerly Polish lands […] to care for them, many of the monuments and memorial ruins themselves were abandoned, destroyed, or assigned new, national, and political meanings by postwar regimes.

A mass grave memorial “to the 18000 victims of Fascism” near the train station in Yarmolyntsi (Khmelnytskyi oblast) as erected just after the war, and renewed in 1994. Source: Yad Vashem.

The fate of Poland’s Jewish cemeteries is also especially instructive as an illustration of how embedded such Jewish monuments and memorials are in historical times and places.

Because the destruction of Soviet Jewry by the Nazis during World War II was immediately assimilated to the official Soviet memory of what was called “The Great Patriotic War,” there were almost no memorials to specifically Jewish victims erected in the Soviet Union during the first 40 years after the war.

[T]he only explicitly Jewish memorials to be found during the postwar Soviet era came in the unofficial, often artistically crude markers in small towns and the countryside erected by the families and surviving communities of victims. These varied in form from simple concrete gravestones marking the sites of mass executions of Jews to arrangements of stones and sticks in the shapes of Stars of David. These markers usually lasted a matter of weeks or months before being removed by authorities…

A mass grave memorial in the forest near Deliatyn (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast) seen at its unveiling in newly-independent Ukraine in 1992, and during a visit 25 years later. Sources: Yad Vashem and RJH.

Only after the collapse of the Soviet Union, beginning in 1990, do we find a relative boom in Holocaust memorial installations throughout the Baltic States, Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia.

Due partly to the great influx of Western tourists after 1989, and partly to the post-communist regimes’ own need to reclaim their nations’ histories, the memorial preoccupations, design motifs, and museum exhibitions have evolved significantly beyond mere images of death and destruction to include presentations of Jewish lives and cultures that had been destroyed.

This chronology brings us to today. From cemetery surveys by ESJF European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative plus mass grave research by Yahad – In Unum, Lo Tishkach, and Rohatyn Jewish Heritage, we estimate that 28% of extant Jewish cemeteries and 15% mass grave sites in western Ukraine (Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Ternopil oblasts) currently have some form of memorial monument (not including individual pre-war matzevot standing at their original grave sites), most of them erected since Ukraine’s independence in 1991 but some from the immediate postwar period and a handful from before the war. Images and descriptions of many of those existing monuments are given in the sections which follow.

Late Soviet-era monuments to “victims of fascism” and “citizens of the city”, without mention of their Jewish identity, at two mass graves in Rohatyn and one in Dolyna. Photos © RJH.

Forms and Styles of Existing Regional Monuments

Jewish memorial monuments in western Ukraine appear in a broad range of forms (two or three dimensions, plus various shapes, configurations, arrangements, etc.) and in styles which cannot easily be divided into distinct categories, but an attempt is made here to enable comparisons and considerations for new projects. As can be seen, some monuments incorporate more than one category of style, further blurring the distinctions. Most of the monument forms illustrated here are not unique to Jewish memorials.

In many cases, the chosen form intentionally recalls one or more shapes associated with antiquity or with funerary art, implicitly or explicitly referring to memory of the past or of the dead. In particular, many postwar memorial monuments mimic Jewish grave markers, whether in the wide variety of matzevot or in other forms typically used to mark Jewish tombs. Matzevot forms evolved in western Ukraine during and since the 20th century (as seen in the new Jewish cemetery of Lviv, for example), but new memorial monuments for families and communities may draw from any period and style to link the past to the present for both local populations and international visitors.

The lapidarium continues on the back side of the monument at the new Jewish cemetery in Kazimerz Dolny, Poland. Photo © RJH.

In this section, plaques with text and symbols are not separately discussed (see the construction section at the end of this page for more information about text and languages). However, when considering the styles shown here, make note of whether the monuments include text, and if so how much. Durable monuments are typically made of materials on which it is difficult to inscribe dense passages of text, as evidenced by the brief epitaphs on prewar Jewish headstones. Thus sometimes the choice of monument form is strongly determined by the length of desired text and the number of languages in which the text should be presented. Of course, monuments can also serve their memorial purpose without presenting any text at all, simply by their form and symbols.

The examples presented here are found across western Ukraine, with both similar and different styles from outside the region (elsewhere in Ukraine, Europe, and beyond). Many new Jewish monuments installed in Europe during the past decade are recorded in the News section of the Jewish Heritage Europe portal. For images representing even broader themes and geography, see the examples and interpretations on the Public Art and Memory blog and the Jewish Art & Monuments blog by Dr. Gruber, or search for objects and images of “Jewish Funerary Art” in the Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art on the website of the Center for Jewish Art at Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

The memorial at the remote mass grave site east of Skalat combines several monument forms. Photo © RJH.

Upright Stele or Slab:

A black Holocaust memorial stele stands beside prewar headstones at the Jewish cemetery and overlooking the mass grave site in Busk, Lviv oblast. Photo © RJH.

By far the most common monument form at Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine is the stele or slab. There are several reasons for the prevalence of this form: it mimics the shape of prewar Jewish headstones in the region, so is an expected and accepted style for Jewish memorial objects; steles recall monuments erected by a variety of ancient cultures; the simple shape is relatively easy and inexpensive to specify and form in a variety of durable materials; the flat faces offer a large amount of space on which to carve an inscription of moderate length or to attach a plaque.

Steles may be simple rectangular plates, embedded in the ground like traditional headstones, or may be attached to a base of any form with pins and adhesives such as mortar to provide better long-term stability. Many monuments of this type are rounded at the top to simulate a very common feature of historical Jewish headstones, one which is so well known that it appears in simplified icons representing Jewish cemeteries on directional signage across Europe. As seen in the examples shown here, quite often the steles or their plaques are colored black, signifying mourning and absence (see the section on color as a symbol below).

Memorial steles placed at Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine: Bilshivtsi cemetery, Brody old cemetery, Kalush mass grave in cemetery, Mostyska cemetery, Ralivka mass grave. Photos © RJH.

More memorial steles placed at Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine: Peremyshliany mass grave, Rohatyn new cemetery, Skalat destroyed cemetery, Skole mass grave near cemetery, Rohatyn old cemetery, Pidhaitsi mass grave in cemetery, Uzhhorod cemetery. Photos © RJH.

Memorial steles placed at Jewish burial sites elsewhere in Ukraine and in Poland: Kamianets-Podilskyi mass grave, Demydivka cemetery, Lutsk cemetery, Trochenbrod mass grave, Tyniec mass grave. Photos © RJH.

Block:

Memorial monuments composed of solid block forms are also relatively simple to design and construct, and in most cases they also provide significant flat area on which to carve text or to attach one or more plaques or panels with inscribed text. Although they do not as readily connote timelessness and eternity as the stele which mimics prewar Jewish headstones, the visual massiveness of most block compositions implies strength, durability, and permanence of memory. Differentiating styles as stele, block, or rock is somewhat arbitrary, and these styles overlap often as evidenced by the images throughout this page.

There is no set form for block-style monuments, which may be largely flat and low to the ground, or tilted at an angle to the horizon, or generally upright like a stele but with substantial thickness. Some compositions include blocks with curved surfaces, like the memorial to the destroyed old Jewish cemetery in Vilnius shown in the Introduction above. Two other examples installed outside of western Ukraine are shown here in a stacked-block form which relates to the pyramid form described further down this page. Black-colored massive block monuments can be especially imposing; see the Velyki Mosty forest mass grave example below.

Memorial monuments composed of block forms at Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine: Velyki Mosty forest mass grave, Novyi Yarychiv mass grave, Turka mass grave in cemetery, Rohatyn northern mass grave, Brody destroyed old cemetery, Lysynychi forest mass grave, Stryi destroyed cemetery, Tovste mass grave in cemetery. Photos © RJH.

Memorial monuments composed of block forms at Jewish burial sites elsewhere in Ukraine, and in Moldova and Poland: Kamianets-Podilskyi mass grave of Hungarian Jews, Edineț mass grave in cemetery, two mass grave memorials at the Przemyśl new cemetery, Oświęcim cemetery. Photos © RJH.

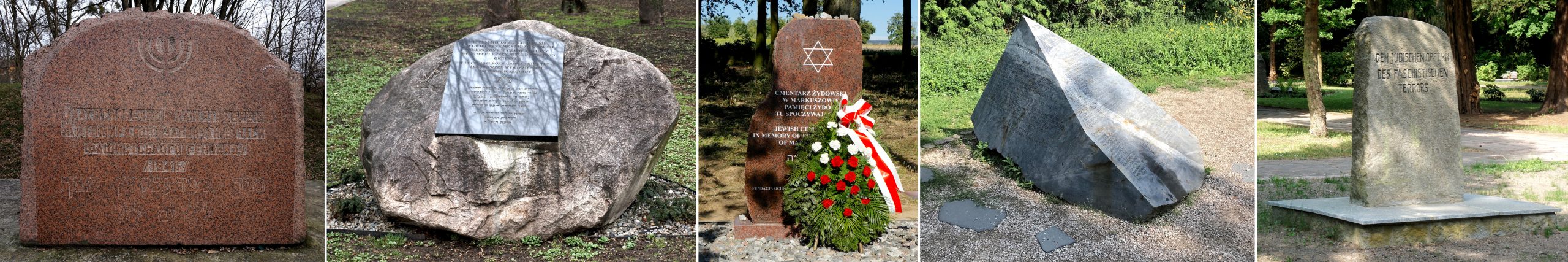

Rock or Large Stone:

A rock-form memorial monument and pathway sign at the Drohobych forest mass grave complex. Photo © RJH.

Another monument form which signifies substantiality and eternity is created from a single large rock or a grouping of large stones, typically broken from a natural stone deposit or fabricated as a composite from stone aggregate. The stone in these monuments is usually left unfinished on most or all faces, so the shape of the monument is irregular and the surfaces are rough in texture. Perhaps because of the broken appearance of the form, rock monuments are often placed at Jewish mass grave sites; the visual severity of the rough rock surface may also discourage common vandalism, as impact damage is hardly noticeable. The large size of these monuments creates sufficient space for medium-length texts describing the history of the burial site, which is most often carved into a panel which is then glued or pinned to the rock, but sometimes lettering is carved directly into a smoothed face of the rock itself. In addition to the examples in the galleries here, a rock monument commemorates the Jewish community of Nadvirna in Ivano-Frankivsk oblast and is placed at the Jewish cemetery there, as documented in case study 08 on this website.

Rock-form mass grave memorial monuments in western Ukraine: Chortkiv Black Forest, Dolyna, Ralivka forest (Sambir), Sheparivtsi (Kolomyia), Skalat, Lviv Yanovska killing site, Yavoriv forest. Photos © RJH.

Rock-form memorial monuments at mass graves and cemeteries elsewhere in Ukraine and across Europe: Zhytomyr mass grave; Jewish cemeteries in Rzeszów and Markuszów, Poland; Warsaw Miła 18 memorial and mass grave; municipal cemetery in Halberstadt, Germany. Photos © RJH.

Obelisk, Column, or Pyramid:

A monument at the mass grave near Shopky in the form of an elongated pentagonal prism,

a variant on the forms of obelisks and columns. Photo © RJH.

Several related upright geometric forms which have been used in monuments and markers around the world since antiquity now serve as stylistic signs in Jewish cemeteries in western Ukraine, both in individual gravestones since the early 20th century and in post-war memorial monuments which derive their signifying power from earlier uses. Among these shapes are the column, usually round in cross section but sometimes square or other polygons; the obelisk, a tapered column which is usually square in section and sometimes topped with a point; and the pyramid, also typically squared and with obvious reference to ancient Egypt. Other Jewish monument forms use these basic elements as components, or blend and adapt them with slight curves or other flourishes. A particularly striking example is the lapidary pyramid of broken headstones erected shortly after the war in the Jewish cemetery of Łuków, Poland, illustrated in the history section of this page above, and a similar pyramid was erected in the same period in the Jewish cemetery of Sandomierz, Poland. Another interesting and simpler adaptation was created as a lapidarium in the stylized form of an ancient ziggurat in the Jewish cemetery of Oświęcim, Poland, as seen in the gallery images here.

Upright memorial forms in western Ukraine: Boryslav mass grave, Shopky mass grave, Lviv new cemetery, Kremenets mass grave (both column/tower and obelisk/pyramid forms). Photos © RJH.

Upright memorial forms elsewhere in Ukraine and in Poland: Ostrozhets mass grave, Trochenbrod mass grave, Oświęcim cemetery, Przemyśl new cemetery, Berdychiv cemetery, Berdychiv mass grave, Kamianets-Podilskyi mass grave, Łódź new cemetery, Luchynets cemetery. Photos © Vladimir Muzychenko and RJH.

Lapidarium or Re-set Headstones:

A memorial composed as a lapidarium of broken headstones at the Jewish cemetery in Chernivtsi. Photo © RJH.

Two related monument forms use displaced and recovered Jewish headstones to reconnect the memorialized individuals with their community and its burial sites. The first of these is the lapidarium, often a “wall of memory” intended to preserve and display individual matzevot when their original grave locations are no longer known. In addition to the high, two-sided lapidarium wall at Kazimierz Dolny seen in the Introduction above, another well-known example is in the Remuh Jewish cemetery in Kraków. In most cases a lapidarium is constructed of concrete or other masonry and the headstones (usually fragmentary) are attached to the wall or other surface with mortar, pins, or hooks in a permanent location. As in some history museums, however, it is possible to protect and display the headstone fragments loosely so that they can be repositioned at a future date, perhaps even rejoined with other fragments from the same stone, as seen at Obertyn and Przysucha here as well as the memorial design for the Rohatyn old Jewish cemetery in case study 17 on this website.

An alternate use of displaced matzevot, especially when the stones are mostly intact, re-sets the stones upright as a monument which represents a cemetery through a small fraction of its lost headstones. In nearly all cases, no precise location of the corresponding original graves is known, so the re-set stones “stand in” for or signify the lost multitude, and memorialize the loss. In addition to the examples illustrated here in a gallery, a similar monument has been erected at Zaliztsi in Ternopil oblast of western Ukraine, as seen in case study 11 on this website.

The lapidarium as a cemetery memorial in western Ukraine: examples from the old Jewish cemetery in Kolomyia (now a city park) and the erased Jewish cemeteries in Dobromyl and Obertyn (with loose stones). Photos © RJH.

Jewish cemetery memorials in lapidarium form elsewhere in Ukraine and Europe: Serock, Gorlice (in construction), Ostroh, Kazimeirz Dolny cemetery, Prague (old cemetery), Warsaw (Okopowa cemetery), Przysucha (loose display). Photos © FODŻ, Gorlice Nasze Miasto, Hryhoriy Arshynov z”l, and RJH.

Re-set Jewish headstones without precise original locations as memorials for individuals and Jewish communities in western Ukraine and elsewhere. Skalat cemetery, Skalat mass grave, Hannopil cemetery, Ostroh cemetery, Łódź new cemetery. Photos © RJH and Hryhoriy Arshynov z”l.

Wall in/at Cemetery or Other Space:

A memorial wall as part of a complex of monumental signage at the mass grave near Yelykhovychi in Lviv oblast. Photo © RJH.

As noted above, often a lapidarium form of memorial employs an existing wall at a Jewish cemetery (for example at Kraków’s new Jewish cemetery on Miodowa Street), and sometimes a new wall is constructed to present recovered Jewish headstones (as at the erased Jewish cemetery of Dobromyl, Lviv oblast). However, more often walls are built or repurposed at cemeteries and mass graves in order to carry plaques for text and symbols. The prewar (and now post-war) tradition of walling Jewish cemeteries is extended to these new monuments, and walls provide the largest available space for text (and sometimes for headstone fragments) of any of the common monument forms. In some cases a memorial of this type is explicitly named a “wall of memory” and occasionally a “wailing wall” to recall the Kotel or Western Wall in Jerusalem as well as the pain which the Holocaust brought to the local Jewish community. A built wall at a mass grave site may also intentionally mark and surround a symbolic space which interprets the mass grave as a recognized cemetery, as noted below.

Memorial walls in western Ukraine: Jewish cemeteries in Sambir, Dobromyl, and Staryi Sambir, plus a Jewish mass grave near Yelykhovychi. Photos © RJH.

Memorial walls at Jewish burial sites elsewhere in Europe: Prague new cemetery, Kraków Miodowa cemetery, Odessa cemetery, Warsaw Okopowa cemetery. Photos © RJH.

Grave Form:

A monument in the form of a single grave surround at the site of the Rudne mass grave in Lviv oblast. Photo © RJH.

A number of memorials at Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine and elsewhere take the form of symbolic individual graves, or present a schematic image of a traditional cemetery either through a low form of enclosing wall or a field of markers signifying individual graves and matzevot. In some cases the forms are placed at erased prewar cemeteries, i.e. where all or nearly all original headstones were removed by occupying authorities during or after WWII, and thus the monument signifies the original purpose of the site. More often, however, memorial forms of this type are used to recall individuals, groups, and communities who were buried anonymously during the war with no markers at all, either in a mass grave following a killing event or otherwise outside of Jewish tradition, for example after so-called “natural” deaths in wartime Jewish ghettos and camps.

The simplest of these grave-like forms is an enclosure, usually in concrete or stone, reflecting either the common form of an individual grave surround (as at the Rudne mass grave site shown here) or the wall which often surrounds a prewar Jewish cemetery (as at the Rava-Ruska mass grave shown in the galleries below); in the latter case, typically the low wall also indicates the mass grave boundary as known either from eyewitness reports or later technical survey. Often upright forms are added, in the shape of a Jewish headstone, to complete the imagery of traditional prewar Jewish grave monuments.

Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine memorialized with symbolic graves and cemetery forms: Rava-Ruska mass grave, Mukachevo cemetery, Bolekhiv mass grave. Photos © RJH.

More Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine memorialized with symbolic graves and cemetery forms: Drohobych destroyed cemetery, Chernivtsi mass grave, Borove mass grave, mass grave in Uzhhorod cemetery. Photos © RJH.

A few mass grave memorials take the form of a stupa or burial mound, an ancient grave form which still serves as a recognized marker of common graves in western Ukraine for people of several ethnic groups, and may also allow the site monument to avoid disturbing a complex collection of remains.

A particularly striking version of the missing-grave monument form incorporates a matrix of even very simple markers in a grid across a field which covers anonymous graves, signifying in cemetery form that the unknown dead were individuals as well as a community. In the example from Łódź shown here, some virtual graves were further developed with traditional matzevot listing the names of persons known to be buried there (though the specific location is unknown); the large fields of simple markers are quite moving even without these personalized features.

Another missing-grave form is represented in Holocaust memorials erected at remote Jewish cemeteries, including many such monuments in Israel; often the grave contains soil or ash from the original mass grave site, as in the example shown here commemorating the lost Jewish community of Rohatyn in western Ukraine through its absence at the vast Kiryat Shaul Jewish cemetery in Israel.

Symbolic graves and cemeteries elsewhere in Ukraine and Europe: Trochenbrod mass grave; Lutsk mass grave/stupa; a destroyed cemetery in Kyiv; Dubno mass grave; Warsaw Okopowa cemetery symbolic graves; Warsaw Miła 18 mass grave mound/stupa; Lublin orphans and elderly mass grave; the Rohatyn community memorial at the Jewish cemetery in Kiryat Shaul, Israel. Photos © RJH.

Symbolic grave markers in three fields of wartime ghetto burials in the Łódź new Jewish cemetery. Photos © RJH.

Upright Sculpture:

A Soviet-era relief sculpture on a stele between mounded mass grave trenches beside the Lanivtsi new Jewish cemetery. Photo © RJH.

Although most of the monument types illustrated on this page derive their design motifs from historical and even ancient memorial styles, with a strong emphasis on architectural forms, a smaller number of extant monuments employ designs and shapes with more freely-sculpted forms, either as elements of a larger composition or as the core of the memorial. Art at sites of memory appeals to both designers and descendants as a medium which may transcend language, often helpful in western Ukraine where visitors come from a wide variety of ethnic and language groups. Two- and three-dimensional forms which interpret the Holocaust can speak directly to Jewish burial site visitors through pre-existing themes known within specific cultures, however these themes may be unknown to others and may become outmoded as “timeless” artistic conventions change, especially for figurative sculpture, even within a few decades. Project leaders for new monuments at Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine may benefit from reflecting on two large elevated memorial sculptures on the grounds of the mass grave in Dubăsari, Moldova (seen here): one is a common Soviet grouping of a soldier comforting children bringing flowers to a grave, the other is a draped female figure standing with open hands above a plaque which reads, “What for?”.

Various free-form sculptures marking Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine: Drohobych mass grave complex, Nezhukhiv mass grave, Staryi Sambir cemetery, Mukachevo cemetery, Zolochiv new cemetery. Photos © RJH.

Sculptural monuments commemorating Jewish communities and burial sites elsewhere in Ukraine and across Europe: Netishyn mass grave; Dubno mass grave; Ostroh suburb mass grave; Rivne mass grave; Slavuta mass grave; mass grave in Dubăsari, Moldova (two sculptures); Lublin Jewish orphans and elderly mass grave; Warsaw Okopowa cemetery Jewish soldiers and officers graves. Photos © Hryhoriy Arshynov z”l and RJH.

Ohel:

An ohel is built over an individual grave or a set of graves in a Jewish cemetery to signify the importance of those buried underneath. Typically the grave is already marked by an ornate matzevah, but where the matzevah is missing often a grave-covering form and a plain stele are also built when the ohel is constructed. In most cases the ohel, which may be either an open frame with a simple roof or a small closed room or set of rooms, covers the grave of a tzadik or other important Hasidic rabbi. The built structure of the ohel provides surfaces for the display of plaques or signs which identify the honored person or family. As noted in case study 14 and the experts page on this website, there are several Jewish organizations active in western Ukraine which have built ohels in the region and across east-central Europe. The images shown here are only a fraction of the extant ohels in Ukraine.

Closed and open ohels in western Ukraine: Buchach, Pechenizhyn, Rohatyn, Stratyn, Skole, Tysmenytsia, Vynohradiv. Photos © RJH.

Closed and open ohels elsewhere in Ukraine: Medzhybizh, Klevan, Mlyniv, Sataniv, Ostroh. Photos © RJH.

Other Forms:

A view from the vast Forest of the Martyrs in Israel. Photo © Visions of Travel.

Although the Jewish monument forms described and illustrated above are the most typical found in western Ukraine, many other variations are possible, including combinations of the forms above. Inspiration for new designs may come from classical or modern architecture, or from figurative or abstract art, and monuments which are erected at other sites of memory away from burial sites (in town squares and parks, for example) often may be adapted to new forms at Jewish cemeteries and mass graves. See the references to monument design and to project concepts on this website for further study on themes and forms for monument design. Galleries of acclaimed recent installations on architectural design magazine websites (as linked to the references page on landscape design on this website) can provide a broader range of examples for consideration and adaptation.

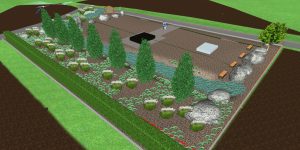

Conceptual design for a row of seven trees in a memorial at the southern Jewish mass grave in Rohatyn. Image © Green Garden.

One monument form which has gained global appreciation in recent years, though has not made an appearance in western Ukraine, is the so-called living memorial, in which non-traditional objects or even performances serve a purpose to commemorate the dead, especially victims of large-scale tragedies. For example the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City refers to itself as “a living memorial to the Holocaust” and presents programs and exhibitions on history and interpretation. Focusing on physical monuments at Jewish burial sites narrows the scope of living monuments and highlights a different form, composed not of durable inorganic materials but of “survivor trees” and other vegetation arranged to promote contemplation and commemoration in what is sometimes termed a “grove of memory”. Trees have been specially planted in North America and Europe to commemorate the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 and other 21st-century dates. Memorial trees have been incorporated into the Avenue of the Righteous at Yad Vashem since its beginning on the initiative of survivors and their descendants, and other memorials of this type have been created to foster Holocaust remembrance (for example at the Cornell Botanic Gardens in Ithaca, New York); probably the largest in the world is the Forest of the Martyrs near Ramat Raziel, Israel, which incorporates six million trees (and several large traditional monuments).

This approach is not without controversy, and unlike inert monuments a living grove or stand of trees requires local care and attention for the long term so that the memorial remains healthy and continue to serve its commemorative purpose. See the guide to burial site landscape design on this website and the related landscape references page on the topic for further information on this approach.

Jewish Symbols on Existing Regional Monuments

Symbols and color featured prominently in three community and family Holocaust memorials in a Jewish cemetery

in Sharhorod (Vinnytsia oblast). Photo © RJH.

In addition to using inscribed text and the form of a memorial monument to identify and explain the unique and common histories of Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine, monument designers frequently employ a range of symbols to communicate meaning through shared interpretation of those motifs. Some frequently-used symbols are tightly linked to Judaism, while others represent death, mourning, and the break in the life of Jewish communities created by the Holocaust.

Many of these symbols are easily interpreted by Jews and non-Jews alike, through their prior traditional use on Jewish headstones in cemeteries across Europe during the centuries before World War II. In an article on Jewish tombstones for the YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, Marcin Wodziński wrote, “The repertoire of motifs employed to decorate tombstones included ornamental architectural elements as well as perhaps 100 symbolic, figurative motifs, often tied together in stylized, complex, and very specialized compositions.” Some of the symbols on these individual memorial monuments easily extend to postwar monuments dedicated to destroyed Jewish communities at both cemeteries and mass graves, while others which are meant to call to mind the name of the deceased, their profession, or other personal characteristics are not appropriate for community memorials and are never used.

Star of David and menorah designs frequently appear together on monuments, as on this Holocaust memorial in the Jewish cemetery of Otaci, Moldova. Photo © RJH.

Although there is a kind of “canon” of common Jewish identity and memorial symbols, there are also many variants and combinations. For example, in the sections below we describe and illustrate candles and broken trees, but broken candles also appear on some monuments. Blending of symbols is also common, as is the use of multiple symbols on a single monument. A helpful pictorial selection of symbols frequently found on Jewish headstones with descriptions and analysis by Philip Trauring is found in a popular post on his informative blog site, B&F: Jewish Genealogy & More (perhaps better known by its original name, “Blood & Frogs”). Another useful catalog of symbols (in Polish language) is included on the website Cmentarze żydowskie w Polsce. A Wikipedia page in English also provides some general background (though the page in Hebrew is better illustrated), and some more detailed Wikipedia pages on individual symbols are linked below. Samuel D. Gruber frequently writes about Jewish symbolism on his several websites; for example, a post on his Jewish Art & Monuments blog site compares symbols appearing on adjacent tombs in the Jewish section of the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, France. Gruber’s Public Art and Memory web project extends his observations and analysis to broader symbol palettes and regions, illustrated with historical design drawings and his own photos.

The menorah motif appears three times (in the fence and in two monuments) at the new Jewish cemetery of Zolochiv. Photo © RJH.

Star of David:

The memorial at the Black Forest mass grave outside Chortkiv incorporates the Star of David in an emblem

on the stone and in the base which surrounds the monument. Photo © RJH.

No Jewish symbol is used more often and in greater variety in community memorial monuments at burial sites in western Ukraine than the Star of David (Magen David). The hexagram is a simple geometric design which appears in ancient decorations and architectural forms of many cultures, and appeared in Christian churches before it was documented in synagogues; it still appears as a Christmas decoration in western Ukraine today. However, since the early 19th century the star grew in popularity and importance as a cultural and political identifier of the Jewish people and a religious sign of their faith, becoming the symbol of the First Zionist Congress in 1897. Its use as a nearly exclusive Jewish sign, parallel in significance to the cross in Christianity, accelerated in the 20th century: gravestones for Jewish World War I soldiers were cut in the shape of the star; a yellow or white version was required on clothing of Jews in some cities, ghettos, and prison camps during World War II; and immediately after the war, the first, mostly personal Holocaust monuments employed the star motif fashioned from whatever materials were then available. The adoption of the star as a prominent element of the flag of the new state of Israel in 1948 has expanded current worldwide recognition of the star as a representation of Jewish people.

The star-shaped vertical lapidarium monument in front of the erased Jewish cemetery of Gorlice, Poland

as completed in 2021. Photo © Urząd Miejski w Gorlicach.

Also known as the “Shield of David”, the star device has served as a symbolic personal protector on amulets worn around the neck or wrist, and by extension can also serve this purpose to the dead and to visitors to a burial site. The use of the hexagram in the legendary Seal of Solomon amplifies the tradition which regards this symbol as a talisman for permanent installations at important sites.

In western Ukraine, the 6-point star design often appears at the top of vertical-format monuments, in cemetery fence and gate metalwork, on etched and engraved plaques, and widely as a foundation, base, or footprint of larger monuments, as seen here under large monuments at forest mass graves outside Chortkiv and Velyki Mosty. A large “floating” granite star was erected on the site of the destroyed Jewish cemetery in Piła, Poland. Even larger versions have been created for use at Jewish cemeteries, including a vertical lapidarium in front of the erased cemetery in Stróżówka near Gorlice, Poland (as reported by Jewish Heritage Europe from a Gorlice city website and a YouTube video; an image from the monument during construction is shown in the lapidarium section above), a design for a landscaped lapidarium at the old cemetery in Rohatyn, Ivano-Frankivsk oblast, a steel-encased lapidarium at the cemetery in Šeduva, Lithuania, and a living star in a monument grown from hedges at the cemetery in Rhodes, Greece.

Star designs on monuments and in gates at Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine: Velyki Mosty forest mass grave, Borove forest mass grave, Katerynivka cemetery and mass grave, Rohatyn old Jewish cemetery and south mass grave, Volove mass grave. Photos © RJH.

Star motifs in forms and ornaments at Jewish burial sites elsewhere in Ukraine and Moldova: Zhytomyr mass grave, Mohyliv Podilskyi cemetery, Sharhorod cemetery, Babyn Yar mass grave, Soroca cemetery, Rashkov mass grave. Photos © RJH.

Menorah:

An unusual depiction of a menorah upturned in ocean waves at the Jewish cemetery

in the small town of Chernivtsi (Vinnytsia oblast). Photo © RJH.

The candelabrum or menorah is a very common symbol on Jewish headstones, typically indicating the grave of a woman, and most often depicted with five arms to support candles; see the (Candle)sticks on Stone web project and blog for photo galleries and analysis of the motif. Women may also be represented on prewar headstones by the pair of candles traditionally lit by Jewish women at the opening of shabbat. Sometimes the candlesticks in these pairings may also be carved as candelabra of three or five arms instead of the more common single stick.

Menorahs also appear in and on many memorial monuments to communities, particularly at mass grave sites, as seen in photos from Bilshivtsi, Ralivka, Skole, and many others on this page. Whether marking a cemetery or a mass grave, the menorah depicted nearly always has seven arms, the same motif used today in the emblem of the state of Israel. When a single candle is depicted, this is a symbol of mourning rather than identity; see below for this usage among other less common symbols. The nine-lamp Hanukkah menorah (or hanukkiah) is never used for marking burial sites.

Common use of the seven-arm menorah motif to represent Judaism and the worldwide Jewish community is centuries old, and depiction of the menorah as a meaningful symbol to Jews dates to more than 2500 years in the past. The strong association of the Temple in Jerusalem (and its lamp) with the modern Jewish religious commemorative calendar reinforces the symbolism for Jews today, an instantly-recognizable sign which supports both identity and memory. As illustrated here from burial sites in western Ukraine, the motif is especially powerful on protective fences at Jewish cemeteries and symbolic fences as components of mass grave monuments.

Menorah designs in fencing and gates at Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine: Brody new cemetery, Obertyn erased cemetery, Rohatyn south mass grave,

Velyki Mosty forest mass grave. Photos © RJH.

Simple and stylized menorah designs at Jewish burial sites elsewhere in Ukraine and Europe: Babyn Yar mass grave complex, Dubno mass grave, Bălți mass grave,

Lublin new cemetery, Slavuta mass grave. Photos © RJH.

Break, Crack, or Gap:

A lapidarium monument with a gap, as a memorial for the erased new Jewish cemetery at Rava-Ruska. Photo © RJH.

As noted in a news report and essay posted by Samuel D. Gruber, a prominent intentional break in stone and other materials is “now an accepted Holocaust monument motif” and “represents a break in a life (like the earlier symbol of the cut-down tree), but also a break in the community, and even a break in history”. As Dr. Gruber observes, the first prominent use of this motif was probably at the huge monument at the heavily damaged new Jewish cemetery in Kazimierz Dolny, Poland (seen from the front in an image in the Introduction to this page, and from behind in the image gallery here), and the device also appears in other Holocaust-linked monuments in Europe such as at the subtle Umschlagplatz monument wall at the wartime rail loading yard of Jews from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka. Several monuments at mass graves in Ukraine, especially recent ones, combine the break or gap with the Star of David, to symbolize the break in the local Jewish community; examples have been erected recently at burial sites near Derazhne, Hrushvytsia Persha, and Matiivka, all in the Rivne oblast of Ukraine. One of the more powerful uses of this motif is at a killing site and Holocaust memorial in Athens, Greece, which takes the form of a shattered star rendered in stone.

Cracks and gaps symbolizing breaks in Jewish communities and history across Europe: Pyriatyn, Ukraine; Rajgród, Poland; Athens, Greece; Kazimierz Dolny, Poland;

Bălți, Moldova; Katerynivka, Ukraine. Photos © ESJF and Geder Avos; FODŻ; and RJH.

Color:

An unusual blue-painted headstone among many natural stone markers in the Jewish cemetery of Slavuta (Khmelnytskyi oblast). Photo © RJH.

The symbolic relationship between the color black and concepts of endings, solemnity, and mourning has been so strong since the Roman Empire and in its derivative western (European and North American) cultures that it hardly needs any explanation here. Simply browsing the gallery images on this page will show how prevalent the color is as a symbol on Jewish memorial monuments in western Ukraine and all across Europe. One professor of architecture at Lviv Polytechnic National University has proposed that monuments related to the Holocaust “should” be colored black, and the common cultural association of black with evil and violence reinforces that concept.

The 20th century saw a noticeable increase in the use of black-colored materials in individual Jewish grave markers in western Ukraine, both under the Second Polish Republic and especially under Soviet rule. Black is still favored for new burials in Jewish and other cemeteries in the region, and is easily adapted to community memorial monuments by local craftsmen.

Gold-colored paint highlights a Star of David and other features on a gate to the

Jewish mass grave east of Skalat. Photo © RJH.

Because the color white is often associated with goodness, purity, and innocence, some Jewish monuments use white to draw a visitor’s focus to the martyrs of the Holocaust and away from the perpetrators. Other neutral shades on the continuum from white to black also appear in monuments in western Ukraine, partly because of the frequent use of grey concrete as part of or entire monument forms, but also because regional limestone, sandstone, and granite is readily available in white, grey, and black. The recent practice within the Hasidic community active in Ukraine of painting the surfaces of original headstones of tzadiks in white with black lettering has contributed to a new memorial tradition as well. White materials and finishes are featured in several of the monuments illustrated in the section above, and elsewhere on this page.

The design of new memorials need not be limited to white, grey, or black, and there are examples on this page of striking monuments which wholly or partially incorporate other colors. In some cases the non-grey natural stone colors of some traditional prewar headstones are replicated in monuments to draw a symbolic connection to and an extension of historical Jewish burial practice. In other cases, monument designers have taken advantage of attractive local stone materials in shades of pink, green, and other colors to create monuments which stand out in an otherwise neutral landscape, drawing a visitor’s gaze and emphasizing the unique importance of the memorial. Rarely, and typically only as an accent, other colors associated with Jewish culture such as blue (including the historical tekhelet, a blue-violet or turquoise blue) and gold may appear on monuments. While some colors may have no specific symbolic link to Judaism, Jewish history, or the Holocaust, no colors are considered taboo on Jewish memorial monuments at cemeteries and mass graves.

Black color in memorial stele, plaque, and block forms at Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine: Busk cemetery and mass grave, Rohatyn new cemetery,

Velyki Mosty forest mass grave, Bilshivtsi cemetery, Zboriv center north mass grave. Photos © RJH.

A reference for the black color used in community memorials: black postwar grave markers in the Jewish cemeteries of Shepetivka, Khotyn, Bălți, Zhytomyr, Otaci, and at adjacent Jewish and Muslim graves in the new cemetery in Lviv. Photos © RJH.

Other Symbols:

Tree, tablet, and flame symbols at individual prewar graves in the Jewish cemetery of Chișinău, Moldova. Photos © RJH.

As noted above, there may be a hundred other traditional Jewish symbols which serve as motifs for individual or community memorial themes. Most of these other symbols have appeared on individual prewar Jewish headstones; many of the symbols are shared with other cultures. There are not a great number of these “other” symbols on memorial monuments in western Ukraine, but a few examples are shown here for consideration. A much wider variety of symbols in many different styles can be seen in well-preserved Jewish cemeteries, including the few in western Ukraine but especially the larger number in other regions; a recent tour of the surviving Jewish cemetery of Chișinău, Moldova quickly highlighted several representations of three of the symbols discussed in this section.

Tablet designs in community memorials at the Bibrka Jewish cemetery and the Tlumach new Jewish cemetery. Photos © RJH.

Broken Tree: As noted by Ruth Ellen Gruber in a photo essay for the Jewish Heritage Europe (JHE) web portal, in Jewish and many other cultural traditions, trees represent life and especially the renewal of life, while cut or broken trees symbolize death and often more specifically an early end of life. The symbol is particularly powerful as a marker for the death of a community, as from the Holocaust. The JHE photos show trees on individual matzevot but also in a striking metal monument in Budapest which takes the form of a weeping willow tree. Willow and cypress trees represent grief and mourning in many cultures, but the willow is also associated with water and thus a key source of life. A broken tree is depicted in the mass grave monument in Yarmolyntsi (Khmelnytskyi oblast) in the History section of this page, above.

Tablets: Like the Star of David, the tablets of Moses (also called the Tablets of the Law or Tablets of Stone) are a widely-recognized symbol of the Jewish people (although the legend is also important in Christianity and Islam). The paired, round-topped tablet form is associated with the Ten Commandments but more significantly with the covenant between God and the Israelites as brought by Moses, the most important prophet in Judaism. Similar to the Star of David, tablet symbols carry no meaning of mourning but stand for unique Jewish identity, community, and respect for divine justice.

Candles and Flames: Similar to but separate from the candelabrum or menorah (described and illustrated above) in appearance and symbolic meaning, another motif is the single candle or flame, representing the burning yahrzeit candle lit at home or in synagogues, typically on the anniversary on the Hebrew calendar of the death of a loved one, a widely-observed mourning tradition in Jewish life. A flame from a wax or oil lamp in monument designs also more broadly represents individual candles left at individual and community grave sites by some visitors – a tradition which is also very strong in Ukrainian Greek Catholic cemeteries in western Ukraine, and thus is recognizable in its purpose at Jewish sites by visitors from local communities as well (see the photo of the Yavoriv forest memorial above for a typical example). The image of a single candle burning is also closely associated with Holocaust remembrance, and a natural motif for related monuments.

Crosses: Although no Jewish project leader considering new monument proposals will likely include symbolic crosses among the design options, such symbols exist as markers at a small number of Jewish mass graves and erased cemeteries in western Ukraine, and likely across all of east central Europe. In the examples known to us, where the intent was to memorialize specifically Jewish victims of the Holocaust (sometimes “all victims”), the crosses were erected by local people in past decades who drew from their own religious traditions to mark and protect the sites as they knew how to do. While this effort reveals some ignorance of the symbols and traditions of local minority Jewish culture, the intent and gesture were heartfelt and positive, and in our opinion should be respected even if it is not replicated, or preserved if new durable monuments are erected.

A Note About Monument Inscriptions

Brief inscriptions in three languages at the Jewish mass grave near Ostrozhets (Rivne oblast). Photo © Vladimir Muzychenko.

The sections above discuss the use of forms and symbols on monuments at Jewish cemeteries and mass graves as means to recognize the sites, to summon memory, to signify the Jewish identity of those buried at the sites, and to provide a visible focus for an invisible past. Browsing through the images above, however, reveals a large number of monuments with text inscribed directly on the primary forms or on attached plaques. Unlike symbols, words can convey specific information about the history of the site, can pull visitors into shared experience through traditional phrases and prayers, can name the dead as individuals or communities, and can guide visualization and interpretation of the past into new forms of memory.

Individual published and unpublished memoirs (Jewish, Ukrainian, and other) of prewar and wartime life in the area around a burial site often present unverified (and sometimes unverifiable) personal histories of people, places, and events; this is an ordinary and understandable aspect of human life. Often these histories are conflicting and contested, especially between political, ethnic, and religious groups. The authors of texts inscribed on permanent physical monuments (or on separate information signage at burial sites) should strive to present factual and sourced information, and to teach truthful history, where it can be discovered and verified. No history happens in isolation, and quoting James E. Young, “[m]emory is never shaped in a vacuum”. During the many years of prewar Jewish community growth and development, and during the intense Holocaust period, the cultural heritage located at these burial sites was shared between several communities and continues to be shared today.

Monument inscriptions present powerful messages to very varied audiences, in the choice of expressions and even individual words, in factual details included and omitted, in literary and religious quotations, and even in the sequence and arrangement of the parts of the text. Care and consideration should especially be given to the languages in which the inscription will appear. Regardless of the original language in which the text is written, space and professional translation should be made so that the text can be presented in at least two languages, normally the local language (Ukrainian) and the most likely visitor languages (usually English as a majority visitor language and as a lingua franca, plus Hebrew). In some cases, Polish, Russian, or other languages may also be appropriate, e.g. at larger sites, places near current or former borders, or in communities with many speakers of those other languages. The sustainability guide also provides additional considerations which may help memorial monuments continue to serve their intended purpose for many decades. Memorial monument design and construction phases are typically very brief; when the builder walks away, the monument must speak for itself for decades to come, and to every visitor who comes to the burial site.

Three languages for site identification on one or multiple panels in western Ukraine and elsewhere: Bilshivtsi cemetery, Prague new cemetery, Rohatyn new cemetery,

Rohatyn north mass grave, Velyki Mosty forest mass grave, Yelykhovychi forest mass grave. Photos © RJH.

Lasting Memory: Construction and Maintenance of Memorial Monuments

A lapidarium monument incorporating broken headstones is built in the Ostroh Jewish cemetery with structural support

from steel-reinforced concrete. Photos © Hryhoriy Arshynov z”l.

New projects to design, construct, and maintain memorial monuments at Jewish burial sites in western Ukraine will normally incorporate modern building materials and related tools and assembly methods. In nearly all cases the feasibility of implementing a proposed design is best evaluated by local builders and municipalities (village councils, etc.), as the necessary skills and knowledge are already available in the region – as evidenced by the many examples illustrated on this page. Only in rare cases will the importing of materials and construction personnel from abroad be a workable approach. Recognized experts in heritage preservation may be able to provide some advice, but in most cases success will depend on local resources.

The Jewish mass grave memorial monuments north of Rudky (Lviv oblast) collapse and disappear into aggressive wild vegetation. Photos © RJH.

One aspect of monument development requires careful consideration before a project design is complete and construction begins: the estimated life (durability) of the monument with practical and realistic maintenance. The guide page on sustainability planning on this website (plus its associated references page) provides perspectives to consider when developing any Jewish cemetery or mass grave heritage project, and gives a number of regional examples as information and warning. Key considerations include not only the majority materials of a monument, but also the joint techniques, finishes, and a wide variety of environmental factors, including the relationship between the site, the monument, and the local community. One need only tour a number of Jewish cemeteries and mass graves in the region to understand first-hand the effects of relentless natural decay and lack of maintenance on monuments which once seemed “permanent”, even “eternal”. A good example of ongoing repair – and residual concern – is described in an essay on Jewish heritage by Samuel D. Gruber in the online Forward, including the Drohobych new cemetery and forest mass grave complex, both still requiring regular care more than a decade later and likely forever.

The lapidarium monument at the Jewish cemetery of Gorlice suspends the headstones and fragments on corrosion-resistant metal brackets. Photos © Gorlice Nasze Miasto and Urząd Miejski w Gorlicach.

In addition to natural stone (limestone, sandstone, and especially granite), many existing Jewish burial site monuments in western Ukraine employ concrete as either a foundation for other components or for the entire structure and artwork. Modern concrete is usually very durable, and can make for a long-lasting foundation, but it can be difficult to effectively repair, and as noted on the guide page to natural stone conservation and its references page on this website it can do significant chemical and mechanical harm to natural stone when the concrete is poured wet in direct contact with the stone. Likewise some metals are more suitable for long-term installation in the region’s harsh outdoor environments, and the compatibility of different metals in the continuous presence of moisture and salts should be considered when designing structural and other joints.

A hastily-assembled memorial at the Jewish cemetery in Bibrka begins to disintegrate almost immediately after completion. Photo © RJH.

Maintenance is often an afterthought in construction projects, but is far more effective if considered before construction begins and then throughout the implementation and presentation. The guide page for sustaining emphasizes the importance of engaging local community interest in shared development as a reflection of the shared history of the site, which can provide essential monitoring of the site and the condition of the monument, as well as a deterrent for casual vandalism (an ongoing risk to public art everywhere in the world). This requires budgeting and oversight, but especially communication before, during, and after the monument is designed and built. As noted above, respect for the current local community includes engagement in siting and design decisions, and also in the tone and content of any inscriptions as well as the languages in which that text is presented. As noted on the sustainability guide page, representing the history of the site as shared heritage can be one of the most important support elements for long-term care of a memorial monument.